I still remember the movie nights at Bathurst Inlet Lodge.

Every so often, Glenn and Trish Warner, the lodge’s owner-operators, would rent a movie projector from the library in Yellowknife and bring in films. But these showings weren’t for the lodge’s guests—they were for the families who lived in the tiny settlement.

As we set up the projector and screen, Robert Akoluk or John Haniliak would climb atop a distinctive dome house they’d helped to build years earlier, draping a blanket over the skylight and hanging blankets over the windows to dim the room. People would throng into the small house, sitting on beds, chairs, boxes, and kids on laps. It would be hot and quiet, as we would wait for the film to start. These were nights everyone in the community looked forward to.

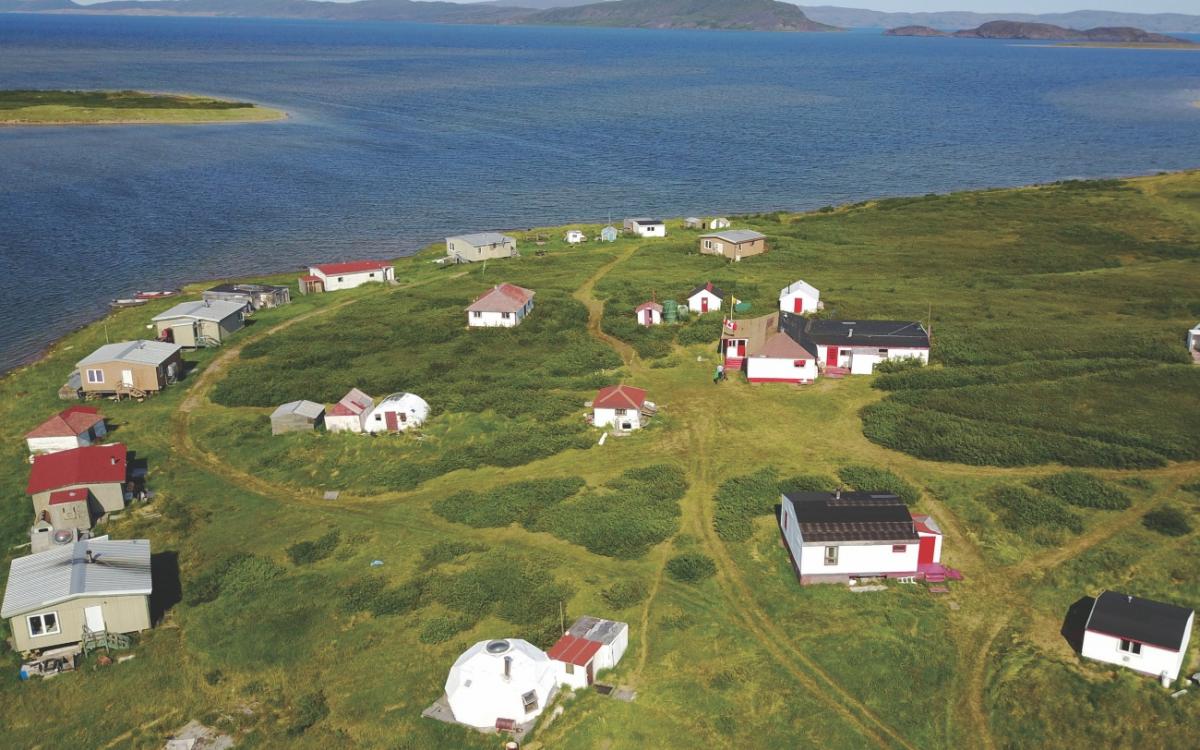

Although no one lives in Bathurst Inlet year-round today, residents return in the summer to run the lodge, enjoying a traditional lifestyle in the beauty of this Arctic oasis. And for a while, those humble dome structures served not only as crowded movie houses, but as permanent residences for a few of the families who called the place home.

Bathurst Inlet (or Kingoak), roughly 200 miles south of Cambridge Bay, is one of Nunavut’s oldest and most isolated communities. From the mid-1930s to 1965, a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post operated there, until a drop in fur prices worldwide made the trading post impractical and it closed. Without people coming to trade, the community’s small Roman Catholic mission church found its relevance waning, so it was deconsecrated and abandoned.

Around this time, Glenn Warner, an RCMP officer stationed in Cambridge Bay, and his wife Trish, purchased the church. The couple, along with some business partners, also bought the HBC post buildings and the land on which they stood. They eventually converted the buildings into the lodge, which opened in 1969 and catered to visitors interested in Arctic wildlife, Inuit culture and natural and Northern history. The Kingaunmiut, local Inuit, bought into the lodge in the 1980s and are now majority shareholders.

Some Inuit families lived around the HBC post during the decades it operated. They worked for the traders as needed, but pretty much lived in the old ways—travelling by dogteam in winter and small freighter canoes in summer. As expert trappers and hunters, they were very capable on the land, but with the closing of the post, they were unable to trade furs or find reliable work. With the opening of the lodge, the Warners reassured the families there would be summer employment, at least.

Back then, the families lived in a combination of canvas tents combined with old packing crates, caribou skin panels and whatever lumber they could salvage from the post. These houses were tiny and used mostly in summer, as snow houses were warmer in winter. The families had no modern stoves, and most cooking was done either on Primus stoves or outside, using small fires fueled by willows.

The Warners felt strongly that if people were going to work at the lodge and live in the tiny outpost camp year-round, they needed better housing. Yet, housing provision was in its infancy, and the government was not well equipped to supply houses in remote camps. Glenn Warner began researching affordable structures that could work in this Arctic locale. Around this time, Buckminster Fuller, the visionary American architect, was experimenting with geodesic dome houses, which looked somewhat like igluit. Bathurst Inlet—called ‘nose mountain’ by Inuit—is a windy place in winter and Warner reasoned domes did well to shed the wind.

Warner found a geodesic dome supplier in Edmonton. With some financial help from NWT Commissioner Stu Hodgson, he purchased the materials and arranged transport for four houses. The dome homes were flown north via Hercules aircraft on the sea ice in 1971 because, in those days, the sealift was not reliable. The materials were accompanied by a skilled southern builder who knew how to assemble them. He worked with locals John Haniliak, Robert Akoluk, John Nanagoak, and Henry Kamoayok to erect the houses. The domes sat on wooden platforms so they did not contact the permafrost, as the heat from the house would thaw the ground, causing the structure to sink and tilt.

At 25-feet wide, the dome houses were put together with pentagonal pieces that comprised of five inches of insulating foam sandwiched between an exterior metal surface and interior composite wood paneling. Two windows in each house allowed cross-ventilation, and a ceiling skylight let in additional light. The houses were heated in the early days by woodstove, but then oil cookstoves or cooking-and-heating hybrids were installed. Kerosene lamps supplied light during the long winters.

At first, these houses were acceptable to the Inuit families, as they did not depart wildly from what they were used to with the iglu. The whole family was housed in one room, with one source of heat and protection from the wind. Usually there was a large bed for all family members, a small table and shelves where food was prepared. There might also be a couple smaller trundle beds for some of the kids. In each house, there was a hanging wooden drying rack for clothing, kamiit (boots) and other equipment.

Each family built onto the dome as needed. In every case a porch was installed. (This is also typical of an iglu.) This sheltered entryway provided additional space to hang outer clothing and to store meat. In some cases, external rooms for honey buckets or other storage rooms were constructed.

Ventilation was always a problem in the domes, especially with many people living inside the house. Condensation formed on the ceiling and dripped constantly. In an iglu, you can simply stick a block of snow on the leak to stop it, but this doesn’t work when the ceiling is out of reach.

The families eventually outgrew the houses and as some of the younger men like Sam and Allen Kapolak and Boyd Warner learned carpentry, they built larger houses based on modifications to tent-frame designs. This meant better insulation in the floors, as well as more floor space. Later, the government supplied modular homes, which are well-maintained and used by the families today. There is no housing association and no complaints to the government to repair houses—everyone looks after their own home.

The dome houses were left mostly unused, while some were claimed for storage. The years took their toll on the structures, but they’re still standing.

As the naturalist for Bathurst Inlet Lodge, I needed a place to live, but I did not want to take up a guest room. I asked if I could stay in the last, livable old dome house and I’m pleased to report I’ve now used it virtually every summer for the past 25 years. To my mind, it’s ideal for me and my dog—albeit, in the summer. The dome house also preserves some of the history of the community, while remaining one of the coolest places in camp. Plus, it doesn’t use up housing space needed by other residents of the community.

Geodesic domes were not uncommon in the past in other Arctic communities, including Cambridge Bay, Pond Inlet, Inuvik, and others. Long-time Nunatsiaq News journalist Jane George has documented some of the dome structures she’s encountered through her extensive travels of Nunavut, on her blog (‘A date with Siku girl’). She notes that domes have hosted an arena in Rankin Inlet, the popular Kamotiq Inn greasy spoon in Iqaluit, and even a church in Baker Lake.

Sadly, most of the domes around the North have been torn down or sit in disrepair. Will they make a comeback? Maybe as greenhouses, or tiny summer homes. But they probably won’t be suitable year-round homes until real investments—in imagination, technology, and cash—are devoted to making them livable throughout the winter.