Rankin Inlet’s annual family fishing derby is usually a bigger deal. But this year the crowd is small and subdued, even though the trout and cod competitions are on the same weekend. There’s good money at stake—the longest of each species wins $5,000, with decreasing amounts for the runners-up—and it’s a brilliantly sunny and surprisingly warm day. But there’s no line-up at the trout-measuring table and while the cod table is busier, there’s not much excitement. People are mostly shaking their heads about the weather.

Last year, spring came early here; this year it’s even earlier. A month ahead of normal, everyone is saying. May’s average high is -2.9 C. But for more than a week, the temperature has climbed above freezing, even hitting double digits. Although organizers moved the trout derby up a weekend, much of the snow is already gone from the tundra, making it tougher for snowmobiles to reach the inland lakes for the best trout fishing. One couple spent 17 hours returning home, a trip that would usually take two or three hours. Many people just fished for cod on Hudson Bay or didn’t bother entering the derby at all.

The weather was yet another reminder, not that anyone here needed one, that climate change is hitting the North sooner and harder than elsewhere. Obviously, the people who live in the Kivalliq region can’t solve this global problem on their own, but they know that being completely dependent on diesel for power and heating is not helping. And they want to do their part by building the proposed 1,200-kilometre Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link, which would bring clean, renewable power—along with fast, reliable internet—from northern Manitoba to Rankin Inlet and four other communities as well as two mines.

The link would cut Nunavut’s carbon emissions by 371,000 tonnes a year, more than enough to allow the entire territory to immediately meet its 2030 target; save money on buying, shipping and subsidizing diesel; and generate an estimated $8 billion in revenue over 50 years. The Inuit-owned link would also dramatically improve life by cutting the cost of housing and improving education, health care and business opportunities.

For the rest of the country, the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link would serve the interests of Indigenous reconciliation; bolster Arctic sovereignty; and, by finally connecting Nunavut to the rest of Canada, be an act of nation building. The challenge, though, is the funding: The link will cost an estimated $3 billion.

Given all it would offer, selling the KHFL seems like it should be an easy job. Anne-Raphaëlle Audouin leads the pitch team as CEO of Nukik Corp., a company created to develop major infrastructure projects in the region. Her credentials are impressive: a law degree, a master’s in resource and environmental management, and several years of experience working in renewable energy. She has the full-throated support of the Kivalliq Inuit Association, which owns 51 per cent of Nukik, and Sakku Investments, which owns the other 49 per cent. And listening to her talk about the merits of the link, it’s easy to get the impression that the KHFL practically sells itself.

Certainly, it’s an ambitious venture: an overhead transmission line capable of delivering 150 megawatts of hydropower and 1,200 gigabytes per second of high-speed broadband internet to serve the Kivalliq region. The proposed route begins in Gillam, Manitoba, heads to Arviat, then up the western shore of Hudson Bay to Whale Cove, Rankin Inlet and Chesterfield Inlet, and from Rankin Inlet to the Meliadine mine and on to Baker Lake, the only inland community in Nunavut, and the Meadowbank mining complex.

But Audouin and her allies are convinced the need for it is obvious. Aside from a negligible amount of solar power, Nunavummiut are completely dependent on diesel for power and heating. The 24-hours-a-day chugging sound from the power plant in Rankin Inlet is audible from blocks away. It’s just one of 25 diesel plants in 25 communities operated by the Qulliq Energy Corp., the territorial utility. None of the plants are on a grid. Many are old and nearing the end of their lives, making them costly and difficult to maintain and at risk of failure. Replacing them will not be cheap.

Sticking with diesel also means more or expanded fuel-tank farms as local populations grow. Standing up on the hill by Rankin Inlet’s tank farm, KIA president and Nukik board member Kono Tattuinee looks out at the still-frozen Hudson Bay and explains that the environmental damage isn’t just from burning fossil fuels. Delivering diesel to Nunavut, during the few months a year ships can get there, has its own consequences, including for the delicate marine ecosystem. The increase in ship traffic has disturbed the sea mammals that Inuit hunt. In addition, there’s always the danger of spills. As Tattuinee says, “You’re playing Russian roulette with your nature.”

And then there’s the cost to consumers. Even with sizable government subsidies, the bill to heat a home can be as much as $1,000 a month. Worse, a diesel heating system can represent as much as 40 per cent of the cost of a new home. That’s a big problem in a territory with a severe housing crisis, one that exacerbates many of Nunavut’s social ills, including mental health issues, alcohol and drug abuse, domestic violence, and a devastating suicide rate.

As for the global problem of climate change, Nunavut has no hope of meeting the 2030 greenhouse gas emission reduction targets Canada has set unless the territory can get off diesel and move to clean energy. Most alternatives are, for now, not feasible. “We’re not going to be able to decarbonize Nunavut fully with the few solar panels on rooftops,” Audouin says.

Even above the tree line, wind is intermittent power and batteries in the Arctic are unproven technology. And while some people tout small modular reactors as the solution, these tiny nuclear plants are still probably two decades away from being a viable option. And putting them in the North would be highly controversial, geo-politically and environmentally. Besides, SMRs might not be any less expensive. That leaves hydro power as the only sensible solution, according to Audouin. “It’s the right thing to do,” she says. “It’s time to do it.”

Driving around town, Tattuinee talks about life in Rankin Inlet. He’s wearing his Toronto Maple Leafs cap. Old enough to remember when Dave Keon and Eddie Shack were the club’s stars, he’s still mourning the team’s ouster from the playoffs a few days earlier. Going by the old arena, he says, “This is Hockeytown. We’re not talking Detroit here. We’re talking Rankin Inlet, Hockeytown.”

Indeed, the hamlet’s welcome sign says, “Home of Jordin Tootoo,” in honour of the former NHLer who grew up in the community; plenty of teenagers go south for high school so they can play at a higher level; and residents regularly fill the new 950-seat arena to cheer on local teams. They also love going out on the land to hunt and fish and spend time at their cabins. The modern and the traditional blend comfortably here.

Just two generations from his grandparent’s nomadic lifestyle, Tattuinee came to Rankin Inlet as a boy in 1971. Back then, the community had a little over 500 residents; today it has 3,000. A lot has changed, including the introduction of most of the modern conveniences southerners take for granted. Unfortunately, dependable internet access is not one of them and that threatens to put Nunavut—already stuck with a massive infrastructure deficit compared to the rest of the country—at risk of falling even further behind.

Including fibre optics in the KHFL to deliver broadband internet may seem like an extravagance, but the capacity is already a standard part of transmission lines for communications between substations, making controlling and monitoring the system possible. Delivering data for internet would require some minor adjustments, such as the installation of repeaters, but the benefits would be massive. It’s not about streaming movies, playing online video games, or other data-hogging pursuits. When the internet goes down, it’s no minor inconvenience. The Northern Store, for example, can’t take credit cards, meaning people can’t buy food unless they have cash. At the airport, staff must write up boarding passes by hand, delaying flights. Businesses of all kinds suffer.

Although internet access is expensive, many people and most companies have accounts with two or three providers because each plan not only offers unreliable service but also comes with a low usage cap. Even when everything is working, going online is usually painfully slow. “It’s still almost dial-up. Remember the good old ’90s?” Tattuinee asks before making a screeching sound. “That’s what it feels like. And so, lives would change. Businesses would flourish.”

That’s especially important in a place where the entrepreneurial spirit is as evident as the remnants of the old Rankin Inlet Mine, which lie beside the Qulliq Energy Corp. power plant. The nickel operation opened in 1957, employing many Inuit, and a town grew up around it. Although it closed down after only five years, it left its mark and Rankin Inlet is now the business hub of the region. But David Kakuktinniq, the president and CEO of Sakku Investments and the president of Nukik, knows bad internet is holding Nunavut businesses back.

He logs into an average of six Microsoft Teams meetings a day. To cope, Sakku has accounts with three internet providers, Qinniq, Northwestel and Starlink. “And if there was a fourth one out there, I’d buy it too. Every one has its attributes, but every one has its failures,” he says sitting in his boardroom and wearing a blazer, not a common workday clothing item here. “So, what would fibre do for us? It would change us 100 per cent.”

A boost to business is the least of it. Health care would also improve. The dodgy internet can make sending and receiving even simple diagnostics troublesome. Medical staff sometimes must resort to sending handwritten notes over fax machines while patients wait in the emergency room. Better internet would also improve telehealth, saving on medical travel, something that costs territorial government more than a $100 million a year. Even residents of a larger community like Rankin Inlet residents must go to Winnipeg or elsewhere in the south for most medical procedures, including births.

Broadband would also transform education. While online learning and internet access enhance schooling in the rest of the country, Nunavut students must contend with frequent outages and buffering videos. “What’s it worth to a child,” Kakuktinniq asks, “to be able to get a proper education?”

Many young people leave the territory for universities in the south. Lots of them don’t return. And the people who do return, or never leave, should have the same advantages as everyone else in the country. Tattuinee, who has six children and 14 grandchildren, says, “I want them to have a better life than I did.”

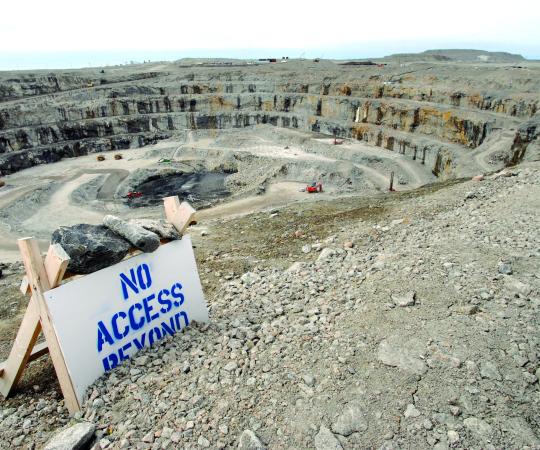

Never having to contend with dismal internet would make life better. So would the job opportunities that hydro would create. A quarter of the KHFL’s load would go to the Qulliq Energy Corp. to serve its residential and business customers. The remaining 75 per cent would be for Agnico Eagle’s mining operations at its Meadowbank Complex, near Baker Lake, and at the Meliadine mine, which is 25 kilometres from Rankin Inlet. Meadowbank now uses about 90-million litres of diesel a year and Meliadine goes through 50 million litres. But the latter mine is undergoing a $400-million expansion that will see its consumption go up 20 per cent. Meliadine’s projected mine life now goes to 2032, but the company has begun the regulatory process to extend that a decade if potential satellite open pits or underground operations prove economic.

Agnico Eagle has made a company-wide commitment to reduce its emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 and to be net carbon zero by 2050. It’s making progress in the rest of the world, but despite determined energy-efficiency efforts, meeting those targets in Nunavut likely won’t be possible without the KHFL. “This would really move the needle much more than anything,” says Martin Plante, the company’s vice-president of Nunavut operations. “It would have a big impact on our current operations, but also for further mineral development in Nunavut. It’s going to allow a sustainable economy to develop.”

The prospect of more mines obviously strengthens the case for the link. The Kivalliq region sits on the Canadian Shield, but exploration of the mineral rich pre-Cambrian rock has been minimal because the lack of infrastructure makes it difficult and often prohibitively expensive. Currently, hopes for critical minerals are high. Canadian North Resources, an exploration and development company, for example, has already identified nickel, copper, cobalt, palladium, and platinum on its Ferguson Lake property and believes there’s potential for lithium. More controversially, the hunt for uranium in the region has begun again.

In addition, hydro lines deliver power in both directions. Certainly, Nunavut has lots of water to harness, as Kakuktinniq is quick to point out. But building hydroelectric sites is expensive, so Audouin thinks wind farms might be a more realistic way for the territory to become an energy exporter. Even though the power is intermittent, Nunavut could sell it back to the grid when there’s a surplus.

But for everyone at Nukik, the link’s importance is not just about the environment, the economy or how it will improve life. The KHFL is for all of Canada. Building the Inuit-owned line would be an act of Indigenous reconciliation. The investment in the North, and the resulting population growth and business activity, would also strengthen Arctic sovereignty. In addition, the Americans are pushing Canada to do more on defence as geopolitics become increasingly fraught. The Department of National Defence already has a presence in Rankin Inlet and the link might make expanding operations in the territory easier.

Nunavut has a tiny population, but geographically, it’s one-fifth of the country. Yet people here don’t feel connected to the rest of Canada. Because they aren’t. They’d like to be, though. Audouin defends the territory like a long-time resident even though she’s originally from France, where she did her undergraduate degree before moving to Canada. She’d never been to Nunavut when she joined Nukik in March of 2022, but now sees the KHFL as an act of nation building.

While there are currently only 11,000 or so residents in the Kivalliq region, the population is sure to grow, especially if the link gets built. Audouin likes to use the analogy of the Canadian Pacific Railway, a massive infrastructure project that connected the southern part of the country from east to west. Canada’s population was a little over four million people when construction began in 1881. “The leaders at the time didn’t build it for four million Canadians. They built it for the future,” Audouin says. “I’m convinced that Nunavut can be an economic engine for Canada. It can be defining how we write the next chapter of our story as a country.”

As it turns out, though, Audouin’s job is not as easy as it seems. A crucial first step to building the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link is securing the financing. So, much of her time is split between government relations and public relations. A registered lobbyist, she’s based in Ottawa but travels a lot to convince stakeholders of the link’s merits and keep them motivated and engaged, while also raising awareness of the project and of Nunavut. Selling the KHFL locally isn’t hard. At community meetings, some residents express concerns about the effect on wildlife—caribou migration, for example—particularly during the construction. But people know they need the link.

Outside the territory, getting support in principle is not a problem, but Audouin knows the objections well: It’s too costly; it’s too remote; it would serve too few people; and it’s never been done before. In fact, though, a similar venture is already well underway in northwestern Ontario. The Wataynikaneyap Transmission Project, an 1,800-kilometre hydro line, expected to be completed in 2024, will take 17 remote Indigenous communities off diesel.

Adam Borowiecki, who was senior manager on Watay, is now Nukik’s director of projects. He expects construction of the KHFL will take four years. The link would include three power lines and one fibre-optic cable running on roughly 4,000 towers, most under 30 metres in height and spaced 350 to 400 metres apart.

During construction, workers will create rough trails to move equipment. Afterwards, they will restore the ground and do any required maintenance with helicopters or snowmobiles and ATVs. The route is largely flat and most of it is above the tree line, reducing the need to cut through forests. On the other hand, workers will have to deal with permafrost as well as limited daylight and harsh weather during the winter. But planning and logistics, especially delivering equipment and materials during the short barging season, will be far more complicated than the construction. Hydro lines have been around for well over a century and although no one has ever built one in Nunavut before, they exist in northern Scandinavia and Russia. “This is a very realistic, sustainable project,” Borowiecki says. “We’re not experimenting with the North.”

So, when people say, “It’s not about the why, it’s about the how”—a sentence Audouin admits she’s sick of hearing—they are talking about how to pay for the link. The revenue estimate of $8 billion is based on anticipated electricity and fibre optic capacity sales given the population growth forecasts in the five Kivalliq communities and the expectation that at least one mine will be in operation over the next 50 years. That outlook has helped Nukik line up $2 billion from the Canada Infrastructure Bank and private equity.

Agnico Eagle chair Sean Boyd has long been an outspoken advocate for government investment in Nunavut infrastructure, including the KHFL, although the company has declined to invest directly in construction of the link. “To us, it’s really a community-led project,” Plante says. “Of course, we see ourselves as a partner for the Kivalliq Inuit Association and Sakku and we want to be a key user of this energy, but we really think that it’s a project that goes far beyond Agnico Eagle.” The more likely scenario is that the company agrees to buy the power it needs and pay an additional tariff. But no agreement is in place yet.

So, Nukik is short $1 billion. One advantage the $1.9-billion Watay transmission line had was financial support from the province of Ontario. While the Government of Nunavut supports the KHFL, it doesn’t have the money to help pay for it. That leaves the feds.

A funding commitment from Ottawa has so far proved elusive. Although the territory has only one seat in Parliament, a project that would reduce carbon emissions, be acts of both reconciliation and nation building, and strengthen Arctic sovereignty sounds like a dream policy for the current government. Except that the Liberals have a well-earned reputation for being much better at talking about doing things than at delivering them.

In March, the federal budget included only encouraging words and promises of a tax credit on equipment, which Kakuktinniq insists is a woefully inadequate way to help pay for the project. Although Nukik issued a press release saying it was pleased the government had once again mentioned the KHFL in a budget, Audouin, Tattuinee and Kakuktinniq now admit to being disappointed and, frankly, surprised. They believed the money was coming.

Now they must wait for the fall economic statement. If it includes the funding, Nukik will be able to start construction by the end of 2026 with the line going into service by the end of 2030. Failure to get funding in the fall endangers the project. “It’s not just you lose one day, it’s one day delay on the schedule. It’s exponential from there on,” Audouin says. “So, we would have to go back to the drawing board and really understand what the impact is. But it would be a significant impact.” For one thing, the estimate of $3 billion in capital costs is in 2022 dollars. The longer the delay in starting, the more that figure will grow, especially in an era of high inflation and supply chain constraints.

The KIA and Sakku created Nukik because they wanted to take ownership of the project and to ensure the link would stay in Inuit hands. “We put our money where our mouth is,” Tattuinee says, adding that it’s now the government’s turn. “They have to put their money where their mouth is. That’s what we’ve been doing. We’ve invested in this. We’re all in.”

The KIA is a political organization, while Sakku is a for-profit business. So perhaps it’s not surprising that Kakuktinniq is more outspoken on the subject. “Reconciliation is something that happens when two sides of the table come together. This is not reconciliation, this is a negotiation,” he says, admitting that he was hurt by the last federal budget. “We’re asking for crumbs again. We’re asking for something that we know we need. But, no, this is Ottawa again telling us what’s good for us and what’s not.”

Despite the frustration, no one at Nukik—Inuktitut for strength or power—is willing to give up. “We are still very optimistic and enthusiastic about developing the Kivalliq Hydro-Fiber Link,” Audouin says. “There’s still that very strong degree of passion and perseverance, and it’s in the DNA of Inuit. They don’t let go. They really persevere as people.”

If that perseverance pays off in funding for the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link, Audouin will have a new job. She’ll be able to stop selling and shift her focus to overseeing the construction of the line. And then she and Nukik can get to work on other projects that will benefit Nunavut.