In the early stages of planning the Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) in Cambridge Bay, engineers selected their preferred construction site and were set to start building when local elders advised them to look for a better location. The planners didn’t know their chosen site was once a waterway the American military had filled in during construction of the DEW Line. Ground instability at the original site could have delayed the project and derailed its budget. Engineers moved the site to another spot recommended by elders.

From early construction through to research conducted on site, local residents and history have shaped the future of the $250 million state-of-the-art facility overseen by Polar Knowledge Canada. The copper-clad and circular building is inspired by the copper Inuit of the Kitikmeot region. EVOQ, the architectural firm that helped design the building, incorporated "the Inuit planning principle of free, open, interconnected spaces [so that] the circular shaped qalgiq (traditional communal igloo) used inside and outside, takes on both a physical and symbolic presence.”

The official opening of CHARS has been postponed several times, but researchers have been working out of the building in recent years during the final phases of construction. The station is expected to become fully operational this summer when work is completed on the main laboratory.

The community-first approach is integral to the CHARS mission. Research programming at CHARS is supposed to be different than other large research-focused institutions. The work will be less theoretical and more practical than research produced at universities, says Polar Knowledge Canada president and CEO David Scott. The needs and concerns of Northerners will influence research.

“It’s important for us that whatever new knowledge we create goes somewhere to do something useful so it can solve practical problems for the people in the North and across Canada,” says Scott. “Say it’s becoming unsafe to travel on snowmachines in certain parts of where we used to travel safely. The ice is less stable. We need to know more about it. You can do a theoretical study of ice or you say, let’s use some traditional knowledge to learn about it and we can take our devices and take some measurements and come up with a risk map for travel routes to minimize the risks.”

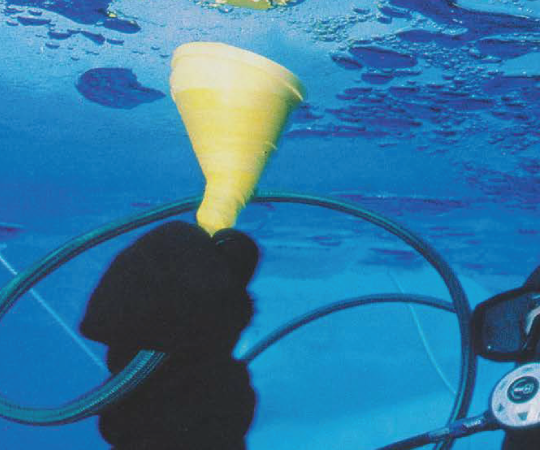

The fanfare around CHARS has generated expectations for meaningful scientific discovery and community engagement. The campus is outfitted to do both. The field and maintenance building houses all sorts of equipment, from snowmachines and ATVs, sonar and sophisticated cameras—there’s even a metal and carpentry shop to fabricate parts on site. The campus also includes dorms, offices, public meeting space, a broadcast studio, and a variety of labs, including the necropsy lab, complete with a lift and operating table large enough to dissect a narwhal.

“Across the entire world, there’s nothing like this in terms of the sophistication of the labs and the design. It’s outstanding,” says CHARS chief scientist Martin Raillard.

The hope is that the unique research capabilities on offer will keep the place busy year-round. Last summer, CHARS recorded about 2,220 research days based on a couple of hundred individual visiting researchers from nine different countries. To date, the greatest international interest in CHARS comes from South Korea, which is complementing its work in the polar south with an increased presence in the North. The polar regions affect global weather patterns so even mid-latitude countries—home to a majority of the world’s population—have an interest in understanding polar phenomenon. “The world is paying attention,” says Scott. “Polar science is a global game. It’s not just the Arctic states. It’s European countries, China, Korea, Japan.”

Originally announced in 2007 by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, CHARS was heralded by the government of the day as an integral piece of Canada’s renewed interest in Arctic development. At a 2012 funding announcement event in Cambridge Bay, Harper said CHARS will “enhance Canada’s visible presence in the Arctic. In this way, science and sovereignty are entwined.” For Arctic researchers and other observers, the investment in polar science was long overdue (the annual operating and programming budget is about $26.5 million).

“Our Arctic is still relatively poorly understood compared to other Arctic countries. We have a quarter of the Arctic in Canada but we don’t have a quarter of the capacity to study that big chunk of the planet,” says Scott. Establishing CHARS will improve Canada’s research capabilities, and it might also help the country’s geopolitical wrangling with other Arctic nations.

“Let’s bring in our international colleagues, bring the additional expertise from beyond Canada to study things that matter to Canada. When you do that, internationals folks recognize our national laws—the permitting requirements, for example—that’s an expression of Canadian sovereignty. That’s not why we do it, but the way we do it contributes to Canada’s expression of sovereignty in the Arctic.”

While the Conservative government set out to establish CHARS as a science hub with a special focus on technology, infrastructure and economic and resource development, the Liberal government changed its mandate to focus more on the environment, making climate change and renewable energy a priority. One project is testing out a composting toilet that doesn’t use water.

“Iqaluit is really concerned about the long-term viability of its water supply,” says Scott. “Are there ways to reduce existing water use to take pressure off the existing supply? There are technologies that function in the south, but do they work in an Arctic environment?”˚

Other projects include gathering data for baseline monitoring of flora and fauna; vegetation mapping of Victoria Island (which will inform wildlife protection and project development on the island, such as where, or if, mines and roads should be built); investigating how climate change is affecting infrastructure; and energy capture technology. Polar Knowledge Canada just finished a round of community consultations that sought direction from residents for what research to conduct. Initial results suggest health and wellbeing will be added to the CHARS mission as well.

A major initiative is establishing the first complete DNA reference library for the Arctic. Researchers are collecting samples of everything that grows or moves to compile an inventory that will eventually include tens of thousands of DNA entries sequenced in CHARS labs. The database will help with everything from food security to wildlife management, says Raillard.

“If it’s alive, we get a sample. We can then do something called DNA barcoding. If a hunter comes in with a dead caribou, we can do an analysis and determine what kind of bacteria or fungus or parasites are in this caribou. Maybe we find an unusually high count of parasites and it looks like lungworm disease is breaking out. Then we can take preventative measures to take care of that.”

Cambridge Bay businesses are eager to see the benefits from the year-round presence of visiting researchers. Infrastructure funding followed CHARS into town, helping to pay for an airport expansion and a new water treatment system. Polar Knowledge Canada is intent on partnering with schools to establish the next generation of researchers. CHARS is capable of broadcasting live events—from lectures to lab dissections—to schools and college campuses. Future plans include science camps. There are also requirements for hiring Inuit and local workers. To date, about 33 per cent of CHARS employees are Inuit.

Raillard, who lives with his wife in Cambridge Bay, says working in the community means being a part of the community. “We believe in living in the North if you do research in the North. Locals have so much knowledge. Many times they can tell us what research is needed and how to go about doing it. That’s what is unique about Polar. We do research for the North, in the North, and with the North.”

The community knows the right questions to help develop research projects, and often know where, when, and how to find the answers, says Raillard. “It’s not enough just to add traditional knowledge. The research is done together. And when you have the data done, you work together to interpret it. At every stage, you work shoulder to shoulder. That’s not just making a better research project, it’s also a respectful way of doing research. It’s reconciliation in action.”

Raillard recalls a recent project at Elu Inlet where researchers working out of CHARS were in the field gathering samples of lemmings and voles to study diseases in small animals. The group worked all day to set up traps with peanut butter only to return the next day to find them empty. Over morning coffee, an experienced hunter from Cambridge Bay heard about their problem and suggested a specific location where deep snow drifts develop in the winter and attract the small mammals, says Raillard. The group returned to the field and set up traps at the suggested site. “Within half an hour, they caught 20.”