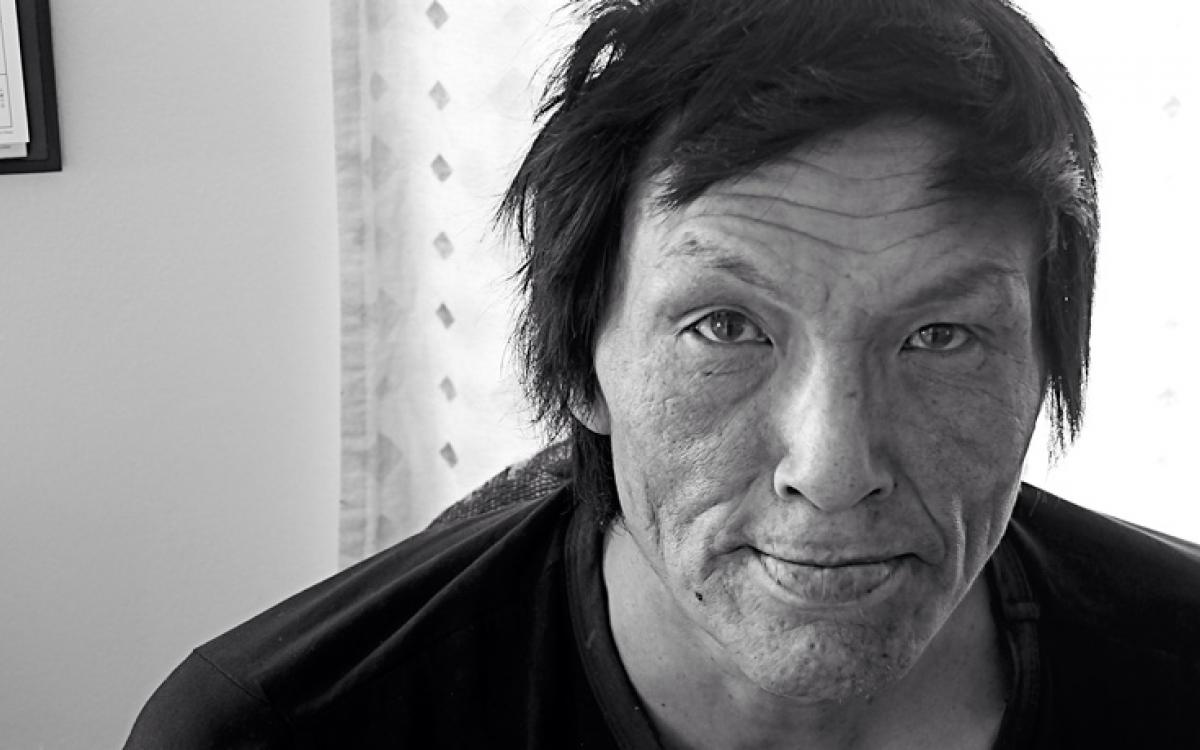

Henry Nakoolak decided to become a carver, he says, when he realized he wouldn’t finish high school. He looks off wistfully, never fully appearing to be totally present in our conversation. He’s more concerned with the carving he has in his hands, finished and ready to sell. He just happened by our door and I had been meaning to chat with him. I offer him coffee or tea; he declines both but finally accepts my offer of a Pepsi.

Henry’s career officially began in 1988 when he sold his first piece to the Co-op for six dollars. He had been fiddling around with various pieces of antler and not taking carving too seriously, but after that first sale, he really started getting into it. “Back then [six dollars] felt like a whole lot,” he says, adding that he knows that the Co-ops sometimes turns around and “triple the price.”

I ask if he had any carvers in his family. He simply shakes his head no, but then recalls with much enthusiasm that his mother used to carve miniatures out of walrus teeth. Henry would sit and watch her delicately bring tiny seals, geese, bears and other arctic animals to life. He ponders that for a brief moment—maybe this was what led him down the dusty road of a carver—then shrugs it off with a wide grin.

He was essentially homeless and living in a shack. He had to borrow power to carve and nearly froze on a number of nights when his Coleman stove ran out of propane.

Many people in town remember Emily, Henry’s mother. She was mute but communicated with sign language. She was known around town as “Uqajuituq” or “Doesn’t Speak.” (Henry’s only sister, Bobbie, is understandably sensitive about the nickname. She doesn’t want her mother remembered that way, especially since she expressed herself very well with her hands. She did speak, Bobbie insists. Just not with her mouth.)

So where does he get his inspiration? “Just my own imagination, just from my own head that’s all,” he says. But when I mention Kenojuak Ashevak, renowned Cape Dorset printmaker, his face lights up. He tells me he once visited the Jesse Oonark Studio in Baker Lake, Nunavut, and bought Kenojuak’s famous Enchanted Owl print on the spot. “Some pictures are alive you know,” he says.

Even at the age of 50, nearly 30 years into his career and countless sales of his art later, he faced one of the toughest years of his life last winter. He was essentially homeless and living in a shack. He had to borrow power to carve and nearly froze on a number of nights when his Coleman stove ran out of propane. He and Anita, his common-law partner, shivered together in their winter parkas and a few blankets trying their best just to make it through to the next day. During the day, Anita would busy herself with sewing projects to sell around town. After nine long months, the couple was finally able to move into a house.

But the livelihood has taken its toll on Henry. His back hurts when he takes deep breaths, without a doubt due to all the dust he’s inhaled over the years. Even though he knows he should wear a mask, most of the time he doesn’t. It’s a matter of priority and cash flow.

Carving a life from stone and bone isn’t easy even for an acclaimed artist like Henry. If you google his name you will see several images of his pieces pop up on various Inuit Art sites ranging in price from $500 to $1500. Door to door, he might get around $60. But sometimes he’s hungry. Sometimes he just wants to buy a pack of smokes.

After a little while I can see Henry is getting restless. It’s been a hard year after all, and he’s got a carving to sell. I thank him for his time and wish him luck. He might head over to the Co-op he says, and with a simple nod goodbye our conversation comes to an end.

An Arctic carver is always on the move in one way or another; if it’s not selling, it’s carving or harvesting soapstone, limestone, antler, beluga vertebrae, walrus jaw, caribou shoulder bones. Whatever he can get his hands on, if he can get his hands on it, he can turn it into something someone’s going to want, and that’s what keep him going.