Selling sealskin by satellite

Inuit women are using social media to change the face of Nunavut business

Nothing demonstrates the ingenuity of Inuit seamstresses like baskets made from duck feet. Finding a use for every part of an animal, these resourceful artisans discovered the oily feet of the duck—or goose or loon—were perfect for keeping sinew (often caribou tendon, used as thread) pliable for sewing.

It’s one of Mona Netser’s favourite projects to teach her students. “It was just amazing how their faces lit up, that they can use [the basket] in their home and display it so their kids and their grandkids will start seeing these,” says Netser, an internationally recognized seamstress who travels throughout the Kivalliq region teaching traditional design with Nunavut Arctic College.

Just as inventive seamstresses from the past experimented and perfected their craft using furs, skins, bones and other items harvested from the land, today’s artists are finding clever ways to bring traditional clothing—or their contemporary takes on ancient designs—to market. Netser is one of hundreds of women in Nunavut using social media to sell unique products to buyers in the North, throughout Canada and internationally.

Her signature item is the sealskin leg warmer. It looks like the top of a kamik and can be placed over any pair of high heel shoes, covering the ankle and calf with sealskin. The warmers are popular in both Nunavut and southern Canada and clients almost exclusively use Facebook’s messenger function to contact Netser with their orders. “I get the measurements, like how high they want it and all that information,” she says. “I’ll ask them questions and what colour they want.”

Nowhere is the social media market more obvious than on the Iqaluit Auction Bids page, which is updated constantly with new items and boasts nearly 30,000 members. (The population of Iqaluit is less than 8,000.) A seller posts a description of an item, usually with a picture, along with a starting bid price and an auction deadline. Most items are handmade and range from entire polar bear skins and kamiit (sealskin boots) to artwork and tools. The auction takes place entirely on the Facebook page and participants bid back and forth until the clock runs out. The person with the highest bid wins. Payment is typically made via email money transfer so the seller can be paid instantly.

While Iqaluit Auction Bids has the most members, every community in the territory has its own version, usually in the form of a sell/swap page where sellers can negotiate directly with potential purchasers. And profits are quickly adding up. By using social media to connect with each other and the world, women are finding new ways to use traditional skills to earn an income.

Permanent long-term jobs are rare in Nunavut’s smaller communities. And even in communities with available jobs, the odds are stacked against women.

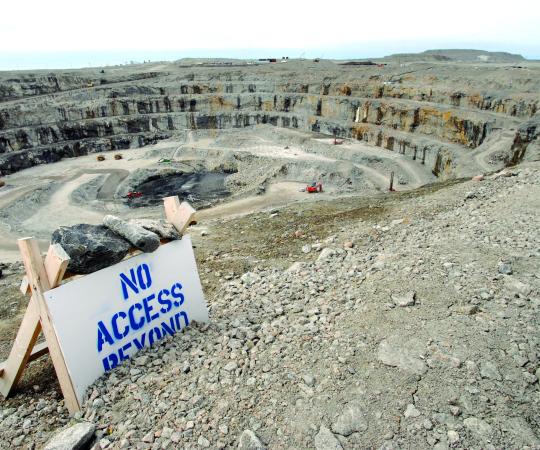

In 2014, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and the University of British Columbia published a study examining the impact of Agnico Eagle’s Meadowbank gold mine on women and families in nearby Baker Lake.

As of 2012, Inuit women made up nearly half of the mine’s 166 permanent Inuit workers. Though the majority of women held housekeeping and kitchen jobs, 14 out of 60 Inuit haul truck drivers were women by the end of 2012 and one of them had become an instructor. But the report noted that absenteeism at the mine was often as high as 23 percent. Without suitable childcare available in Baker Lake, women working at the mine were often at a disadvantage.

Many of the issues highlighted in the report, especially a lack of childcare, are facts of life for women in Nunavut communities. Developing traditional skills such as sewing means women can create income-generating businesses right in their own homes.

“Everybody is not going to get their college degrees or their school degree because we’re all different,” Netser says. “I love to encourage young mothers, young girls, that they can use their hands to create things and make a living and help with their family.”

A handmade amauti, a traditional coat with a pouch used to carry a baby, posted to a community sell/swap Facebook page can bring in anywhere from $300 to $700. A crocheted hat can fetch $25.

Because operating costs are minimal, social media is an ideal way for women in Nunavut to start new businesses or supplement their incomes, says Adina Tarralik Duffy, owner of Ugly Fish, a clothing and jewellery design company based in Coral Harbour, population 1,000.

“The overhead is low,” she says. “As long as you can afford [internet] then you can generate an income without travelling, without having a brick-and-mortar building.” Gone are the days when artists have to go door-to-door to sell their products. Today, they can simply post a photo and the item can be purchased instantly. “As soon as you upload a picture of, let’s say, a necklace or a pair of earrings, they could be gone within a minute,” Duffy says. “Sometimes I’m even hesitant to post online unless I’m ready to sell.”

With the exception of trade shows, all of Duffy’s business is now done through social media. “It’s so accessible. You can just take a photo and upload it. I have an Instagram following and a Facebook page. I find it easier to manage right now than having a website.”

Artists like Duffy are also coming up with fresh designs while still relying on traditional materials. Her leggings feature logos like those of Klik canned meat or pilot biscuits, easily recognized by anyone who has spent time at a cabin in Nunavut. Duffy and her partner Aaron Regnier also create jewellery from natural materials, such as seal claws and vertebrae. “There is just so much to be inspired by,” Duffy says.

Nicole Camphaug owes her business to a moment of inspiration. In 2015, while trying to figure out what to do with a grade of sealskin that was too thin for mitts, Camphaug decided to try applying the skin to a pair of stiletto heels. “I’d never seen any dress shoes or high heels or anything with sealskin and they just turned out so nice on that stiletto, I thought, ‘that’s another way to use our sealskin,’” she says.

Since then, Camphaug’s ENB Artisan (which runs under a Facebook page of the same name) has sold about 100 pairs of sealskin stilettos and dress shoes, which are quickly becoming the go-to fashion item for those wanting to publicly promote sealskin and Northern products. Nobel Peace Prize-nominee and Inuit activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier wore a pair to a talk she gave at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto last November and Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, the documentary filmmaker behind Angry Inuk, also wore a pair to a Toronto International Film Festival event.

Camphaug, originally from Rankin Inlet and now living in Iqaluit, says she wanted to learn sewing skills to be able to make her own clothing. “I wanted to be able to do those things myself so I didn’t have to rely on anybody else,” she says. Now, she’s finding that these new ways of showcasing sealskin is helping to educate people about the relationship between Inuit and seal hunting. “It’s been used by Inuit since there were Inuit,” she says. “It’s sustainable, it’s environmentally friendly—there are just so many different aspects of using sealskin. For us, it’s important because it’s a part of our culture.”

The European Union banned the import and trade of seal products in 2009, but an amendment was made in 2015 to allow the import of seal products hunted by indigenous people. Still, the damage was done. The demand for sealskin plummeted and so did public opinion.

For many Inuit designers, educating people about sealskin is simply a part of doing business. Barbara Akoak, owner of Inuk Barbie Designs, uses hashtags in her posts to provide links to information, such as #eatsealwearseal and #arnaq. (Arnaq is woman in Inuktitut).

Akoak, a jewellery maker who grew up in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, derives inspiration from her Inuinnaq and Netsilik ancestry.

“Just being Inuk, we all have art in our life,” she

says. “It was a part of our ancestors’ way of passing time or making protective amulets. It’s deeply a part of our culture to always be creating art.”⎦

Though most artists go the Facebook route to move their wares, there is a push to formalize the sales process. Akoak, for one, does most of her Canadian sales through Facebook and Instagram, but she uses Etsy for international customers in Greenland and Alaska. This is a move the Government of Nunavut is encouraging.

Etsy, an e-commerce website where sellers create personalized online stores, offers secure payment methods, including credit cards and Paypal. Facebook is the quickest way to make a sale, but there is nothing protecting either the buyer or seller from fraud. Incidents where sellers receive email money transfers but don’t send the product aren’t uncommon and because the exchange is considered a civil dispute between private parties, police are often unable to help. Etsy offers more protection to both artist and customer.

“It’s not used an awful lot for now in Nunavut, but we just thought of it as a potential interesting idea and platform for Nunavut artists to use, mainly because of the secured online payment that is offered,” says Anne-Cécile Grunenwald, senior advisor of cultural industries with the Department of Economic Development and Transportation. An Etsy workshop was a key component of the 2015 Nunavut Arts and Crafts Association’s Nunavut Arts Festival in Rankin Inlet.

There is limited data on how much revenue women are making through sales on social media, but Grunenwald says the majority of Facebook sales seem to be taking place between Nunavut residents. Platforms such as Etsy could significantly open up that market.

In the meantime, it’s clear the skills passed down from generation to generation are still as vital today—and in the future—as ever. “There’s not a lot of jobs up here, especially where I live right now in Coral Harbour,” Netser says. “It’s good that we keep our traditions alive. I’m very strong on tradition.” — Kassina Ryder

Free Pour Jenny's

Bitters from Whitehorse

Wild edibles harvested from the forests, marshes and meadows of the Yukon are the main ingredients in each bottle of Free Pour Jenny’s bitters. Bitters are concentrated flavour extracts from different sources (like roots, barks or leaves) in an alcohol solution that are added to cocktails to produce new flavours.

For owner Jennifer Tyldesley, making bitters was a blend of several different hobbies: gardening, foraging, cooking and tinkering in the kitchen with mixology.

She has nine regular flavours of bitters, with additional varieties showing up on her table at the farmers’ market in Whitehorse, depending on what grows that season—or if someone happens to drop off a bushel of something new.

Tyldesley sold her first bitters last November, after spending the summer harvesting and perfecting her recipes. Her favourite ingredient to work with is the spruce tip—easily plucked from boughs in the forest—because of the tart, resiney flavour that wakes you up.

Retiring from a career as a pilot to spend more time with her family, she now works a lot closer to home. After picking mint and cucumber from her garden or fireweed and high- and low-bush cranberries from beyond her property line, she heads straight to the kitchen to start her tincture. Depending on how long it takes for the alcohol to pull the flavour from each ingredient, it will be about a month before the bitters are bottled.

“People love locally distilled and brewed spirits and beer and more locally grown food,” says Tyldesley. “There’s so much talk about that up North with food security and being self-sufficient, so it’s really a great time.” Two Whitehorse bars and one in Dawson City stock her bitters, which are also available in Calgary at Vine Arts Wine and Spirits. She’s hoping to get into Vancouver too, but is hesitant to expand too much. Her kitchen is only so big. — Elaine Anselmi

Laughing Lichen

Wild products from the NWT

It only takes an hour outside with Amy Maund before you begin to realize there’s food just about everywhere. She passes out some green alder catkins she’s picked. “Just nibble the tip of it. It’s strong,” she cautions, explaining these tiny, scaled cones can be used as a black pepper substitute. We bite in and the similarity is uncanny.

We’re down a well-trodden path, the ground around us covered with tufts of lichen, heading to a small swampy lake near Laughing Lichen’s off-grid headquarters, a 40-minute drive from Yellowknife. Maund stops to point out the bright green sphagnum moss carpeting the forest floor. It can be used as gauze to treat wounds; Maund plans to pad her baby’s cloth diapers with the moss. She’s six-months pregnant on this, the first day of the spring harvest.

We’re collecting Labrador tea, which Maund uses in Laughing Lichen soaps, face scrubs and Bushman’s Aftershave. We find a patch in a shaded bog and start picking—only 25 percent at most from each plant, she says. “I want to keep everything happy and healthy.” This philosophy pervades every aspect of her growing business.

What began as Maund’s hobby while at university and on contract jobs in the forests of Northern B.C. is, seven years later, a company that employs two to three staff year-round and ten “wild crafters” each summer. They spend the days harvesting spruce tips and rose hips, teas and fireweed to be incorporated into the 50-plus-and growing product list. (A Labrador tea picker can make anywhere from $20 to $40 per hour.)

Maund follows the seasons, harvesting mushrooms in the fall, chaga and spruce gum in the winter, most everything else in the spring and summer. (The down-season—March and April—is when she experiments with new products.) Armed with bear spray, a bush knife and Kenai and Gotsa, her two fluffy “husky specials,” she does her picking in the mornings, before the sun saps her coveted plants of their essential oils and medicinal properties. Then she heads back to clean and dry her harvest.

Maund was almost a victim of her own success. She was getting by with the help of her spouse Ian—“a year-round unpaid full-time employee”—and friends and family. But her daily harvests were becoming a chore as she worked seven days a week, 14 hours a day. So, she decided to hire on some staff and scale up.

Still, she has to turn down some exciting—and potentially lucrative—offers. A brewery in Ontario recently asked her for two varieties of Labrador tea and crowberry for a beer it wanted to brew, but the quantity required would have wiped out her supply. Two chain supermarkets also want to carry her products, but that would necessitate the type of mass-production that runs counter to her philosophy.

Take chaga, the miracle anti-oxidant fad currently sweeping North America. She’s been selling it for years and could drop everything to focus on just that. Instead, she harvests it in Northern B.C. for a couple weeks each year, only taking one-third of what she sees. When she sells out, she sells out. “We’ll never be able to be a big company,” Maund says. “There’s only so much that you can harvest sustainably, right? But that’s good.”

As it stands, she takes orders through her online store and sends out products to her 37 wholesale partners—mainly health food stores, museum gift shops and tourism centres in B.C. and the NWT.

“Gold!” Maund exclaims, tongue-in-cheek, pulling a small hatchet from her bag to shave golden spruce sap into a ziplock bag. Spruce pitch salve—made from the substance—is used to treat skin irritations and she can barely keep up with orders from Hong Kong. Tourists visiting Yellowknife from Asia are bringing Laughing Lichen back with them and they can’t get enough of the natural products made from wild plants.

Word is spreading in Canada too and Maund is venturing out with new products. She’s making bear and bison poop-shaped soaps for the Calgary Zoo, with educational blurbs about how animal stool is important for spreading seeds. And the Museum of Nature, opening a permanent Arctic exhibit in Ottawa, has asked her for Northern ingredients for its in-house restaurant. She and Ian are also building a harvesting facility near Lindberg Landing in the Deh Cho, where she hopes to teach educational workshops and help develop ethical harvesting economies in communities.

Maund whistles for Kenai and Gotsa, coaxing them over with a wave of a bag of moose jerky. After their snack, we begin the loop back to her facility. “It doesn’t look very lush right now, but there’s tonnes of food here,” she says, as we wade into a patch of dead cattails that will soon regrow. Those shoots can be eaten, she says. “They taste like cucumber.” And the green pollen spike up top, when steamed, tastes like corn on the cob, “but it’s better for you,” says Maund. “It’s got more protein and nutrients in it.” We pass a pine tree. A layer of bark can be ground down into flour. (This could find its way onto the product list, Maund hints.)

Though she’s willing to try most anything, there’s one item you won’t soon find Maund using. There’s a peculiar object—like a cross between a pineapple and a pair of antlers—on the shore. “It looks like it’s from another planet,” says Jessie Olson, a full-time employee.

Turns out it’s a yellow pond lily root a muskrat has pulled out to snack on. Maund smiles and shakes her head. “I did a big harvest a couple of years ago by kayak and we were diving down and ripping these things out.” She took the lily roots home, boiled them and chopped them up to eat like French fries. “It was disgusting. Like, so nasty! I almost puked.”

She puts the lily root down and leaves it for the muskrat. –Herb Mathisen

Uasau Soap

Skincare products from Iqaluit

The Clarkes paid top price for 50 pounds of blubber from a bowhead whale, hunted outside Igloolik, Nunavut last year. “I mentioned it to an older fellow Inuk and he said to me, ‘I hope you at least got maqtaaq out of it,’” laughs Bernice Clarke, co-owner of Uasau Soap, a skincare line that uses all-natural ingredients, including a few from the sea. “But you know what, we’ve come across something by accident and it’s healing and good for your skin.”

Back in 2012, on her cousin’s suggestion, Bernice started making body butters to sell at a craft market in Iqaluit alongside her table of Mary Kay cosmetics. She handwrote labels, wrapped each item in antique-looking paper she’d soaked overnight in tea, and tied each package up with hemp. She sold out quickly. “I had found a market that people were already looking for,” says Bernice.

Her husband Justin

recommended branching into soap. She was skeptical about demand at first, but it’s quickly become the company’s main seller. And Uasau Soap was born—the name adapted from ‘to wash’ in Inuktitut: uasaq. “It’s Nunavut in a bar,” says Bernice.

The Clarkes work with flora from the tundra like sassafras and through another casual suggestion they found a key ingredient: whale oil. Now, Uasau has customers proclaiming the products—that use bowhead, beluga and narwhal—are healing their eczema, psoriasis and other skin conditions.

It’s also reintroducing something that was nearly lost. In the early 1900s, Scottish whalers decimated bowhead numbers, which led to limited hunting for most of the century and an all-out ban by the federal government in 1979. Many Inuit, like Bernice, grew up without knowing the taste or benefit of the whale that helped sustain their ancestors before. As the bowhead population recovered, the ban was lifted in 1996 and annual hunts were awarded to different Nunavut communities. Bernice says one elder teared up when he saw that bowhead whale was used in their soap. “It was taken from them and we’re taking it back,” says Bernice.

Uasau soaps are sold in Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet and Winnipeg and can be shipped all over Canada. Though they have hopes to get bigger, Justin says they don’t want to go too far, too fast and compromise a truly artisanal product. – EA

Michele Genest

Writer and cook in Whitehorse

You need only glance at Michele Genest’s calendar to gain an appreciation for the growing appetite for Northern cuisine—both in and outside of the North.

In March, the author of 2010’s national bestseller The Boreal Gourmet and 2014’s The Boreal Feast was in Vancouver, working with a local chef to build a Yukon-inspired menu to promote the territory as a culinary destination. When I speak with her in mid-May, she is busy collaborating on a cookbook on ancient grains and seeds; working as a consultant for a documentary film about a Dawsonite attempting to survive for a year on food sourced in and around the town; and planning a dinner for the much-publicized ‘Across the Top of Canada’ culinary tour. “I don’t ever get bored,” she says.

In a couple of days she’ll fly to Old Crow, Yukon for Caribou Days to cook with six women with whom she recently collaborated on a cookbook—Vadzaih: Cooking Caribou from Antler to Hoof. These women taught her traditional dishes like pemmican and head cheese, and Genest brought in contemporary recipes like caribou wonton soup, inspired by other cultural cuisines. There’s an exciting exchange of knowledge and techniques happening right now, she says, between people who grew up elsewhere with other cuisines and Northerners who have always used local ingredients.

Dried spruce tips top Genest’s focaccia bread; rose hip jam fills a traditional Bakewell tart; Labrador Tea infuses a panna cotta with flavour. “That’s kind of my approach—to start with a Northern herb or berry or meat or fish, think about what I want to do with it and then look for recipes that people have done with things that might not be Northern,” she says.

Based on the popularity of her books, she’s become one of the faces of this Northern food movement. But she says everything is based on the work of the North’s first peoples who discovered what was safe to eat, what was good to travel with, and how to preserve food over the winter. “We’re all working and living in a context of Indigenous knowledge that we’re all so much the beneficiaries of.” – HM

Uncle Berwyn's Yukon Birch Syrup

Birch syrup from the Yukon

There were only 13 days this year to tap birch syrup at Berwyn Larson’s camp, halfway between Mayo and Dawson City. Despite being one of the shorter

seasons he’s had since he began commercial production 13 years ago, his stand yielded 30 percent more sap than usual.

It was a busy two weeks. “You have to process the sap every day you collect or it makes a lower-quality product,” says Larson. “So I’d be up until 4 or 5 a.m. processing my sap for the day and then up again at 7 a.m. to collect.”

Larson hires on a crew of four people to help out through the harvest—each getting their own corner of the lot. He then personally delivers the syrup to businesses in Whitehorse and Dawson City.

Uncle Berwyn’s Yukon Birch Syrup has customers across the United States. A brewery in Denmark even uses his birch syrup in its beer. (Yukon Brewing also has a birch beer that makes use of his birch concentrate.) Just last year he shipped an order to a restaurant in Saudi Arabia. His birch syrup has now been to every continent—though Larson says his efforts on the business side are meagre. “I didn’t get into making birch syrup to be a salesperson or marketer. I did it because I wanted a life out in the bush.”

Larson was living on a mining claim, concocting an all-natural root beer when the search for a sweetener led him to birch trees. After learning to tap the trees in Alaska, Larson returned to the Yukon and hiked around until he found his favourite birch forest. He built a camp and now lives there with his wife and two daughters—as well as chickens, pigs and a few goats. Five years ago, his camp reached the 1,500-tree threshold, and he has no plans to go beyond it. “The motivation is to live the lifestyle you want to live,” says Berwyn. “Once you’re doing that, there’s no need to get any bigger.” – EA

Aurora Heat

Fur products from Fort Smith, NWT

Fur is the past, the present and the future for Brenda Dragon. Her father was a trapper and when his trapping partner retired, her mother stepped in to take on the role. As a kid in Fort Smith, NWT, Dragon and her siblings grew up wearing fur trapped by her father and sewn by her mother, who would add small scraps of fur inside their mitts.

With access to ample quantities of fur, Dragon began giving out her little pieces of fur as warming gifts. When her friends came back asking for more, she started to think there might be a market out there.

That was less than two years ago. Today, Aurora Heat warmers are flying off the shelves. You slide the sheared beaver fur insert into your boot and place it on top of your toes (or inside your mittens) and the insulating layer traps in your own body heat. “It breathes. It’s natural. It’s durable,” says Dragon. “The Arctic Energy Alliance used their infrared camera and it actually demonstrated a 12- to 15-degree capture of heat.” Not only that, but the soft, plush fur also adds a layer of comfort.

Dragon sells Aurora Heat online, at retail outlets in all three territories as well as in Banff and Whistler. “One of the best things about Aurora Heat is the replacement of other disposable products,” she says. Battery-operated and single-use warmers are not renewable and sustainable like fur.

Aurora Heat has been a big hit with tourists, who keep their toes and fingers toasty while out in the cold watching the aurora. And they get the bonus of bringing home an authentic, handmade souvenir from the North. But the warmers are also catching on with locals, who are oftentimes being reintroduced to the warming and pleasing tactile properties of fur.

Dragon will be adding new products and also targeting new markets and demographics. (She’s been primarily focused on women.) And there’s a reason for this—her fur warmers are so durable, her customers don’t need to come back for a very long time. – HM