Sitting in a high-rise apartment in the smog-clogged skyline of Beijing, a woman’s face is aglow from the tablet on her lap as she swipes through digital images of faraway, almost alien landscapes. She browses Norway’s dramatic fiords, Iceland’s endless lava fields, the barren, jagged rock faces on Nunavut’s Baffin Island.

The pictures pitch the simple promises of silence and clean air, but also the exotic: vast woodlands or tundra, aurora-filled night skies, caribou, polar bears, icebergs and glaciers—none of which she has a hope seeing at her current latitude. None of which her friends have ever seen. But what part of that Arctic world will she pick?

“People come up with a bucket list. I think both Alaska and probably Canada come up on both of those lists."

To understand Arctic tourists, you first need to know where they’re coming from. They’re generally mid- to upper-class people from wealthier nations—like Germany and Japan. They’re often from bigger cities and are looking to visit what they consider the planet’s last, unspoiled frontier.

When it comes to Northern destinations, the curious traveller has plenty to choose from. Alaska, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia and Canada are each rich with their own languages, customs and cultures. But to potential visitors, they offer many of the same things—Northern Lights watching, pristine landscapes and wildlife viewing—which makes it difficult for one region to stand out from the pack.

For Kathy Dunn, Alaskan tourism and marketing manager, it’s about getting that message out first. Her office is essentially responsible for ensuring that whenever someone’s considering travelling to a faraway, Northern destination, Alaska automatically comes to mind. “So we’re out there saying ‘Visit Alaska, this is why you should visit Alaska, these are the things to see and do,’ more of a broad message,” Dunn says. “Once we get that broad message out … people are thinking: ‘Oh, I think we’re going to go to Alaska this year.’ So then they go down to the community level and [start] looking at those websites and looking at who operates in that community.”

Of course it’s complicated—and expensive—to get that message out, but the consequences of not doing so can be devastating. Alaska promotes itself in five primary overseas markets: Australia, the U.K., Germany, Japan and Korea. Dunn knows people associate Alaska with glaciers, mountains and abundant wildlife, but the Yukon has all that too. If Alaska falters in its marketing to Australia, say, the Yukon could slide in and become that Northern archetype. The next time an Australian thinks about a glacier, ‘the Yukon’ might enter their brain instead of Alaska—and over time that could translate into millions of dollars of lost tourism revenue.

But Alaska is fortunate—it already has a solid base. The state recently broke the two-million-visitor mark last year, and only 10 percent of its tourists are coming from overseas. Fascinated Americans from the Lower 48, who grew up learning about Alaska in geography class, keep showing up in droves.

“People come up with a bucket list. I think both Alaska and probably Canada come up on both of those lists,” says Dunn. “People think of Alaska as the last frontier … There were a lot of people who grew up learning about Alaska, and thought one day: ‘Gosh, I’d like to get there.’”

The woman in Beijing wants to see the Northern Lights. ‘Who has the best aurora?’ she Googles. The search results are confusing.

All sorts of countries have aurora, but which is the best is a matter for debate. Dunn says Fairbanks’ dry climate makes it a prime destination, compared to cloudy Iceland, where tourists go on “aurora hunting” tours with little expectation of seeing the lights. Yellowknife has a similar climate to Fairbanks, and markets itself as the best aurora destination on the planet, with its position under the Aurora belt—the same circumpolar belt that Kiruna, Sweden, with its Aurora Sky Station, sits under.

She Googles prices, and the different ways to get to each destination. She discovers that she can see Alaska or Norway from a giant cruise ship—or Greenland and Nunavut from humbler ships with more expensive boarding passes. She can fly to Whitehorse or Yellowknife and, from there, pay much higher prices to visit the more remote communities, considered even further past that Northern frontier. Or she can travel to Nordic Europe, which is less remote, but allows for multiple ways of getting there and touring around—by train, car rental, or plane.

And here is a major factor that Northern jurisdictions can control to try to lure visitors: accessibility. Unfortunately for Canada’s cash-strapped and remote territories, this costs a lot of money. “Accessibility is a key issue for facilitating a successful tourism development. This makes places with good accessibility winners while places nearby may instead struggle to develop their tourism product,” says Dieter Müller, a professor of social and economic geography with a focus on Arctic tourism at Umeå University in Sweden.

It’s worth examining what tourism brings to Arctic nations in terms of revenue. For a place like Alaska, even the $1.9 billion the state generates annually through tourism is dwarfed by its oil industry. Nationally speaking, tourism revenues for Arctic nations are but a small—albeit dependable—source of revenue.

Müller believes expectations for tourism revenues in Arctic nations are often a bit high—especially considering the lack of accessibility and fierce competition between countries—but says it is often one of the few economic opportunities at the community level in Northern countries. Even though it doesn’t generate massive amounts of revenue everywhere, there are benefits felt in the small towns, villages and hamlets that don’t necessarily show up on the budget sheet.

“In a study we did in northern Sweden, we could show that even though a lot of the common indicators—employment, guest nights—pointed in a negative direction, locals were still satisfied with tourism development since it provided certain services, such as cafés, that were not available to the locals previously,” Müller says.

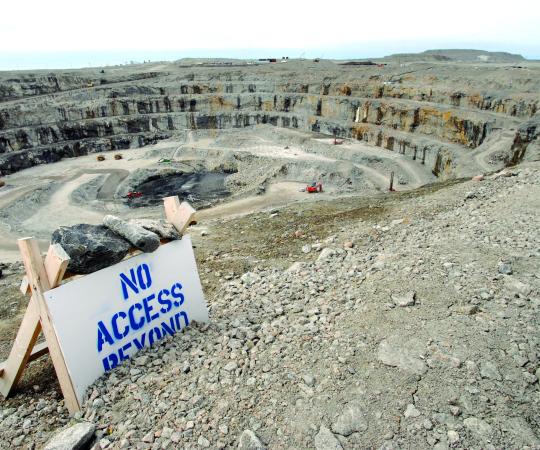

Tourism revenues can soften the blow from downturns in oil and other extractive industries, but if an area hasn’t had resource development, it often won’t have much transportation infrastructure in place, making it less accessible and more expensive for visitors. “Extractive industries are usually needed to justify the investment into the necessary infrastructure, and in particular transport infrastructure. Tourism is usually not potent enough to justify the establishment of airports, railroads, or roads. Hence tourism becomes a secondary user of that infrastructure,” says Müller.

Without proper infrastructure in place, Canada’s territories will find it difficult to compete with better-serviced places. As roads and airports are debated to support short-lived extractive projects, leaders would be wise to look at how that infrastructure could one day bring tourists, and their chequebooks, into their North.

The selfie-snapping, jet-setting brand of tourism is a relatively recent phenomenon in the North. We’ve always attracted sports fishers, hunters and other outdoor enthusiasts, but in recent years the numbers of sightseers has increased, specifically where air competition has increased and reduced fares.

Canada’s three territories have a particular advantage right now—the Canadian dollar is weak next to the American greenback, which makes it much cheaper for Americans and world-travellers to visit. The Yukon, perhaps sensing this, announced at the end of March that it would add another $2.7 million in funding to its marketing program, on top of the $3.6 million already earmarked from the federal and territorial governments—much of this money is going towards polished television advertisements. With budgets being cut in Alaska due to diminishing revenues from a paltry oil price, that investment could be more than Alaska’s entire tourism budget in the coming years. And that, combined with the Yukon’s cheaper flights and extensive roads, could be what the territory needs to put it top of mind in its competition for the hearts and minds of Arctic fanatics.

Meanwhile, a round-trip plane ticket from Tokyo to Yellowknife costs $1,700—and it’s more than twice that to fly from Tokyo to Iqaluit and back. The NWT and Nunavut could miss out on the spoils—even if they suddenly decide to spend millions on television commercials.