1. A BIG IDEA IN SMALL PACKAGES: ATA Pop Homes/Leaf House

Whitehorse

The case for a tiny home really is compelling. “Who nowadays can claim that they own a home for $70,000?” proselytizes Paul Girard, owner of ATA POP Homes. “That’s the cash-down on a regular home usually! You’re using your cash-down and you live in a tiny home that’s well-built, well-designed, that’s healthy for you, healthy for the environment. You’re debt-free. It also has low maintenance and low cleaning. That’s freedom.”

If that sounds like a sales pitch, it’s because it totally is: Girard is walking around his ATA POP Homes booth at a Yukon home show in March, answering questions and touting the virtues of his high R-value, super-energy efficient buildings.

I think you could really tap into the Northern housing market, because of the cost of housing, and a lot of places are not really designed for the extreme cold. -Laird Herbert

From a 6,800-square-foot Whitehorse facility, his company builds shippable home kits in a wide range of sizes; they’ve designed them as small as 160-square-feet. Due to the level of insulation in their houses—the least efficient model is still 50 per cent more efficient than the R2000 certification suggested by the government, says Girard—and windmill and solar panel system compatibility, customers can live totally off the grid, even in the extreme cold. Girard says he’s sold five tiny homes in the last month.

“The tiny house movement is hu-MUN-gous,” he says. “Everybody is rushing on it right now.”

But what exactly is a tiny home? There isn’t an exact definition. Some say it’s a dwelling between 100 and 400 square feet. Girard says it’s anything smaller than 680 square feet, or below what a bank would usually provide a mortgage on.

According to Laird Herbert, owner of Leaf House, most tiny homes are built on car-hauler trailers—usually 8.5-feet wide by anywhere from 12 to 24 feet long.

Herbert builds tiny homes, fitted with all the amenities—shower, toilet, kitchen, bed—that you’d expect to find in a regular-sized home, and tailors them for the North. He’s done three so far and sold each of them in the Yukon. He also sells the designs of his second model online for $150 and has sold dozens of those plans across North America. “The cold climate thing is definitely an appeal for people,” he says.

To Herbert, tiny homes are a natural fit in the Arctic. “If you were strategic about it, I think you could really tap into the Northern housing market, because of the cost of housing, and a lot of places are not really designed for the extreme cold.”

There are issues with zoning because tiny homes are technically classified as an RV, he says. “To date, I think in Whitehorse, there’s been neither dissent nor assent from the city, but I really think it’s a valuable way of addressing some of the housing shortages and the cost of housing too.” Other jurisdictions have encouraged tiny house villages, he says, where a group picks up a piece of property and it becomes a quasi-RV park, but with more infrastructure. “Something like that in the Yukon and NWT could be very feasible, especially if there was a group of 10 or so that got together and bought a fair size chunk of land and could pull it off.”

“It’s a grey area that I’m sure the legislators will catch up to eventually,” he says. “But for now, there are very few rules and regulations governing how the units are built and that’s one of the reasons why I like it so much. It’s just really accessible to people.”

Herbert’s business is a part-time labour of love; he’s a little reluctant to take the plunge and make it his life, because it could take the fun out of it. “I’m sort of an anti-capitalist,” he says. “For me, it’s more about creativity and that part of it.” – H.M.

2. ALL GUSSIED UPPERS: Ashton Semple

Aklavik, NT

Hello Kitty, Monster High, Spider-Man, Air Jordan, NHL logos. Not things you would expect to see on moccasins, but beaders and seamstresses like Ashton Semple of Aklavik are learning to marry traditional styles with modern trends.

“I prefer the traditional style myself, trying to keep it alive in our culture, but I think people are wanting to learn new skills and try new things,” says Semple. Her grandmother taught her to bead her first pair of uppers—moccasin tops—when she was 16. “If my grandma felt around on my uppers and said, ‘Oh there’s one bead you never stitched down,’ I’d have to take it off and do it all over again.”

Some people sew really fast and their work ends up sloppy sometimes, and they ruin it for people that work hard on their stuff and try and sell it for a reasonable price. -Ashton Semple

Semple’s kids got her on the cartoons-and-logos track. Since she had already learned how to make bead loom pattern designs with just a traditional double needle stitch, all she had to do was look up graphed bead loom patterns online and get to work.

After sharing photos of her work on buy, sell and trade social media groups in the Beaufort Delta region, Semple says orders for both her modern and traditional works are picking up.

“People message me and ask, ‘Can you do this?’ and I’ll say, ‘I can try,’” she says. “If I don’t get it right the first time, I’ll take it off and I’ll do it again.”

Setting a fair price for her goods isn’t always easy. Beading a single upper can take up to two and a half days, but people don’t always want to pay when they can get a similar product cheaper elsewhere.

“Some people sew really fast and their work ends up sloppy sometimes, and they ruin it for people that work hard on their stuff and try and sell it for a reasonable price,” says Semple. “And then other people undersell their stuff. I think you just have to be firm on your prices.” She normally charges $180 for a pair of uppers, and most clients are willing to pay.

Now, Semple is focused on starting up a craft store in Aklavik, which will help community members access quality art supplies and serve as a place to hold workshops on traditional crafts and hide tanning.

“I’m finally trying to start a business that I wanted for how long,” she says. “It would be good, not only for myself, but for other people in the community.” – L.B.

3. HOW TO BOOST YOUR SEAL APPEAL: Nala Peter and Rannva Design

Iqaluit

Nala Peter, a full-time mom and part-time seamstress, usually sews winter outfits for her kids and sells the odd sealskin mitts and fur hats on Iqaluit’s Sell/Swap Facebook page. Except that one time, about eight months ago, when she decided to try something more discreet: sealskin lingerie.

“It was my other half’s idea,” Peter chuckles. “I laughed at him at first. I really laughed at him. And then I thought, maybe I can try one. So I did and it came up to 320 likes on Sell/Swap and over 100 comments.”

Since then she’s had a few orders for intimate items, but she admits things are still slow going. It takes her around eight to 10 hours to cut, measure and sew the sealskin lingerie, but her prices are fairly reasonable: $150-$175 for a bra and $180-$220 for a corset. She’s just making the lingerie part-time for now, but Peter hopes to open up her own webpage soon.

Peter isn’t the only Iqalummiuq experimenting with sealskin. Rannva Simonsen has been working with furs in Iqaluit since 1999, making high-end sealskin mittens, coats and hats that sell worldwide. She’s also made a sealskin bikini, skirts and even hot-pants--—“the hottest pants in the world,” Simonsen declares.

Simonsen, who plans on moving her store to downtown Iqaluit this summer from the suburb of Apex where she currently resides, hopes to revive the sealskin industry in Nunavut by making unconventional designs. (She also makes sealskin clothing for men, including stylish coats and even bow-ties.) “I like to do stunning things for people, so they think, ‘Oh sealskin is not just sealskin, it’s gorgeous.’”

As it stands, Simonsen has to buy some skins from Newfoundland, but she’s hoping the government helps develop the Nunavut sealskin economy so she can eventually buy all her skins from local hunters.

“I think it’s a great gift to have this kind of resource here, that we should be proud of and take advantage of and strut,” she says. “That’s right: strut.” – D.C.

4. THERE'S A MAP FOR THAT: SikSik app

Iqaluit

Finding your way around Iqaluit can get confusing. “For anyone who has visited here or lived here for any length of time, the houses are not organized in any logical fashion,” says Casey Lessard, a local reporter and developer of the SikSik utility app, designed to create order out of chaos. Homes and buildings are generally referred to by their number, assigned to buildings in the order they were erected. “Sometimes the numbers are in a totally different area than where you would expect, especially in the 400-series, which contains the 1600-series. And the 500s: I have a 500 beside me and yet the rest of the 500s are about half a kilometre away.”

For every 100 businesses, there’s probably only 10 real websites and only a handful of those actually do anything valuable. -Casey Lessard

Lessard, a first-time app-maker, compiled and entered all of Iqaluit’s building numbers onto a Google map grid, thus creating SikSik. The app lets users punch in a house number and find a direct route there, giving them a simple way to navigate the city’s byzantine layout. (It also provides the local weather.)

Lessard says the app is targeted at visitors, newcomers and transient workers. But he still uses it probably once a week and it’s worked to his advantage, letting him get to homes faster than other Iqalummiut to snag items advertised on the city’s Sell/Swap Facebook page.

For now, the app is free to download on both Apple and Android phones—BlackBerry users can give it a go at siksik.ca. And Iqaluit’s business owners can list their enterprise free of charge too. That’s because Lessard’s working to build up the user base—he’s got around 400 users right now and has 1,000 as a goal—and get the app translated into French and Inuktitut, as he brainstorms ways to monetize the site. Eventually he’d like to provide expandable business listings and even help bring some of the city’s many businesses online, potentially with the app providing that introduction. “I think you’ll find that for every 100 businesses, there’s probably only 10 real websites and only a handful of those actually do anything valuable,” says Lessard, “whereas a lot of them could be doing e-commerce.” – H.M.

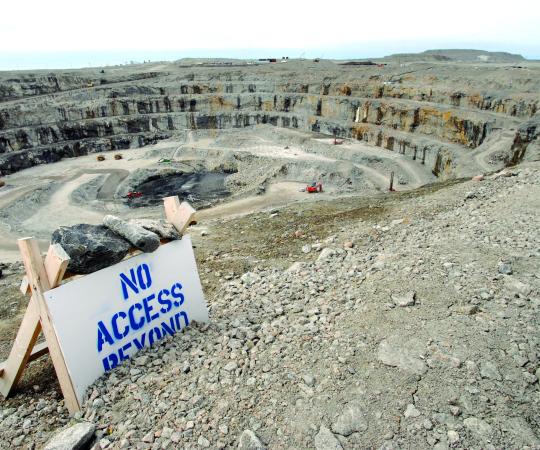

5. CHICKEN POOP FOR THE SOIL: Choice North Poultry Farms

Hay River, NT

Could chicken poop help remediate old NWT mine sites? Hay River’s Kevin Wallington thinks so. He’s the sales and marketing manager for Choice North Poultry Farms—proprietor of Polar Eggs, the territory’s only egg farm. They’ve been serving up fresh eggs from their more than 100,000 hens to hungry Northerners since December 2012. But with all those hens comes what the industry terms “by-product”—what most of us would call chicken poop. Nine tons of it. Every day. “In essence,” says Wallington, “we have a dump truck load of manure daily.”

It’ll look and smell like soil. There’s no smell left of chicken manure. -Kim Rapati

Polar Eggs has been trying to figure out what to do with the waste ever since the company started producing it. Recently, they partnered with Ecology North’s Kim Rapati, who studied mixing the manure with paper waste from the town of Hay River. Right now, paper waste takes up about 26 per cent of the town’s landfill, and a chicken poop composting facility could remove up to 14,000 square metres of material from the landfill annually.

“Compared to what it would cost us if we just left it there, and had to manage it for X number of years, to be able to properly compost this and be able to sell it, I definitely think this is a good opportunity for business,” Wallington says. “It’ll look and smell like soil,” says Rapati. “There’s no smell left of chicken manure.”

They plan on selling the compost to communities across the North that have little access to soil for use in community gardens or greenhouses, as well as commercial or industrial groups remediating the many abandoned mine sites dotting the NWT. “It’s good at helping break down any toxins or heavy metals in soil,” Rapati explains.

But the company has a ways to go yet. They’ve run into problems trying to acquire land for the project, mainly because the newly-devolved territory doesn’t have an agricultural policy and kept refusing their applications on that basis. But Wallington is hopeful they’ll get permission to clear land just one kilometre from their current site this summer, and partner with the town of Hay River to start managing the waste in the fall.“There’s all kinds of different challenges here from logistics to legislation,” says Wallington. “But I’m really encouraged just seeing how people in communities are stepping up to take ideas, and maybe even ideas that didn’t work once upon a time, and revisiting them again to see if the economics have changed or the political climate has changed.” – D.C.

6. LOTS ON THEIR MINDS: Cloudworks

Yellowknife

If Sam Gamble and Robert Warburton of CloudWorks—co-founders of an “adventure” capitalism company based out of Yellowknife—seem guarded about what they’re up to these days, it’s probably a good thing. It means other companies are hot on their ideas.

Unlike most developers in town, CloudWorks focuses on salvaging what’s already there. Instead of putting money into suburban sprawl, Warburton and Gamble invest in existing—even derelict—properties in the downtown core and find better uses for them.

I’m not sure what [tiny homes] will look like when they come here, but they’re going to look uniquely northern. -Robert Warburton

“Right now the big shtick in town is build build build. Gotta be new, and that’s very expensive—and very complex—to do when there’s still lots of stuff in town that can be reused in different ways,” Warburton says. “Most people see a lot downtown and think: ‘what can I build on it?’ They don’t think, ‘what can that old building be used for?’”

Founded in 2012, CloudWorks has invested in a number of projects around town, leasing, financing and repurposing properties. Lately, they’re talking about bringing the tiny house market to Yellowknife but admit it’ll be hard to find cheap, accessible land to put the homes on.

“I’m not sure what [tiny homes] will look like when they come here,” says Warburton, “but they’re going to look uniquely northern.”

CloudWorks allows for investments in projects from as low as a few hundred dollars to several thousand, giving more access to lower-income investors. Gamble says they want to work on projects they’d be “proud to tell their friends about.”

With Gamble newly on staff full-time and Warburton switching to part-time work with the GNWT so he can focus more on CloudWorks, they’re clearly cooking up something. But so far, they’re only giving us a taste of what that may be. – D.C.

7. CARE-BY-AIR PACKAGES: Arctic Buying Company

Winnipeg

As word of food insecurity in the North spreads throughout southern Canada, many are realizing that shipping goods by conventional methods is just not cutting it. This is where Arctic Buying Company comes in.

Tara Tootoo-Fotheringham’s plucky startup was originally created in response to confusion surrounding the rollout of the federal government’s Nutrition North program. Arctic Buying Company was one of the first small companies shipping food to remote communities, but it branched out when it became clear there was no way to get by on food orders alone. “We had to diversify or we wouldn’t have survived as a business,” says Tootoo-Fotheringham.

Arctic Buying Company turned four on April 1, and despite some rocky times, she’s figured out how to make it work. Now, from Ski-Doo parts to dogs—that Tootoo-Fortheringham boards at her home until their flight is ready—if you need it, they’ll get it for you.

With six employees, Arctic Buying Company maintains a warehouse in Winnipeg. Though it originally served only Tootoo-Fotheringham’s home community of Rankin Inlet, it now ships to all three Nunavut regions as well as northern Manitoba.

With relationships with northern airlines and the ability to get fresh foods onto planes quickly, they’re able to ship goods for hundreds of dollars less than, say, Canada Post. To Nunavut families, that’s a million-dollar idea. – L.B.

8. AFTER THE GOLD CRUSH: Randy Clarkson

Whitehorse

Family-run placer mines bring in $60 million annually in the Yukon. Randy Clarkson has found a way for them to make more, but he refuses to make a fortune off of it. He’s designed a makeshift rod mill that separates out gold from concentrates normally left behind by placer miners. The precious metal would otherwise be too tedious to extract manually from the concentrates and too environmentally harmful to treat with chemicals.

It’s basically a small rod mill: a tool normally used to grind up ore, but often rebuked for getting gold particles stuck inside. “Nobody ever thought, let’s use that as an advantage rather than a disadvantage,” Clarkson says. Because traditional rod mills are expensive, Clarkson used a cement mixer—modified to up the RPMs—and filled it with steel rods. The rods flatten out the malleable gold and grind other minerals to dust, making it easier to separate the gold later.

During testing last summer, the tool was bringing in between five to 10 ounces of gold per day (about $5,000 profit) from materials that would normally be left behind in jars and tins at the average placer mine.

The Whitehorse inventor unveiled his device last fall and is making the plans for the tool publicly available. He’s not selling a product, he says. He already made his dime researching the device, making hourly rates off government grants. It costs about $2,500 to build one, meaning it could pay for itself in half a day. “I’ve been in this business too long,” says Clarkson. “Something this simple, they can make themselves. So why would they buy it from me?” – D.C.

9. BIN THERE, DONE THAT: Yukon Blue Bins

Whitehorse

They say nature abhors a vacuum. But a couple of Yukon entrepreneurs sure don’t: they built a private recycling business in one.

The City of Whitehorse, unlike many southern municipalities, does not offer curbside recycling—a service that’s often contracted out to companies with fees recovered through taxes. At a 2012 wedding, Fraser Lang was standing around with some family members “arm-chair-quarterbacking the way to fix every problem in the territory,” says Yukon Blue Bins manager Taylor Tiefenbach. They started asking why curbside recycling wasn’t offered in Whitehorse when it was the norm in many other places. The lightbulb went on and they began brainstorming what it would take to start a small-scale business doing just that in Whitehorse. One cube van later, Lang and Co. were going door-to-door in Riverdale, signing up customers that wanted their cans and paper and plastics hauled away every two weeks for $20. “We started small,” says Tiefenbach—within six months they had 200 subscribers in two neighbourhoods. The company added another cube van, and a third as a back-up, but were mindful to keep the service consistent as they grew their customer base and service area.

Today, the business provides the private service for all of Whitehorse’s suburban ridings—although it hasn’t expanded into its semi-rural subdivisions. Along with Tiefenbach’s full-time job, the business employs four part-time workers—“about 10 to 15 hours per week for collections,” says Tiefenbach—and it has more than 750 customers.

But it could all be coming to an end: the city’s in the process of providing the curbside service. Tiefenbach sees this as another opportunity, though—with the know-how they’ve gained since starting the business, they think they stand a good chance at winning the tender. They’re even thinking of getting into handling commercial recycling needs. “Three years ago, we wouldn’t be anywhere near it,” says Teifenbach. – H.M.

10. DON'T PUT ME IN A BOX: Cash n' Carry

Hay River, NT

Driving cheap bulkstore goods, bought in Edmonton, up to small South Slave and Deh Cho communities in a passenger bus to then resell at a discount was certainly an outside-the-box idea when Mike Sharpe, and his wife Joyce Paes, made that dream a reality last summer. Despite the long distances, the couple was able to sell high-demand items such as toilet paper for less than local retailers could.

But like most dreams, it came to an end. Sharpe says he was unable to secure a business licence in Hay River to open a storefront and he’s shut down the business that was “on the way to bankrupting” him. “It was worth a try,” he says. “I really wish it would have succeeded because we would have fed so many people at the right price.”

That’s not the end of Sharpe’s dreams, though. With the equipment he racked up from Cash ‘n Carry (a passenger bus and a smaller school bus) he hopes to cash in on the huge morel boom forecast in the NWT this summer. He’ll convert the larger bus into a mushroom drier so he can package and preserve the sought-after mushrooms and later sell them for a premium online or to local buyers, rather than at a much cheaper price along the side of the road. He’ll spend his summer camping in the smaller bus. “We’re entrepreneurs up here,” says Sharpe. “We’re adaptable, we move with the times.”

Has he ever picked, dried, packed, sold and shipped morel mushrooms before?

“No, but I never did a [grocery store] on wheels before either,” he says. “Why not?” – H.M.