June 2 was a cool and cloudy day in Vancouver, and David Suda, CEO of Gold Terra Resource Corp., spent most of it on telephone calls and Zoom conferences from his home workspace. That was good news. Gold Terra, a junior mining firm exploring for gold on a nearly 800-square-kilometre land package around Yellowknife, had put out a press release that morning. In it, the company announced its intention to launch a drill program on the so-called Campbell Shear, the most prolific zone of Gold Terra’s camp. The news, landing after weeks of rising gold prices, prompted a steady stream of calls from potential investors, fund managers and analysts looking to flesh out details and learn what the news meant for the project in the bigger picture. “In some ways, we probably underestimated how quickly investors would engage,” Suda says. “We’re pleasantly surprised.”

It was certainly a far cry from two and a half months earlier. In mid-March, as the full scope of the COVID-19 crisis was becoming clear, Suda and Gold Terra’s brass met to figure out what to do. Borders were closing, travel was restricted, and markets were in full-blown panic as millions of people were being laid off or told to stay home indefinitely.

For Gold Terra, immediate issues included how to preserve the company treasury and how it could develop effective marketing for its project through the crisis. Even more important, how would it communicate?

“How exactly do you pick up the phone to pitch your project to people who don’t know if they’ll see their grandparents again?” Suda asks. “Will people care about the project if they don’t know when their children will be returning to school or when they might see a head of lettuce at the grocery store again?” And even if the company succeeded on that front, management still questioned whether it should be drilling at all. Would the market even care about its results?

It was a grim reality every Northern exploration company faced—and at a particularly crucial time of the year, when these firms seek to finance, plan and mobilize their all-important summer exploration programs. Junior mining companies sell potential; they make their money by spending money. They need to drill their deposits in hopes the results will excite investors. Those investors will then fund future exploration. The end-goal: selling the company’s asset to a major mining company or seeing the company itself build a profitable mine—all the while growing the value of the company for shareholders. Without the ability to get into the field, the company loses its most essential means of generating buzz and, ultimately, money.

Fortunately for Gold Terra, its project’s proximity to Yellowknife worked to its advantage. “In April, all of a sudden it plays out that we’re able to drill when other people aren’t because we don’t have to have a camp,” Suda says. With stringent public health measures in place, crews don’t need to fly back and forth to the drill site in the closed quarters of a helicopter cabin. They can sleep in their own beds at night. “We can work within the realm of reason,” Suda continues, “so, maybe we’re luckier than some other companies.”

The same held true for other companies in the North that were able to carry on with a 2020 exploration program. Access to local infrastructure—ground transport, supply chains and staff—helped them mitigate increased costs, such as additional air charters, and avoid physical interactions with communities that may be wary of having outsiders pass through. Moreover, it gave them the ability to quickly respond to the easing of restrictions so they could plan modified programs around the new reality of COVID-19. At least in the early days, the Northern infrastructure gap appeared to play a large part in who could and couldn’t do work in a vital sector that brings jobs and millions of dollars in spending to all three territories annually.

Most firms that were able to rescue their exploration seasons had another asset in common: gold projects. Investors typically flock to the commodity in times of global uncertainty. And gold prices experienced near all-time highs in the months after the initial pandemic crash in March, meaning gold explorers enjoyed a more welcome reception in the capital markets to get their work financed.

Everybody else has been working hard to make the most of a very difficult situation.

Banyan Gold CEO Tara Christie spent this past spring coordinating a small drilling program at her company’s road-accessible Aurex-McQuesten project, 50 kilometres northeast of Mayo, Yukon. The program launched at the start of June and will amount to 1,500 metres, a step that Christie calls Phase 1 of Banyan’s summer plan. “We didn’t want to commit to spend everything in the bank before we saw what the world was going to be like out there,” she says, explaining her company’s thinking. “We think everything is going to go all right, but people thought things were all right in early March and then, by the second week, the world had changed… We don’t want to overcommit to something we’re not going to be able to deliver.”

The aim of Banyan’s program is two-fold. First, it wants to see how the market receives the results. Second, it is treating the program as an opportunity to test out its COVID procedures and determine how much those added precautions will add to drilling costs. If things go well, Banyan could move on to a Phase Two later in the summer. (Editor’s Note: On July 8, Banyan announced it had raised $4.3 million in private-placement funding to support the second phase of its exploration program.)

For now, though, the focus is on Phase One, which was enough of a challenge to get off the ground. Christie was in constant communication with employees, contractors, the community of Mayo and the Na-cho Nyäk Dun First Nation, sharing concerns and, later, the company’s plans as government health policies evolved. When it was determined it was safe to go ahead with a summer drill program, Banyan was then tasked with ensuring the logistics planning met public health office standards. Christie searched far and wide to stock up on hand sanitizer and cleaning supplies. She also managed to have fuel delivered to site by a Mayo company without any people having to come into physical contact with each other. “All the extra logistics, there’s just more to think about,” Christie says.

Banyan Gold has been busy this spring for other reasons, too. The company recently released an initial inferred resource estimate of more than 900,000 ounces for Aurex-McQuesten, the culmination of two years of field work. “It was good fortune that when COVID hit, our main activity was putting together that resource, which is a very office-based activity,” Christie says.

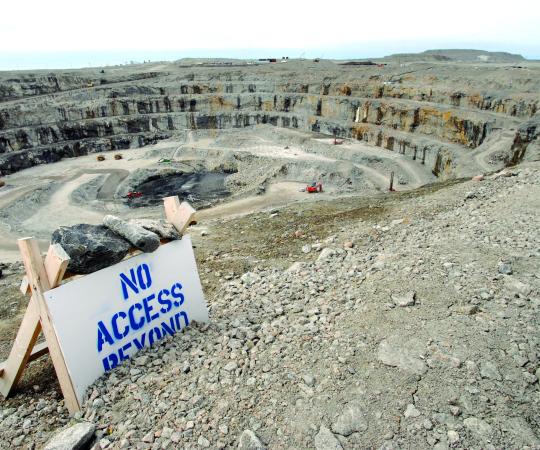

That inward turn has been playing out at other exploration firms, especially those with projects where access is impossible, limited or unclear. Among them is Auryn Resources, which is exploring for gold at its massive 2,700-square kilometre Committee Bay project east of Naujaat in Nunavut’s Kivalliq region. When COVID hit in mid-March, “our share price went down considerably with everyone else’s and the ability to raise capital was extremely limited initially,” says Ivan Bebek, the company’s executive chairman. Although gold prices soon began to surge, the window to work in the Arctic is short, particularly without the luxuries of road access. “It takes some time, in terms of staging and planning to arrange personnel as well as fuel,” Bebek says. On top of that, Auryn Resources carefully weighed the serious health risks associated with working in Nunavut and possibly bringing the first COVID cases into the Kivalliq region and the territory.

Ultimately, the company decided to cancel its 2020 drill program at Committee Bay, and instead focus field work on its properties in Peru and British Columbia to generate news. But Auryn isn’t sitting idle with Committee Bay—it is using this time to drill down on its troves of data, gathered over the last four summers at a cost of $60 million, to come back and drill more prospective targets next year.

The work is generating positive results, Bebek says, noting early tests indicate the company may have been drilling at the lower grade ends of some structures and not the folds that may contain higher grades. Armed with this information, Bebek expects 2021 to be a big year at Committee Bay. “Instead of going up to drill 5,000 metres this year, maybe we can drill 15,000 or 20,000 metres next year,” he says.

The basis for Bebek's confident outlook is the strong price of gold, which he predicts will only continue to rise as governments and central banks respond to the economic fallout from the COVID-19 crisis. For years, Auryn used $US1,300 per ounce as threshold gold price to establish the economic viability of Committee Bay. “That threshold has recently been blown out of the water with current metal prices being over US$1700 [per ounce] gold,” he says.

Bebek says the gold fever may have only just begun, wondering aloud whether prices could soon eclipse US$2,000 per ounce if governments continue to print money and investors turn to gold as a hedge against inflation and weakening currencies. “We anticipate over the next couple of years there will be an extremely robust gold price, which is the best complement you could look for when you go looking for a giant in the Arctic—not only for the value of what you find, but for the ability to finance and perform for your investors.”

While the strong gold price has been a blessing to gold miners—including the Yukon’s placer miners, who are also reaping the benefits of low fuel prices—junior miners looking for other commodities are feeling the pinch.

The timing of the COVID-19 crash in March couldn’t have been worse for North Arrow Minerals (although CEO Ken Armstrong provides “the massive caveat” that a global pandemic is never good). The effects on junior miners would have been different had the pandemic arrived in late fall, when programs would have ended before freeze-up. “You would have had a bit more runway to try to figure out how it’s all progressing and how things can work.”

Work on North Arrow’s Lac De Gras joint venture project with Dominion Diamond Corp.—a 40 per cent partner in the Diavik mine and majority owner of Ekati—was already under way in March but had to stop when the pandemic hit. “[Dominion] went on care and maintenance at Ekati, first of all, and that’s when the exploration program shut down,” Armstrong says. North Arrow also had to cancel work at its Naujaat project, just nine kilometres north of the Nunavut community it’s named for. “Physically, we couldn’t go to Naujaat to do work on the project this summer—or certainly in the shorter term—just with the travel restrictions [in Nunavut] and trying to figure out how exploration can happen,” Armstrong says. “That’s just the reality, and it’s appropriate. It’s really important that the virus does not enter these vulnerable communities.”

Instead, North Arrow worked on a deal with EHR Resources, based out of Australia, to partner on the Naujaat project. With the added time to plan, North Arrow also decided to move fuel and supplies to the project site by sealift this summer for work in 2021, reducing the cost of flying those goods in and, hopefully, allowing them to do more work next year.

Those savings will be welcome. The diamond industry has been struggling at all levels since 2019 due to weak prices resulting from oversupply in both rough and polished markets. The pandemic has only made it worse. Lockdown orders and travel restrictions slowed the supply chain to a fraction of its normal activity as international rough sales centres and polishing factories shuttered operations, and jewellery retailers closed their doors. But Armstrong says while he’s interested to see what prices different diamond categories will fetch when the markets open back up, he’s focused on the future. With an anticipated supply crunch due to the scheduled closure of some large diamond mines, Armstrong’s job is to tell that story to investors to best position North Arrow to capitalize when the market interest swings back to diamonds.

Bulk metals explorers are doing the same thing. “The price of base metals has been taking a hit because of COVID and the lack of demand for the raw materials, so that doesn’t help the base metal guys so much,” says Scott Casselman, head of mineral services for the Yukon Geological Survey. Iron ore, copper and lead-zinc do well when economies are booming and the demand grows for materials to manufacture cars and build houses, roads and bridges. Anyone involved in mining will tell you that the markets are cyclical. Junior explorers must accept the reality that their commodities are out of favour one day, but they still need to take the long view, considering their projects won’t become mines for years or even decades—if ever.

And while a great deal of the speculative investment money might be going to the health industry right now—financing anything from potential vaccine breakthroughs to PPE companies—Gold Terra’s David Suda, who comes from an investment banking background, says he thinks Canadian investors will be ready to strike when attention shifts back to the resource sector. “Where we have an edge in Canada—and certainly in our public equity capital markets—that this has been a resource-based economy for a long time… When commodity prices have a run up, Canadian investors like to flock to what they know.”

Those investors, Suda continues, are happy in the resource sector because they are conversant in the space. “They don’t have to learn what a Phase 3 trial is for some drug. They don’t have to become familiar with whatever finite math is required to figure out the probability of an outcome of a trial,” he says. “Canadian investors love to talk about what they know best—and that’s resources.”

Hitting Pause?

Who’s drilling, who’s waiting and who’s staying at the office this exploration season?

NUNAVUT

Sabina Gold and Silver Corp.

Sabina demobilized its Back River gold exploration in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region in March as COVID-19 lockdowns and travel bans came into effect. In late May, the company announced plans to resume drilling this summer, with COVID-19 safety protocols developed in consultation with territorial, Inuit and community governments.

De Beers Canada

De Beers suspended field work at its Chidliak program this year due to COVID-19 restrictions. Desktop work is continuing involving energy, transportation and remote technology. In May, De Beers hired Arctic UAV to retrieve data from weather and wildlife monitoring equipment at the site.

North Arrow Minerals Inc.

North Arrow cancelled exploration plans this year at its signature Naujaat dia-mond project, known for its unique orange diamonds, due to travel restrictions in Nunavut. It expects to ship fuel and supplies to the Kivalliq region site this summer as a cost-saving measure for future exploration. North Arrow’s joint venture with Dominion Diamond Mines ULC near the Ekati mine was also shelved in March due to coronavirus precautions.

Auyrn Resources Inc.

Auryn Resources cancelled the 2020 drill program at its Committee Bay gold project in the Kivalliq region, west of Naujaat. The company is using the time instead to focus on desk work, specifically a detailed analysis of data gathered over the past four years of exploration.

NORTHWEST TERRiTORIES

Mountain Province Diamonds Inc.

In June, Mountain Province issued a statement confirming that winter exploration programs were cut short in April at both its Kennady Lake project and at the Gahcho Kué mine, in which it is a 49 per cent partner. (De Beers Canada owns 51 per cent of the project.) The company also said it would scale back its summer program and focus on fish connectivity and hydrology work at Kennady. Meantime, it continues with historic data analysis. Exploration activity is expected to resume later this year.

Nighthawk Gold Corp.

Nighthawk Gold suspended exploration at its Indin Lake camp—home to the past-producing Colomac gold mine—in late March. In June, it announced the resumption of exploration, with drilling expected to begin in the first half of July to complete a previously announced 25,000-metre drill program.

Osisko Metals Inc.

Osisko Metals announced in April that it had concluded its winter exploration program at the past-producing Pine Point lead-zinc mine near Hay River due to spring breakup and compliance with public health guidelines. It also said the project would go on care and maintenance due to travel restrictions in the NWT. In June, the company released a positive preliminary economic assessment for the project.

Gold Terra

On July 21, Gold Terra announced that it will proceed with a fully funded 10,000-metre drill program on its Yellowknife City Gold project. The work will focus on high-grade targets in two zones of the project property.

YUKON

Strategic Minerals Ltd.

Strategic Minerals announced in June that it will conduct a summer exploration program on its Mount Hinton gold and silver project in the Keno Hill Mining District. The program includes trenching and road construction, followed by an estimated 7,000 metres of drilling.

Klondike Gold Corp.

Klondike announced in late June that it had begun a summer exploration pro-gram at its 586-square-kilometre Klondike District Property. The first phase of the program will include nine holes at the project’s Lone Star zone, followed by further drilling on the Stander Zone.

Western Copper and Gold Corp.

Western Copper and Gold announced details for a summer drilling program at its gold-copper project on June 4. The pro-gram consists of 43 holes on three zones on its property in southwest Yukon. The company said it expects to complete drilling by the end of the third quarter.

Fireweed Zinc Ltd.

Work at Fireweed’s Macmillan Pass zinc project near the Yukon border with the NWT will continue this summer, according to a mid-June press release from the company. The goal of the program is to conserve cash within the company while developing high-potential drilling targets beyond known large deposits.

BMC Minerals Ltd.

BMC announced in early June that it had started work on an access road to its copper-lead-zinc-silver-gold project in south central Yukon, relying exclusively on community-based contractors to avoid risks associated with COVID-19. All other exploration plans are under review, pending developments in the Yukon’s travel and border policy.

Nickel Creek Platinum

In late May, Nickel Creek announced plans to conduct drilling and geo-physics on its Nickel Shäw platinum project in southwest Yukon this August, pending the successful of conclusion of a financing agreement.