Pangnirtung—the picturesque hamlet on Baffin Island most recently in the headlines after a powerplant fire spurred a month-long logistical miracle just to keep the lights on—might be the last place that comes to mind when you think tech start-up. But in 2012, Pinnguaq founder Ryan Oliver saw an opportunity to incorporate Inuit language, culture and stories into video games—a medium that entrances kids, but also generally follows the homogenous ‘white hero’ myth in its stories.

To accommodate its audience, Pinnguaq’s products would have to be custom-made for Nunavummiut in more ways than one.

Take its first app, Singuistics: Programmers came up with a fun way to let users practise their pronunciation of Inuktitut words by letting them sing along to traditional and contemporary songs by Inuit musicians before finally performing and sharing them with friends. But the unique—no, frustrating... no maddening—broadband situation played a factor in Singuistics’ design.

In fact, the territory’s slow Internet speed, unreliability and low data limits are considerations equal to that of the company's stated mandate of empowering Nunavummiut by embracing technology—and those connectivity issues factor into every single thing Oliver does.

“We would consistently go back to it, with the number one problem of just making it smaller so people can download it quickly,” he says. “A lot of the way we design is with this idea.” Make it smaller, more compact, easier to download. Singuistics doesn’t even require users to be online for it to function.

This broadband capacity also hampered the apps construction. Every two weeks, the software Singuistics was built in required an update roughly two gigabytes in size. In most Nunavut communities, two gigabytes can constitute up to one-fifth of a customer’s monthly data limit. “You can imagine, every two weeks, you’re getting a new two gigabyte update, which also takes an entire night to download,” he says.

Not only does that constrain the imagination, limiting the types of products Pinnguaq’s innovative team can dream up, it also stunts their ability to grow the business. “We’re competing in an industry that’s changing every single day and accelerating faster than every other industry,” he says. “It becomes really difficult to maintain an ability to be competitive when you simply can’t download what’s new in the world.”

“When you can’t even edit your own film [in the North], there’s an issue there.”

That’s why most of the actual software builds are now done in Vancouver, where internet reliability isn’t an issue and costs aren’t through the roof either. Oliver himself recently moved south to Ontario. Ninety-nine percent of that decision was made with his kids’ educations in mind, but it doesn’t hurt that he now pays $60 per month for what in Pang would have cost more than $1,000. “What Pinnguaq has been and what it can become is accelerated by the fact that I’m not dealing with those issues anymore,” he says.

Think about that: to promote Inuit culture more effectively, you have to leave the North. Oliver recounts the story of a filmmaker friend, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, who had to move to Montreal for two months to finish her last film. Files were too big to send back and forth between her editor in Montreal and her home in Iqaluit. “When you can’t even edit your own film [in the North], there’s an issue there.”

Broadband access is increasingly being recognized as a basic human right, and with good reason. It connects people; it can unify cultures. At a speech in Tromsø, Norway last September, Oliver spoke about how the Nunavut Hunting Stories of the Day Facebook page gives Inuit a platform to counter narratives about their hunting lifestyle, seen as offensive by some with a limited view of traditional practices. “It brought people to our front doors and allowed them to see first hand what was going on and how interwoven with the very fabric of daily life these animals and this tradition is in Nunavut. At the same time, looking inward, it has allowed Inuit from across Nunavut to share hunting traditions, to confirm with photographic and video evidence the stories of their elders and, more often than not, some great laughs.”

Reliable broadband also increases educational opportunities—especially for the curious, self-guided learner. It gives telehealth programs added reach into, and use in, remote communities. It quickens the pace and reduces the cost of information-sharing for governments, regulatory agencies, research institutions and businesses. And it even creates brand new businesses and industries.

But funding telecommunications infrastructure isn’t often considered on the same level as more traditional nation-building projects like road construction or airports. As infrastructure-deficient governments concentrate economic development in a few locations spread across the vast North, these projects will still be obliged to use telecommunications systems that struggle with capacity and reliability.

If the digital age is characterized by the instantaneous flow of information, the North is getting just a trickle. In fact, if service doesn’t improve by the end of the year, much of Nunavut’s broadband could be in contravention of CRTC targets. In 2011, the federal telecoms regulator called for minimum levels of 5 megabits-per-second by the end of 2015. That’s not yet the standard.

As it stands, all 25 of Nunavut’s communities are served by satellite. The maximum speed available is 5 megabits-per-second, currently offered to Iqaluit customers and to businesses in Cambridge Bay, Arviat and Rankin Inlet by Northwestel. The rest of the territory has access to 2.5 mbps speeds through Qiniq, owned by SSI Micro.

Less than one-third of NWT communities are connected to southern Canada via fibre optic cable, with the rest of the communities—and the territory’s diamond mines—served by microwave transmission towers or satellite. All of the Yukon is served by either fibre or microwave, except Old Crow.

Prices are prohibitive. (See above.) And the satellite network presents obvious issues with reliability and redundancy (or a lack of back-up) as evidenced by Telesat’s Anik F2 satellite malfunction on October 6, 2011. It shut down Nunavut, 10 NWT communities and Old Crow for 16 hours. Planes were grounded. People couldn’t pay for goods with debit or credit cards. Long-distance calls were impossible.

The North’s telecoms situation is anything but static. Northwestel began a five-year, $233 million modernization plan in 2013 to improve internet speeds and provide cell service to 99 per cent of Northerners. And the CRTC just launched a review in April to ensure all Canadians have access to “world-class telecommunications.” Part of these proceedings will determine whether its previously established target of 5mbps is still adequate. (Remember, much of the North doesn’t yet have that capacity.) The CRTC is also looking at satellite company Telesat’s price ceiling and whether it’s still appropriate. Telesat is the Nunavut satellite “backbone” and internet providers like Northwestel and SSI Micro in Nunavut have to buy space to provide their services.

A 2014 study, Northern Connectivity, with representation from the military and territorial and federal governments, looked at the government investment required to improve internet delivery with a target of 9mbps, based on what bandwidth needs might be in the near future. (We do watch a lot more video now than we did four or five years ago.) The study’s findings raised some eyebrows. The required investment ranged from $622 million to add capacity to the Northern system but no redundancy, to more than $2 billion with a full network back-up.

That’s a lot before even comparing that 9mbps goal with the plans of the Finnish government and an Alaskan task force, which have set baseline targets of 100mbps for 2015 and 2020 respectively. The Northern Connectivity study found average speeds for satellite and microwave users in Yukon and NWT were 2.6 mbps and 1.5 mbps in Nunavut. Oliver tested his internet speed while in Tromsø—the same latitude as Pond Inlet—and he was getting 90mbps. “In Nunavut, you get about one [mbps.],” he says. “I run speed tests on occasion and I don’t think I’ve ever seen it go over 1.5 mbps.”

Companies will tell you it’s hard to make money while investing in telecommunications infrastructure in the North, where a small population is scattered across the remote corners of a huge wilderness.

They’re right. It’s clear any big change will need government support.

The good news is, in some places, that support is on the way.

Like a 1,154-kilometre fibre optic line along the Mackenzie Valley to Inuvik (and eventually Tuktoyaktuk) that will connect seven NWT communities to the south. The $82-million project, funded by the territorial government, is more than one-third done and could go into operation shortly after its expected completion date of September 2016.

It’s already providing a boost to Inuvik’s burgeoning satellite tracking industry. The Inuvik Satellite Station Facility makes the most of the town’s location, above the Arctic Circle, and the relatively low radio-frequency interference it produces, compared to larger centres. Ground antennae track polar-orbiting satellites, which pass overhead 10 to 11 times a day for between 10 to 15 minutes at a time, and receive data transmissions that include an array of Earth-monitoring information from weather to vegetation data, which is then sent to the satellite’s owners.

The Swedish Space Corporation announced in January it was building a second 13-metre antenna in Inuvik—“these are very large, they’re roughly the size of a four-story house,” says Tom Pirrone, the corporation’s global business development VP. The fibre optic line will help them transmit information quicker. The majority of data is sent to clients via microwave transmission, but due to the volume, in some cases, information is burned onto CDs that are shipped in the mail, says Pirrone. The company’s commitment to the line as a customer helped the government make the business case for the project.

Out west, the Yukon government continues to mull over the idea of connecting to an Alaskan fibre line to provide redundancy to its one Whitehorse connection. It’s a no-brainer to Whitehorse-based consultant (and Up Here Business columnist) Keith Halliday. “You could have Internet-based businesses. You could have data centres like Facebook has in Northern Sweden, where the cold air cools the servers. You could have more people that do business on the Internet that wouldn’t have their entire businesses at risk of being disrupted by [a cut to] the single cable.” (That happened on September 29, 2014. The line to Yukon was cut somewhere in B.C., causing service disruption for 12 hours. It’s not the first time it’s happened, either.)

An Alaskan company just announced it will extend a fibre optic line from Juneau to Skagway, bringing it that much closer to the Yukon. Connecting it to Whitehorse is “$25 million out of a $1.3 billion budget,” says Halliday. “Just pull the trigger on that. Stop talking about it and get it done.”

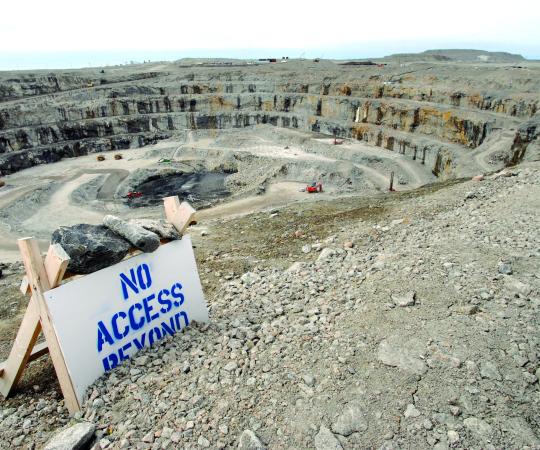

Then there’s the mammoth project that’s captured the imagination of many Northerners: a proposed $620-million 1,500-kilometre fibre optic cable project from Tokyo to London, buried below the Northwest Passage. The Arctic Fibre project would connect to seven Nunavut communities initially—and potentially 23 of 25 with some government support—along with towns and resource development projects in Alaska, Nunavik and Northern Labrador.

“When Arctic Fibre was making its own submission to the Nunavut Impact Review Board, it actually had to send its digital files by mail ... the files were too large.”

As the team was finalizing its project application to Nunavut’s regulatory agency, it came face-to-face with the very reason it was being put forward. “When Arctic Fibre was making its own submission to the Nunavut Impact Review Board, it actually had to send its digital files by mail,” says Madeleine Redfern, a consultant for the company and former mayor of Iqaluit, because the files were too large. (Ryan Barry, NIRB executive director, says it’s true, the board asks for 1GB-and-bigger files through the mail, so it has a hard copy. It also uploads most of its documents in Yellowknife, where speeds are faster.)

Arctic Fibre has yet to line up a partner in Canada. The federal government announced $305 million in funding to connect rural and remote Canadians, but that money will go into increasing satellite capacity—a requirement of the funding is that it be devoted towards improving service immediately. “More and more applications are requiring more broadband and there’s a growing number of users,” says Redfern. “Even with the same level of investment, we’re falling further and further behind.”

Redfern hopes the government will at the very least fund the construction of 16 hook-up stations—at a cost of $16 million—which must be installed during the first phase of construction. If not, the dream of connecting Nunavut (and Nunavik) will be buried along with the line. The cost to build spur lines to connect the remaining communities later on would be $250 million—a figure that’s a few years old—but if just the initial branching units were built, it would give future governments the opportunity to continue with the project.

Part of the problem, says Redfern, is telecommunications are an out-of-sight, out-of-mind issue for the federal government. “If it’s not burning down, like the powerplant in Pangnirtung, it doesn’t matter.” All levels of government and Inuit organizations need to get together to combine forces, she says. “We all have a limited amount of resources, but combined, some significant initiatives could be undertaken to really improve people’s lives,” she says. The line can connect to the $188 million Canadian High Arctic Research Station being built in Cambridge Bay; it can help monitor traffic and conditions in the Northwest Passage; it can ensure there’s more broadband for emergency response. When the plane went down in Resolute Bay in 2011, the RCMP went on CBC, to plead with people not to use their telephones so that they could communicate with the first responders from Iqaluit to Resolute, says Redfern. “It doesn’t take much for our system to get jammed.”

Oliver wants the fibre line too. It’s not just the military, tech companies and governments hampered by the lack of capacity; it hurts attempts to build small, local economies. Before starting Pinnquag, Oliver was senior advisor for culture with the Government of Nunavut. His job was to figure out how to get artists online, to create a venue to sell their goods outside the territory. “The issues were way bigger than just bandwidth,” he says, alluding to a lack of access to technical equipment and know-how involved with website building and maintenance. “That’s an area that’s just as important as Nunavut develops its bandwidth capacity, to also build the educational capacity to handle things as they catch up.”

Pinnguaq has started a Nunavut coding club, giving kids across the territory a chance to create their own games while building computer science skills in the process. But Oliver says the shortage in local computer proficiency is a chicken-and-egg scenario: “It’s a step forward not taken by a lot of people because it’s kind of like, what’s the point?” Oliver was self-taught down south to a great extent, able to pick up countless technical and programming tips from YouTube tutorials. “You can’t load up a YouTube video,” he says. “You would destroy your bandwidth in a couple of days if you sat and really tried to learn the way you can [in the south.]”

It all starts with bandwidth, he says: “If we had better bandwidth, we’d have better education because even if people weren’t getting it in school, they could teach themselves online.”

The information age is in its infancy in the North. But as techies continue to move to Whitehorse to enjoy the rugged, outdoorsy lifestyle the Yukon offers, and new connections strengthen a growing high-tech industry in the Mackenzie Delta, who’s to say that beautiful Pangnirtung can’t become the North’s answer to Silicon Valley.

It could be possible. With just a little imagination.