In a climate where there’s snow on the ground five to seven months of the year, getting around often means using a snowmachine. How else would you get out to that sweet, off-the-map ice fishing hole?

Designed for a white wintery wonderland, snowmachines have traditionally been anything but green. The Sierra Club reports the vehicles consume 188.5 million gallons of gasoline a year in the United States alone. Common two-stroke (sometimes called a two-smoker) models have an especially high carbon footprint—a 2000 study from the University of Vermont reported that a two-stroke snowmachine “burns as many hydrocarbons and nitrous oxides as 1,000 cars.” Although many newer snowmachines use cleaner-burning, four-cylinder engines, you’re still producing carbon emissions every time you go for a rip in the powder.

Aeronautical engineer Stefan Weissenberg wants to fix this problem with a Yukon- grown solution—retrofitting gas-powered sleds to run on locally-produced hydrogen.

Originally from Australia, Weissenberg studied at the University of Sydney before coming to British Columbia, where he worked as part of a team building ultra-rugged, long-distance drones for search and rescue operations. Although the project fell through, it did give him an idea.

“I was researching hydrogen for a long time in the drone business,” he says. “And the idea came to sort of bring that to the Yukon and to the North.”

Still in the prototype stage, Weissenburg (who divides his time between Destruction Bay and Whitehorse) is using a ’90s-era Yamaha VK540, one of those dirty two-smokers, as a test model. If it works, the idea could change the way we move in the North. And it’s not only Weissenberg who thinks so. In April, the engineer’s pitch won the Yukon Innovation Prize, earning him $10,000 to put towards the project.

Provided there are no major setbacks—and no further workspace restrictions due to COVID-19— Weissenberg expects to have a working prototype ready by mid-October, or “whenever the snow falls.”

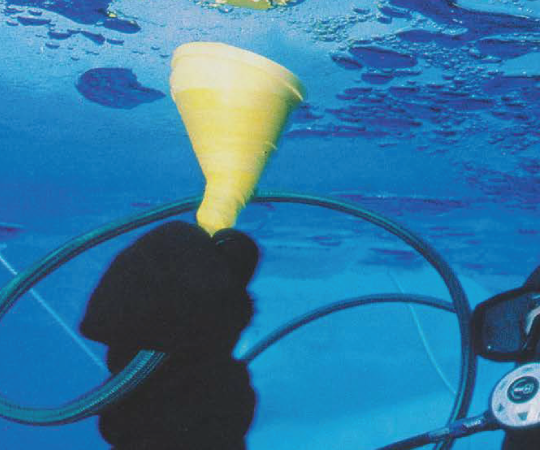

To retrofit the sled, Weissenburg gutted the gas-powered components—engine, fuel and oil tank, drive shaft and transmission—leaving just the chassis and drivetrain (essentially the bones and nerves of the machine) and installed an electric motor, powered by a hydrogen fuel cell. The only part of the whole sled that will need oil is the chain, and the only byproduct of running it will be water and heat.

The hydrogen used to power the sled is three-times as efficient as gasoline, Weissenburg claims, and the two-kilogram fuel cell will give it a range of 300 to 400 kilometres—similar, although maybe a bit less, to what some snowmachines get from a tank of gas. The biggest issue, though, is that around 95 per cent of hydrogen available on the commercial market is produced through high-emissions processes, such

as fracking. What’s the point of making a clean machine that runs on dirty fuel?

Instead, Weissenburg plans to produce hydrogen by splitting water. Using equipment from an American manufacturer, he estimates he could produce two litres of hydrogen a day—enough for one snowmachine battery charge. His hope is that he can get remote Yukon communities— especially First Nation communities—to buy into the idea. That way, they could not only produce their own hydrogen fuel for their snowmachines, but hook the power generators up to the electric grid as well.

And that water and heat this new snowmachine would produce? Weissenburg has a plan for that, too.

“I’m actually working on a system to make coffee for you while you drive your snowmobile,” he says. “You can actually drink the exhaust.”