In a Northern community, you can always tell when a shipment is about to arrive, or has already missed its arrival date. Grocery store shelves go bare and prices climb. When a cruise ship carrying 1,500 passengers was closing in on Ulukhaktok, NWT the barge bringing equipment and supplies—including port-o-potties—to the town was delayed. The absence of these items was, to say the least, conspicuous.

But there is cargo far more precious than port-o-potties on these ships. Both the governments of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories are tasked with ensuring fuel reaches every community to provide power and heat. Millions of litres of petroleum products are shipped into remote, roadless communities each year. In the North, marine transportation is an essential service. So when a major player in the Western Arctic, the Northern Transportation Company Ltd. (NTCL) was going under, the GNWT swept in to keep the company’s ships afloat, and keep them in the North. But why couldn’t a seemingly necessary service keep itself going?

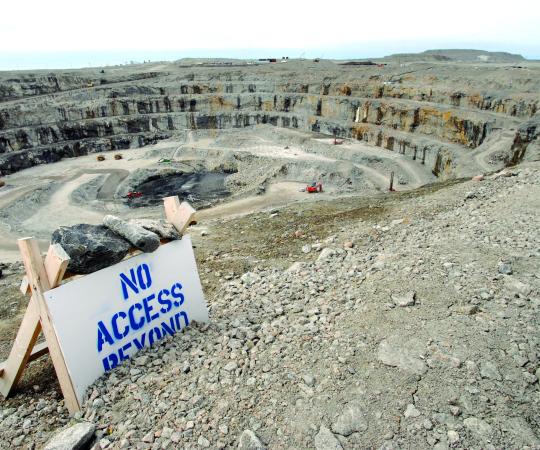

Across the North’s coastal communities and resource development sites, barging companies have long been the main supplier of bulk goods, as long as the waterways are open. But few were surprised when NTCL filed for creditor protection in April 2016. The Hay River-based company’s financial woes were long rumoured—rising fuel prices and a costly employee pension plan saw it spend more than it was taking in. Despite its stockpile of barges, equipment and property, the first monitor’s report—released by PricewaterhouseCoopers after NTCL filed for creditor protection—listed just under $50 million in assets against $121 million in debt. Major government contracts were slipping away from the 70-year-old Northern business.

There was a time when NTCL was the only game in town, moving fuel and other goods across the Western and Eastern Arctic. During the 2006-2007 fiscal year, NTCL competed for 27 contracts with the GNWT, winning 21 of them, including contracts to bring fuel and food supplies to communities and government facilities. But in 2015-16, NTCL bid on only two contracts and was awarded just one of them: to lease out eight seacans in Inuvik.

“There was really no change in the relationship between NTCL and the government. NTCL provided a great business for many years,” says John Vandenberg, assistant deputy minister of Public Works and Services for the GNWT. “Why NTCL’s business went down over the last few years, I honestly don’t know.”

On its final sailing season, NTCL had already shortened its route, cutting Gjoa Haven and Taloyoak, Nunavut out in order to “streamline operations.” An end to its dry cargo delivery to Nunavut communities was threatened in 2003 when NTCL lost its contract with the Nunavut Government to deliver fuel to the Kivalliq region. That contract went to Woodward’s Oil Group out of Labrador.

When word of NTCL's troubles manifested into action, the GNWT began making plans to maintain service to its coastal towns. A comptetion was opened for operators to take on the fuel delivery contract, knowing that NTCL was “going the way of the dodo by the end of the year,” says Vandenberg.

“So, we put out a tender, as typically as we’d done in the past, and the tender was to provide fuel supply and transportation,” he says. “We closed this on November 4 [2016] and got one bid.” The bid didn’t meet the requirements, and the contract was not awarded.

Meanwhile, the government learned in December that a rock-bottom bid had come in for NTCL’s assets. The GNWT acted swiftly and offered $7.5 million for the assets, topping the competing bid of $2.2 million by an Alberta company whose interests were not necessarily to keep the vessels on NWT waters. The government’s bid was successful and given the go-ahead by cabinet. The GNWT became the proud new owners of eight tugs, 57 barges and a shipyard in Hay River. These were assets, Public Works and Services Minister Wally Schumann says the government just couldn’t let go. Even if there wasn’t much of a business case to operate them.

Despite its troubles, NTCL operated a fleet that was specially built to navigate the Mackenzie River right into the Arctic Ocean—as well as the facilities and equipment to keep that fleet running. Ten communities rely on these ˚ services to supply petroleum products (four of those through the NWT Power Corporation), all the way up to Sachs Harbour, on the southwest coast of Banks Island in the Beaufort Sea. The tugs are high-horsepower vessels suited for the shallow river and bays, and can operate in saltwater. Most were built in the 1970s, says Vandenberg, but considering they’re only used three months a year and largely in freshwater, they’ve held up quite well. And Transport Canada makes sure of that—every vessel is checked before it hits the water for the season.

Marine transportation isn’t exactly the government’s forte, but with no one to deliver fuel it was left with few options. The one bid the government rejected in November would have charged $5 million more than the operating costs for the previous year. In terms of fuel delivery, that meant about an additional 30-cents-per-litre for customers, says Schumann—a significant jump in communities like Paulatuk where, on average, home heating already costs $11,000 for the year (compared to, say, $700 in Edmonton), according to the National Energy Board.

Right now, Vandenberg and his team are putting together a sailing schedule for the 2017 summer season, and are working with a marine staffing company to put qualified crews on board the vessels.

The long-term plan isn’t necessarily to continue operating the fleet with the government at the helm, but a small staff has been brought on to manage this summer’s operations—several are former employees of NTCL. By next year, it’s possible an operator will be contracted to take over the route, using the government-owned fleet. At this point, Vandenberg says the GNWT is keeping its options open. The priority is ensuring communities receive their fuel supply, but down the road other business opportunities within marine transportation could come along. Additional freight contracts, both public and private, could be added to the route, says Schumann, but the government has to be careful about competing with the other barge operators that run the river. Business is tough enough already.

Roads, on land and on frozen lakes and rivers, have cut deep into the water transportation business. While infrastructure in the North is limited, those few highways have quickly scraped away at the small customer base afforded barging companies.

In the mid-1980s, Cooper Barging’s business took a real hit. Highway 7 was built in 1984, stretching from the Alaska Highway north of Fort Nelson B.C., into the Northwest Territories from Fort Liard to just south of Fort Simpson. Fort Liard now had access to Fort Nelson and other cities beyond: Fort St. John, B.C., Grande Prairie, Alberta, and even further south to Edmonton. “Before that, we used to supply Fort Liard with all their resupply stuff, so it took that away pretty well altogether,” says owner Michael Cooper.

Nunavut’s sealift contractors Nunavut Eastern Arctic Shipping and Nunavut Sealink and Supply Inc. are busy with their routes during the short shipping season, but they aren’t also threatened by competition coming in with newly built roads.

Cooper had a lot of busy years when oil and gas development was still active around Norman Wells and Tulita, and community resupplies kept their three tugs and nine barges moving. “There’s been a lot of years like that actually,” he says. “It’s only in the more recent times there’s not that much. There was a time when there was lots of work from both sectors: public and private.”

Oil and gas development is delayed indefinitely: Arctic drilling now falls under a U.S.-Canada moratorium, and in the Sahtu region, once the NWT’s petroleum hub, the wells are running dry.

Low water levels are another challenge for barge operators—NTCL vessels ran aground in both 2015 and 2016. Cooper says those changes are something you get used to seeing but so far, water levels haven’t kept his company off the

Mackenzie River.

All of these factors were a part of NTCL ownership’s explanation for its collapse. Will the government have an easier go at it? Well, that’s not exactly the point—this wasn’t a business move, it was a stop-gap measure to keep essential services moving. But there could be opportunities to make money down the line. “I think the economy is a little slower right now and I think that’s going to be a challenge going forward, but having said that, I think there’s quite a bit of opportunity for business out there,” says Vandenberg. The government has been approached to move cargo for private companies, and as per NTCL’s service, dry cargo will still be accepted at the port in Hay River for delivery this season. “Simply serving the government, moving petroleum products to those six communities is not going to keep this service alive,” says Vandenberg.

It’s a challenging business, but it’s a lot easier than building a road to Sachs Harbour.

Does the Northwest Passage live up to its hype?

In 2013, Danish ice-class bulk carrier the Nordic Orion saved $200,000 and four days of travel by taking the Northwest Passage rather then the Panama Canal when shipping coal from Vancouver to Finland. Part of those savings were because 25 per cent more coal could be carried through the deeper waters, according to a Globe and Mail article on the voyage. But the trip nearly didn’t happen—because getting insurance for a voyage through this notorious route is far from simple.

More than 20 years ago, there was a lot of talk in the maritime insurance industry about the passage, says Kevan Gielty, president and CEO of marine insurance company Coast Underwriters. Since then, little has changed: there’s still interest, but all of the risks and limitations remain in place.

The most glaring problem is the lack of infrastructure and resources along this route, compared to the much more developed passages such as the Panama or Suez canals. Gielty likens it to driving on a quiet country road versus a well-travelled highway. If nothing goes wrong, it’s a great option—but if your car breaks down with no one nearby to help, you’re in a tough (not to mention expensive) spot.

And the Northwest Passage really is that tough spot. Canada has two icebreakers in the water during the shipping season, compared to Russia’s 40 that navigate its Northern Sea Route. And Russia’s route has already seen its fair share of traffic—with far fewer islands in the way and year-round navigation since 1978, according to a 2009 report on Arctic shipping by the Arctic Council.

The report found that, “with the exception of the Northern Sea Route, the Arctic is perceived as an unknown quantity or a marine frontier. As a result, the provision of insurance for Arctic shipping tends to be on a case-by-case basis and expensive, with seasonal additional premiums. The availability and cost of marine insurance is a major constraint on Arctic marine shipping.”

While other regions expand and develop new routes for shipping—including a canal through Nicaragua—Hugh Stephens, executive fellow with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy says Canada is shying away from becoming a major competitor by neglecting its own route. Multiple ports and more icebreakers on the water would be a start. While natural features—unpredictable ice patterns and shallow depths along southern portions of the route—are beyond human control, Stephens says infrastructure built to negate those challenges could have the pull to urge more compasses northwest.