In 2017, the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) will celebrate its 100th anniversary. Also in 2017, Yukon College hopes to start offering its first bachelor’s degree, a three-year program in indigenous governance. It’s a significant step in its quest to attain university status. What’s the ETA? At the earliest, 2020, says Yukon College president Karen Barnes. Barring any miracles in the NWT and Nunavut, it will be Canada’s first university north of 60.

Yukon University’s goal, says Barnes, is to become a leading institution in indigenous governance, natural resources management, and climate change research. But there’s much more that comes with being a university.

Just look at UAF. Originally known as the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, the university has expanded its programs over the past century to include

everything from film studies and anthropology to a PhD program in natural resources and sustainability. It’s also aiming to strengthen its indigenous studies program, with special emphasis on the revitalization of Alaska Native cultures and the preservation of indigenous languages.

At the same time, it’s working to encourage higher student enrollment from Alaska Native communities. Ten years ago, says university provost Susan Henrichs, only four of the university’s PhD students were from Alaska Native communities. “Now, we’ve had a couple dozen graduates,” she says. “We have an additional 30 to 40 people enrolled in our doctoral programs who will soon be fully qualified researchers.”

That’s a dream scenario for Yukon College. “Repeatedly we get southern researchers and policymakers coming up and being the experts, and yet they haven’t lived here; they haven’t understood the North,” says Barnes. While they might employ local assistants or technicians and consult community members, they’re still framing their research questions and designing their methodology. Having a university in the North would help change that, says Barnes. “That doesn’t mean southern researchers won’t come up and do the research here,” she says. “But at least we’ll have the opportunity to inform them better.”

Having a university pays off in other ways: federal funding for research grants generate economic activity, says UAF’s Henrichs.

Alumni also tend to stay in the area after graduating. If you look around at businesses in Fairbanks and much of rural Alaska, she says, “you’ll find lots and lots of UAF graduates at the head of those companies.”

Yukon College is already looking outside for ideas. It’s a founding member of the University of the Arctic, a collaborative network of universities that offer Northern-focused programs or are based in the North. It has also started delivering programs in high demand elsewhere. Institutions in Sweden and Norway have expressed interest in the college’s Northern Climate Exchange, a program that sends students to study climate change impact in Yukon communities.

And what of its neighbouring territories? “I think it’s important to note that the three colleges [Yukon College, the NWT’s Aurora College, and Nunavut Arctic College] work very closely together,” says Barnes. Even though there are vast differences between the three territories, she says, they can be celebrated and reflected with a Northern university.

Around the North

The University of Tromø has six campuses across northern Norway, and offers graduate-level programs in both Norwegian and English. Its suite of programs include a one-year diploma to train as an Arctic nature guide, a bachelor’s degree in Arctic tourism, and a master’s degree in Governance and Entrepreneurship in Indigenous and Northern Areas. Its main campus has helped turn the port city of Tromsø, population 72,000, into a bustling, trendy university town, hosting a number of international Arctic-related conferences every year. (It probably helps that Tromsø is also home to the Arctic Council headquarters.)

Farther south, at the Sámi University College in Kautokeino, Norway, a hub of indigenous Sámi culture, students can opt for courses in subjects such as reindeer husbandry and Sámi history. They can also pursue a degree in duodji—traditional Sámi handicrafts and design—or study education programs in the Sámi language. These graduates can then go on to teach primary and secondary school with a culturally appropriate curriculum.

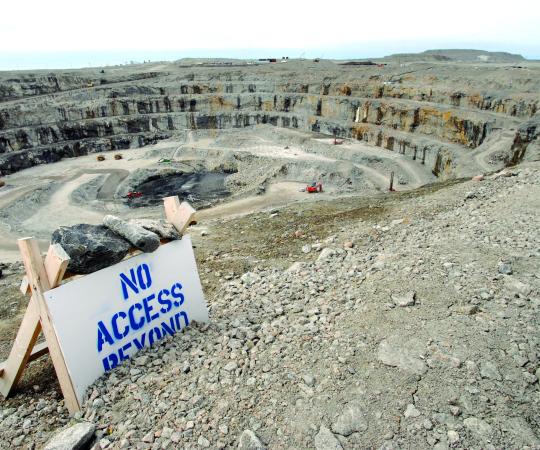

Over in Russia, Murmansk Arctic State University, housed in the largest city north of the Arctic Circle, places its focus on mining and engineering, training future generations for careers in the oil and gas industry.