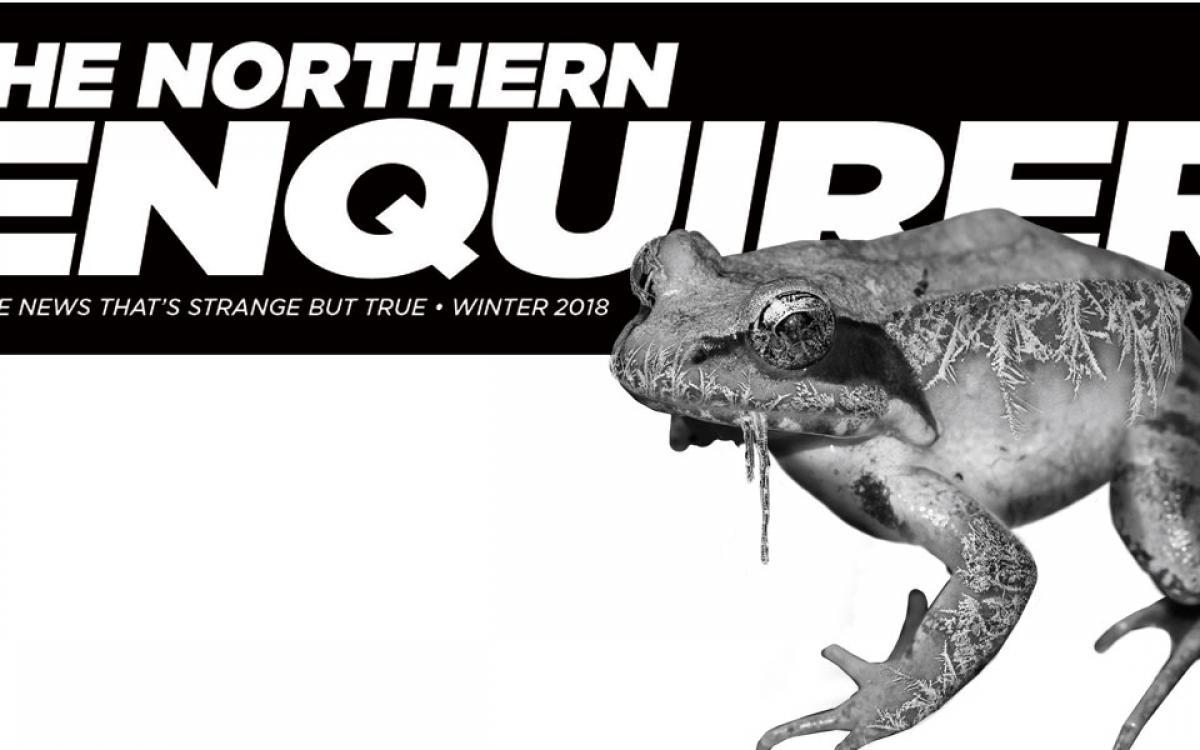

It’s the dead of winter and the wood frog has no heartbeat, no brain activity. Covered in ice and frozen nearly solid, it waits for its time to RISE FROM NEAR-DEATH—or rather, to defrost.

“They look like they’re totally dead, and then they’re not,” says Janet Storey, a research associate at the Institute of Biochemistry at Carleton University. Her lab is one of just a handful around the globe studying these cryo-frogs. Up to 70 percent of the wood frog’s body freezes in the winter. But unlike other creatures, their cells don’t burst like frozen pipes. Instead, they draw most of their body water into the abdominal cavity and between their skin and muscle. That means ice forms there and not inside actual blood vessels, where it can cause potentially fatal damage. Storey says wood frogs also limit the total amount of ice that forms in cells by using sugar and salt to trick the cells into expelling water. “The cells go, ‘Holy crap, it’s way too salty outside!’” she says, which causes the cells to dehydrate.

The cold-blooded wood frog lives further north than any other amphibian in North America, reaching into the Mackenzie Delta in northern NWT. Their powers of regeneration are one of the main reasons they’re as prolific as they are. And as the planet’s climate changes, these adaptable creatures are spreading even farther north.

Is there something we can learn from the wood frog? Is there a way they can help our species increase our odds of survival in frigid climates or perhaps even one day colonize a faraway frozen planet?

Currently, individual human cells can be frozen, as well as “anything that’s really thin and flat” like human corneas, skin and heart valves, says Storey. But anything bigger tends to not do well in a deep freeze. “So far there’s nobody that’s been able to freeze an entire organ and get it to survive and function when it comes back.”

Studying the frogs could change all that. Still, the manphibian (a cold-immune human-wood frog cross) remains within the domain of science fiction. At least for now.