From the tufts of hair left behind after a good back scratch, scientists can determine which—and how many—grizzly bears have visited precise locations in the barrenlands of the Northwest Territories. The bears even get cute names like ‘male 2012-470,’ who just so happens to be an intrepid traveller that covered a straight-line distance of more than 70 kilometres in a week, within the 16,000-square-kilometre area being studied. (And he likely travelled many more kilometres than that, since bears rarely lumber along as the crow flies.)

Two Northern diamond mines, Ekati and Diavik, initiated the Joint Grizzly Bear DNA Project in 2012, in response to concerns that the impacts of mining on grizzlies couldn’t be measured without a baseline understanding of the population. Field studies were completed again in 2013 and then 2017. Here’s what happened.

What they did:

The study area surrounding the Ekati and Diavik mine sites was divided into 113 cells, each one containing tripods wrapped in barbed wire placed in high-traffic areas like eskers and good fishing or foraging spots. These placements were informed by elders and land users from

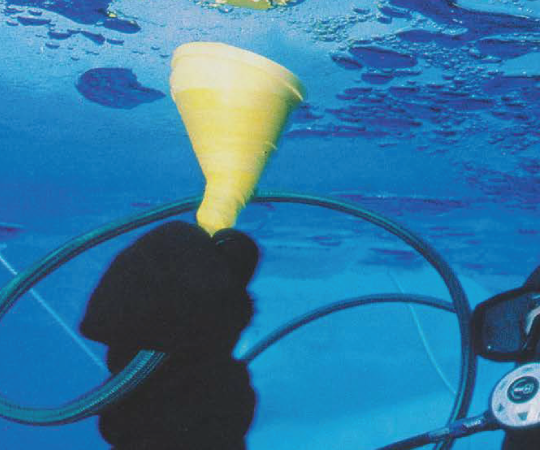

Kugluktuk, Nunavut and the Lutsel K’e Dene and North Slave Metis Alliance. The tripods and the ground beneath them were covered in bait—blood, fish oil, beaver castor, bergamot oil, among others things—to encourage bears to rub up against the tripod and squeeze in between its legs, shedding clumps of hair along the way.

The tufts were collected, packed away and labelled by mine environmental technicians and more bait was poured on at the sites. “There were a few situations where a large grizzly popped over a nearby hill right as we cracked open a bait bottle,” says Sean Sinclair, environment superintendent with Diavik Diamond Mine.

It didn't help that staff were sometimes covered in blood. “It was not uncommon for the putrid blood bottles to, as cracked open, ‘erupt’ on staff because they were under pressure from the heat and decay.” Still, the helicopter was always close by for a quick retreat. (Sites were between 10 and 15 kilometres apart, and they’d check 10 to 15 of them a day.)

DNA was extracted from the hair samples in a lab in Nelson, B.C., to identify the individual grizzlies.

What that showed them:

During the 2012 season, 116 grizzly bears were identified: 43 male and 73 female. In 2013, 136 grizzlies were identified: 60 male and 76 female. (All but 39 of the 2013 bears were documented in the 2012 study.)

Still, some bears weren’t captured because certain hair samples didn’t meet the strict criteria required for the study. And cameras set up at the tripods showed that occasionally bears approached but didn’t rub up against the tripods. They moved on without leaving a trace—or hair—behind.

What they learned:

The baseline study suggested a higher density of grizzlies in the area than was previously thought. When compared to estimates from the 1990s, the population appeared to be stable and possibly growing.

Though the report from the 2017 study isn’t yet finalized, Sinclair (unofficially) says it appears the grizzly bear population in the central barrenlands is stable.

And he’s also learned to practice extreme caution when opening bottles of bear bait.