Mining companies in the North face a specific challenge that has little to do with the science and engineering of discovering and developing deposits. They also need to demonstrate their commitment to ensuring their projects benefit, support—and even celebrate—local communities. Their efforts come in many forms, from complex socio-economic agreements to investments in community infrastructure, scholarships and local sponsorships. Golden Predator Mining Corp., a Vancouver-based precious metal developer working in the Yukon, has come up with an especially creative program to put a face on its commitments. And it starts with a simple question: Where does Yukon gold go once it’s been mined?

For the most part, the answer is “outside the territory,” shipped to other places in Canada and abroad for processing and sale. In the interest of keeping some of that production in the territory, Golden Predator has created the Yukon Mint, a fully-owned subsidiary that produces coins with Yukon materials and imprinted with Yukon art. “It really started as a way to engage the community in the projects that we were running,” says CEO Janet Lee-Sheriff. “The bottom line is we need more wealth staying locally [within the territory] and finding ways to do this is a priority.”

In creating the Yukon Mint, Golden Predator took a page from early Canadian history. Up until the early years of the 20th century, Canada had a similar issue around its gold production; the precious metal was being mined, but there was nowhere to process and mint it. In response, the federal government created the Ottawa Mint, which later became the Royal Canadian Mint. “Ninety per cent of the gold that came out of the [Ottawa] Mint in coin form was from the Klondike Gold Rush,” Lee-Sheriff says. “I looked at it and thought, ‘why don’t we try to do the same thing?’ Instead of sending the gold outside the Yukon as you produce it, why don’t we have a mint ... and keep more wealth in the North?”

The first two batches of coins, produced in 2018 and 2019, were made entirely with gold from bulk testing done at 3 Aces, an exploration project then owned by Golden Predator in southeastern Yukon in the traditonal territory of the Kaska. Both these mint sets were produced as part of a socio-economic relationship with the Kaska, in which the First Nation was given a percentage of the coin sales, in addition to other funds from their socio-economic agreement with Golden Predator. The coins also featured work from Gordon Peter, Dennis Shorty, and Miranda Lane, all artists of Kaska heritage.

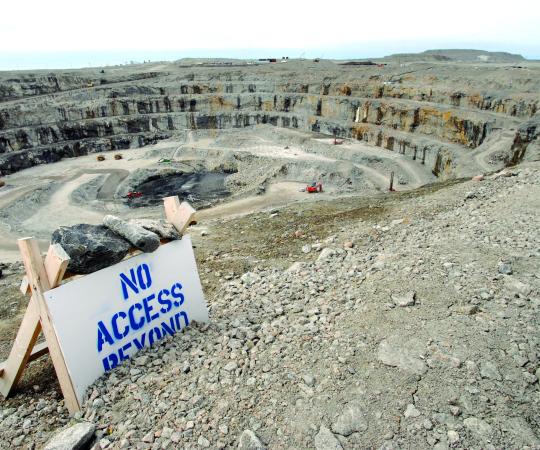

The 2020 batch of coins will be a little different, however, Lee-Sheriff says. Golden Predator sold the 3 Aces site to Seabridge Gold Corp at the end of March to focus on its main project, the Brewery Creek mine. (A past-producing mine near Dawson City, Brewery Creek closed in 2002 following a downturn in gold markets.) The sale means a loss of access to the gold the Yukon Mint was using to make the coins, which had originally come from bulk sampling programs at 3 Aces. Golden Predator has some inventory left, but is looking for another source, hopefully from the Yukon, Lee-Sheriff says.

The 3 Aces sale also means an end to the Yukon Mint’s exclusive relationship with the Kaska First Nation, although the Kaska still have around $300,000 coming to them from the project as part of the community development fund, Lee-Sheriff says. In the future, the share of the coin profits that previously went to the Kaska will go to whichever First Nation the artist featured on the coins belongs to, Lee-Sheriff continues. Golden Predator also hopes to develop a similar working relationship with the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, with whom they have an agreement regarding the Brewery Creek mine, as they had with the Kaska.

For the 2020 coins, Lee-Sheriff, who lived in the Yukon for many years and has been a long-time volunteer and advocate of sports in the territory, decided to support the Arctic Winter Games, following the cancellation of the 2020 AWG due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To honour the Games, Lee-Sheriff reached out to both the AWG council and respected Kwanlin Dun First Nation artist, Brian Walker. Walker, a copper sculptor, had created the cauldron which was supposed to hold the flame for the Games and serve as the event’s spiritual centrepiece. Its image will now grace one side of the 2020 coins, Lee-Sheriff says, noting that Walker was “interested in leaving a legacy with the coin.”

How much the coins will cost has yet to be determined, Lee-Sheriff says, and is influenced by casting fees. Ten per cent of the money derived from the sale of the coins will go to the AWG, to help fund future games, and coins will be available at a discounted price to the athletes and volunteers who were unable to attend this year’s Games due to the shutdown. “It was heartbreaking to see the Games cancelled,” Lee-Sheriff says. “Heartbreaking, but necessary…. I’d like (the coin) to be something good that comes out of COVID.”