The final moments of a snowshoe hare’s life are rarely pleasant. Scientists already know that most hares in the Yukon die from predation. Now, thanks to mini microphones installed on lynx tracking collars, they know exactly what the hare sounds like in its death throes. First, both animals crash frantically over low shrubs. Then there’s a brief, puzzling hush. Suddenly, the hare lets out a short, blood-curdling scream. The hunt is over. “It almost sounds like a person chewing an ice cube,” says Allyson Menzies, a PhD student from McGill University, describing a lynx crushing the bones of its prey.

The microphones Menzies and her colleagues have attached to lynx record and store audio 24 hours a day for up to two weeks, capturing the sounds of hunting, grooming—maybe even mating. The audio project is one of several hare-lynx studies underway in southwest Yukon this winter and spring. Menzies and four other researchers are based out of “Squirrel Camp,” a cluster of brightly painted ramshackle buildings off the Alaska Highway, partway between Haines Junction and Kluane Lake. Squirrel Camp has long been a summer base for red squirrel research, but now lynx and hare researchers move in for the winter.

This predator-prey duo has been studied in the Kluane area longer than anywhere else in Canada, and for good reason. The snowshoe hare is, in science lingo, a keystone species. Without a healthy hare cycle, the entire animal kingdom of the boreal forest would be in jeopardy—and climate change is putting this cycle at risk. This past winter, lynx and hare were near the top of their 10-year population cycles—the prime time for gathering data. And this time around, researchers are equipped with new gadgets that have allowed them to capture data they couldn’t have dreamed of getting just a couple decades ago.

Michael Peers from the University of Alberta is driving around with a radio antenna, trying to determine if any of his collared hares have died. When a hare doesn’t move for a certain length of time, a “mortality switch” goes off on its collar. Peers hurries to the kill site to collect the expensive and valuable data-filled collar before it gets carried away by scavengers.

Peers is researching coat mismatches: when a white bunny sticks out like a beacon against a backdrop of green foliage because it hasn’t grown its brown summer coat yet. “As climate change decreases the number of days with snow on the ground, we get more and more days where the hare are mismatched,” he says. This puts hares more at risk for predation. Scientists believe coat change is caused by length of daylight and the hormone melatonin that comes from the sun. “It’s not necessarily a thing where the hare is making a cognitive decision: ‘Look at my environment, I’ll adjust the way my coat changes,’” Peers explains.

This spring, Peers is setting up two hare enclosures—one with snow and one without—to study if reflection off the snow can affect coat change rates.

Most days between November and April, Menzies is out in the bush live-trapping and collaring lynx or tracking them on foot using GPS. At -30 C, it’s too cold for live trapping, so Menzies settles into a worn couch next to a wood stove in the cluttered, cosy kitchen building at Squirrel Camp.

“It seems to be pretty crappy to be a bunny,” she says. “Everything’s trying to kill you.” While almost every boreal forest predator eats hare—from wolves to wolverine to birds of prey—only the lynx is a true specialist. Historic fur trade records have allowed scientists to trace Canadian lynx and hare populations back more than 200 years, confirming the predator-prey cycle that is described in most university-level ecology books: the lynx population trails the highs and lows of the hare population by about a year. The populations of both animals peak and crash every 10 years or so. The changes are drastic—the hare population can increase 25-fold at its apex.

But lynx do not determine hare populations on their own. “Hares aren’t just affected by lynx and coyotes and goshawks and owls killing them,” explains Menzies. “They’re affected by the fact that there are predators everywhere and the hares are getting really stressed and they’re stopping reproducing.”

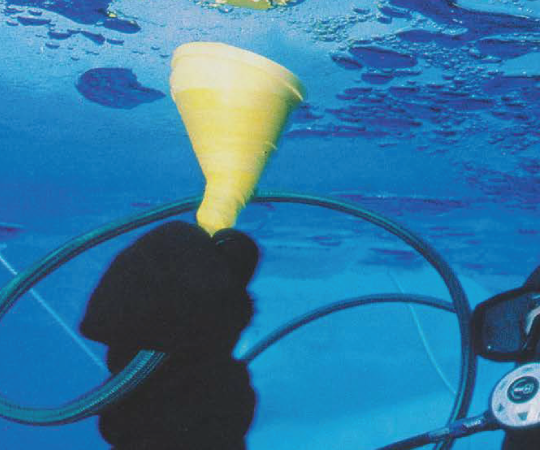

New technology is helping researchers identify habits among hares and lynx. Menzies is putting accelerometers on lynx and hare collars that use similar technology to Fitbits. They track movement in three planes: side to side, up and down and forward and back.

It’s not always easy to tell what an animal is doing just by sound or movement, but Menzies’ hope is that by calibrating the microphone and accelerometer data, they might paint a clearer picture. With the click of a mouse, scientists would be able to determine exactly what a lynx is doing over a 24-hour period and how much time it’s devoting to each activity—answering questions like how much energy lynx expend in a day and how many hares they must eat to survive?

In addition to feeding numerous predators, hare take hunting pressures off other plant-eating animals like ptarmigan, ground squirrels and even lambs. “Ecosystem Dynamics of the Boreal Forest,” a research book nicknamed the “Kluane Bible” by Squirrel Campers because of its ubiquitous use, notes if hare populations were to disappear, other animal populations in the boreal forest would largely collapse, spelling all sorts of chaos.

The Kluane Bible isn’t new. Published in 2001, it outlines snowshoe hare research collected in the Kluane area between 1986 and 1996 by many scientists who are still involved in the project. Menzies’ cohort is building on their work. “A lot of people say ‘Haven’t you figured that out already? There’s a book about it,’” she laughs. “We’re still asking the same questions they asked, just more in-depth or with better technology.”

Menzies and her colleagues joke about writing the next edition of the Kluane Bible. But as the original authors begin to retire, there is a certain pressure to continue the work they started.

“It’s kind of fun to be the next wave,” she says, aware the study is hers to continue.