It was Christmas Day 1893. The expedition ship Fram, frozen tight in the polar pack ice north of Siberia, drifted slowly across the Arctic Ocean. In the ship’s cozy saloon, a small group of Norwegian explorers, thousands of miles from their loved ones, celebrated the day with a sumptuous feast of oxtail soup, fish pudding with potatoes and butter, roast reindeer, French beans, cranberry jam, cloudberries with cream, and marzipan. Coffee, dried fruits, and a selection of cakes followed.

The next day, the ship’s commander Fridtjof Nansen, still stuffed from his five-course meal, confessed to feeling “almost ashamed of the life we lead, with none of those darkly painted sufferings of the long winter night which are indispensable to a properly exciting Arctic expedition.”

Nineteenth-century Arctic exploration tends to conjure up images of poorly attired and famished men needlessly hauling sledges or freezing in melancholy and damp quarters below deck. And in the majority of cases, those associations are apt.

But looking back at the Christmas celebrations of the explorers who over-wintered while seeking a Northwest Passage or the North Pole, we find joyful accounts of banquets, music, games, gift-giving, and camaraderie. Far from being just another day, Christmas was a light in the darkness for officers and crew who were largely confined to their cramped quarters around the ship from November to February. Celebrating the festival was crucial for morale at a time when feelings of depression were threatening.

Sledging, cleaning, cooking, or navigating—the work of an Arctic explorer was laborious and monotonous. Staying warm and active in freezing temperatures demanded lots of calories, but the typical rations of ship’s biscuits, bread, and salted pork were bland and never met the men’s daily requirements.

It’s no surprise Christmas was anticipated by all as a time of plenty, when double rations were issued and officers and crew had access to special food and drink. Robert McClure, commander of HMS Investigator, put it best when he said that sailors have 52 Sundays “one just like another—and only one festival, Christmas, when Jack must have roast beef and plum pudding.”

Christmas Day followed a familiar pattern on the large British naval expeditions of the nineteenth century. Divine service was given in the morning and, as officers and men dined separately, a ritual followed in which the men would invite the officers to inspect their messes below deck. This was an opportunity for the crew to display the decorations, banners, and chandeliers they had made for the festive event.

During Christmas in 1875 on the HMS Alert, frozen into the Lincoln Sea north of Ellesmere Island, the officers were led by a drum and fife band below deck to the tune of “Roast Beef of Old England.” The officers saw the men’s quarters “tastefully decorated with flags, coloured tinsel paper, and artificial flowers.” Some years earlier, Leopold McClintock commended his crew for their tables laid out “like the counters in a confectioner’s shop, with apple and gooseberry tarts, plum and sponge-cakes in pyramids, beside various other unknown puffs, cakes, and loaves of all shapes and sizes.”

The crew on Arctic ships ate around noon and Christmas dinner was usually made up of preserved vegetables, beef that had been kept frozen in the rigging, and local game if any was available. Crews especially coveted desserts and sweetmeats. Plum puddings and mince-pies were essential components of the traditional British Christmas at the time and the inclusion of these foods in the celebrations acted, in the words of McClintock, as “powerful stimulants to memory”—reminders the men were connected through these special foods to their loved ones back home.

Officers usually dined in the gunroom around 3 p.m. Predictably, their fare included wine and was of a superior quality to the crew’s. In 1852, Captain Henry Kellett of HMS Resolute even enjoyed a complete preserved Christmas dinner from the exclusive London department store Fortnum & Mason.

After dinner, attention turned to toasts, music, games, and general merry-making. Just as shipboard newspapers and theatrical productions inspired the creativity of the crew, communal sing-songs helped men to relax and cope with stress on long expeditions. “The poets amongst the men,” noted McClure on HMS Investigator, “composed songs, in which their own hardships were made the subject of many a hearty laugh.” Examples included “An Arctic Christmas Song” and “Song of the Sledge.”

Usually fiddles and Jew’s harps were readily available on ships, but during the festive season sailors would make music from anything. While over-wintering at Fort Conger, one of the northernmost points of present-day Nunavut, American Adolphus Greely remembered how the night watch on Christmas Day was enlivened by a concert from “a well-managed band, in which the tinware of the expedition played an important part.”

Christmas was also a time for the crew to symbolically challenge the authority of the officers on Arctic ships. This was borne out on occasions when they elected Saturnalian fellows like the “Lord of Misrule” and the “Boy Bishop”—traditional Christmas characters who inverted the master-servant relationship.

A diary entry from one of William Edward Parry’s officers notes how Parry was disturbed on Christmas Day by the two boatswain’s mates, with powdered heads and brooms, who requested his pipe or Silver Call and then asked that he “resign his office and take the lowest grade of duty in the ship, that of sweeper. The sweepers in return took upon themselves the duty of the former, the order of things being reversed.”

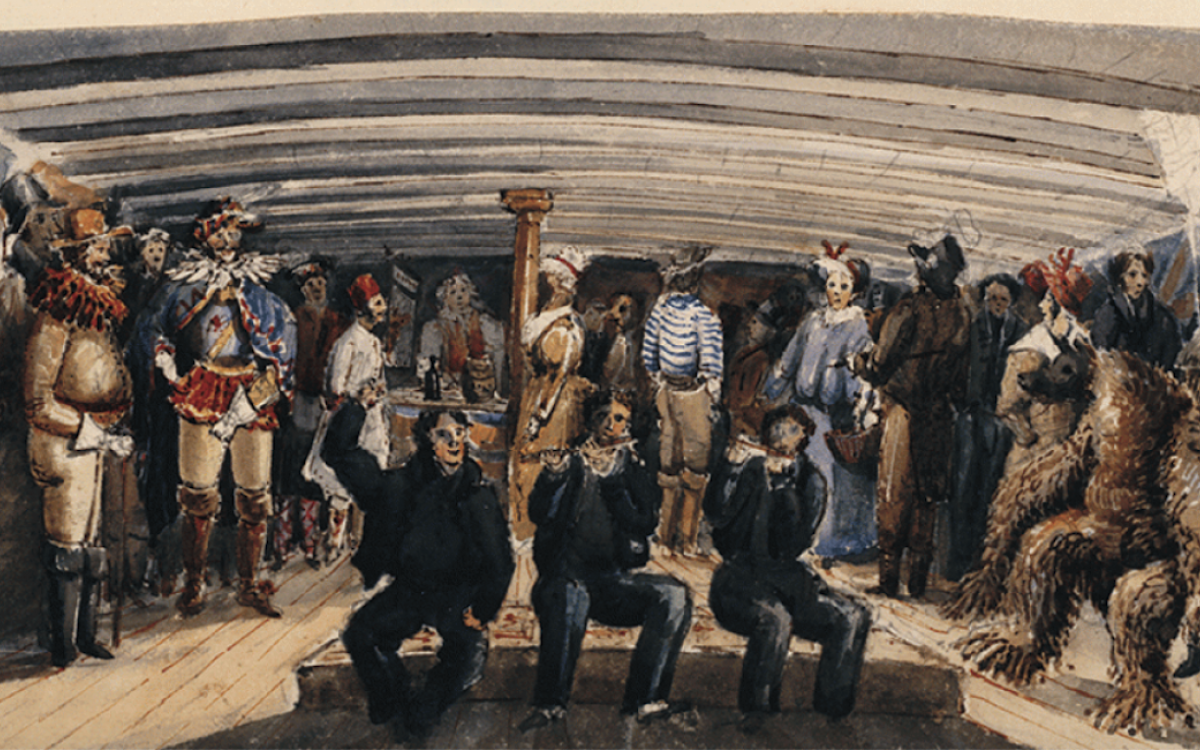

Another symbolic inversion was cross-dressing—a typical practice for explorers during the festive season, when plays and masquerades were performed to keep the men busy and improve morale. However, the extremely cold temperatures on the ice—and even below deck—meant that dressing up as a woman in the Arctic was “no joke in petticoats.”

Nevertheless, by all accounts these seasonal entertainments were great fun. For Christmas 1854, Elisha Kent Kane’s crew performed the The Blue Devils, a comedy featuring a six-foot Irishman playing Annette. Wrote Kane: “I might defy human being to hear her, while balanced on the heel of her boot, exclaim, in rich masculine brogue, ‘Och, feather!’ without roaring.”

On other expeditions, the merriment of the crew did not last past Christmas Day. While trapped in the ice north of Hudson Bay in 1836, Captain George Back was exasperated by his crew’s “perverseness and sluggishness” on Boxing Day. Rather sadistically, he forced the crew and officers to play football on the ice, despite noting their “numbness of limbs, affections of the gums, and other symptoms of scurvy.”

In many cases, that sluggishness can be explained by the indulgence—or over-indulgence—the night before. Polar commanders going all the way back to Jens Munk, who over-wintered at the mouth of the Churchill River in 1619, reported good behaviour among the crew at Christmas despite an increased alcohol allowance. However, alcohol-related indiscipline could be a serious problem on British expeditions in the nineteenth century, especially if crews weren’t permitted to drink. Although Back allowed his men alcohol (beer was considered an anti-scorbutic at the time), tensions between officers and crew quickly arose if the commander insisted on combating scurvy through exercise and abstinence.

This occurred on Christmas Day 1832 when the men of John Ross’s Victory expedition—sponsored by the gin magnate Felix Booth—had to make do with lime juice to drink. Although Ross wrote in his journal that “there was nothing to drink but snow water,” a crewmember later revealed that the ban on alcohol extended “only to the seaman’s berth,” for judging by the smells and sounds emitted from the officer’s berth “a conjecture was formed, that lime juice was not the only beverage, with which the officers regaled themselves.”

Given the men’s taste for grog, shipboard brewing was a constant, if unauthorized, practice and the abnormal intake of alcohol during Christmas could affect the health of the crew. Although Parry’s men were sent on a run and then “danced sober” on Boxing Day in 1821, the following year he noted despairingly that Christmas Day did not pass “without producing… several serious cases of disordered bowels.”

If crews over-imbibed, they were just getting into the Christmas spirit. By the 1840s, the Victorians had invented many of the traditions we associate with Christmas today—feasting, merriment, and quality time with one’s family. It must have been deeply frustrating for Arctic expedition leaders to create this atmosphere given the challenges of exploring in the far North and the enforced social interaction with scores of other men for long periods of time—sometimes years. Commanders tried to encourage camaraderie on board by preparing for the festivities and through the symbolic presence of women and loved ones recognized by toasting, cross-dressing, and the opening of gifts.

Although commanders understood Christmas celebrations were good for the well-being of their men, they may not have realized that feasting on fresh meat, dried fruits, and sweets also gave their crews a significant nutritional boost—albeit temporary. A psychological salve and a physical respite from the dreaded scurvy, Christmas was more than just a meal: it was a festival of light and hope, and a crucial morale-booster for men on perilous expeditions in the Arctic.