If you’re looking for Martha Black — “First Lady of the Yukon” and the second woman to be elected to Canada’s House of Commons — she’s not hard to find.

Just wander on down to the Whitehorse Pioneer Cemetery, where her well-polished, well-marked headstone sits gleaming in the sun on any bright Northern summer day, adorning her final resting place.

Well, maybe not the exact place…

While Whitehorse-based Yukon historian Helene Dobrowolsky says there has been “a lot of work done to pinpoint exactly where people might be located,” many of the grave markers in the 123-year-old burial ground were either laid down imperfectly or shifted with time, and it’s “entirely possible” that some of the headstones may be a bit off the mark. In large part, this is because the cemetery — now a well-manicured milestone of colonial culture in the heart of the Yukon’s capital — was not only unpopular with local residents in its day, but a municipal and territorial flashpoint.

Nestled against the clay cliffs near what is now the end of Main Street, many Yukoners of the day were dismayed by the placement of what was originally known as the Sixth Avenue Cemetery. When it was first assigned as a burial site in 1900 it was considered fairly out-of-the way, because in those days the population and commerce of Whitehorse was concentrated between First and Third Avenue, says Dobrowolsky. So much so that when the storied Hougen’s Variety store was moved from Second Avenue to Fourth — now a bustling commercial street — some people feared its business would suffer.

Whitehorse grew rapidly, however, and as the city expanded, some residents soon found the graveyard a bit too close for comfort.

H.M. Martin, a prominent Crown Timber and Land Agent, claimed the interred corpses would seep into the water table and contaminate well water. While Dobrowolsky says there has never been any evidence that the cemetery was (or could be) a health concern, in 1908 around 100 residents of Whitehorse signed an ultimately unsuccessful petition to have the cemetery moved due to these sanitation concerns.

“From day one [the cemetery] was a political hot-potato,” says Dobrowolsky. “The city of Whitehorse — which didn’t incorporate until 1950, as we know — refused any responsibility for [the] maintenance and care of the site. Technically, the cemetery was a territorial responsibility, but at that time the government was focused in Dawson City, and not terribly concerned with what was happening with a tiny graveyard in the backwaters of Whitehorse.”[1]

The bickering between the city and the territory over who was responsible for the site continued for decades, leaving the cemetery broken down and shabby. The city council settled on a community burial ground on Grey Mountain, and claimed the downtown Pioneer Cemetery was on territorial land, making it the Yukon government’s problem, while the territorial government argued just the opposite. By the 1960s the site had fallen into serious disrepair. Then, in 1965, many towns folk were outraged — some might even say barking mad — when the local funeral director had his beloved dog, Ginger, buried in the cemetery, complete with an elaborate headstone reading, “She Brought Sunshine To Our Home.”

While there’s no denying the Yukon is a dog lover’s paradise, Dobrowolsky says some were appalled by the idea of a dog being buried alongside people. Ginger’s monument was removed, and the dog was dug up and reburied elsewhere a few days later, but the kerfuffle brought further public attention to the deplorable condition of the Pioneer Cemetery.

The City of Whitehorse officially took over care of the site shortly thereafter, but the damage had been done; the cemetery was a decaying, overgrown mess, unkempt and speckled with cold-cracked tombstones and rotting crosses.

In the 1970s, a well-intentioned but poorly undertaken attempt at revitalizing the site led to some of these dilapidated crosses being thrown away, and with them the names, fates and placements of the people they memorialized.

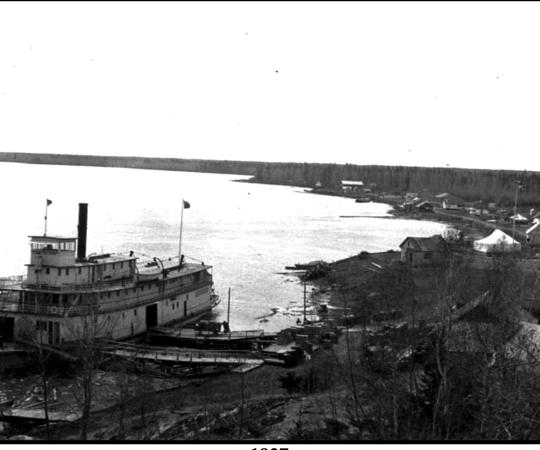

Among those mislaid was 52-year-old James Brown, reportedly the first to be buried at the site in 1900 after succumbing to pneumonia; and Blanche Beauchamp, who died in 1913 following complications from childbirth. There was also Timotheus Leonard, a waiter aboard the steamer ship Wilbur Crimmins, whose mysterious death in 1901 while docked in Whitehorse may have been the result of his penchant for sleepwalking.

Of those who remain with markers in the cemetery, we can count Anna Katrina (Lauridsen) Viaux, who became the owner of the White Pass Hotel after suing the man who owned it for backed wages after, having lived and worked with him for several years, he abruptly dropped her to marry another woman. There’s also Ralph Caruso, a railway worker moonlighting as a cab driver who was murdered in 1958 when he refused to drive a pair of drunken fares to Prince George, B.C.; and Martin Berrigan, who built the (in)famous three-story Whitehorse log cabin “Skyscrapers,” which is still standing today, having long outlived Berrigan, who died in 1950.

The cemetery was officially closed to burials in 1965, with an estimated 800 people entombed below the frost-bucked earth in the heart of Whitehorse, although a few many have been “snuck in on special dispensation” after that, says Dobrowolsky.

“There’re a lot of notable people here — [people from] the military, the RCMP, from various service groups,” says Dobrowolsky. “But there’re a lot of humble people here too.”