By the mid-20th century, small trading posts were scattered along the coasts and major rivers of the entire Canadian Arctic. Most were Hudson’s Bay Company posts, although others had been established by the North West Company, Canalaska Trading Company, Revillon Frères, Russian-American Company, and private traders.

It was a time of tremendous change for the North’s first peoples, including the Inuit. Until then, they had lived entirely on the land, making use of stones, bones, skins, snow, and other resources to build their homes, and to fashion their winter clothing and hunting and transportation implements. Now, all of a sudden, they encountered imported goods, a trade and currency system, radio communications, and other inventions totally new to them.

Layered over these changes was a world at war, the Great Depression, and increased access by ship and aircraft to a huge and isolated land. The development of the DEW (Distant Early Warning) Line system following World War II would bring an influx of American military personnel and growing government involvement. New government services and regulations would impact life in the North forever.

While outsiders arrived with new goods and technologies, they also brought diseases like smallpox, tuberculosis, measles, influenza, diphtheria and sexually-transmitted infections into a population that had no resistance. Many people died.

Although focusing on one specific post could never stand in for the overall story of this era, a history of the Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts in Bathurst Inlet provides a general understanding of how the fur trade altered the local way of life.

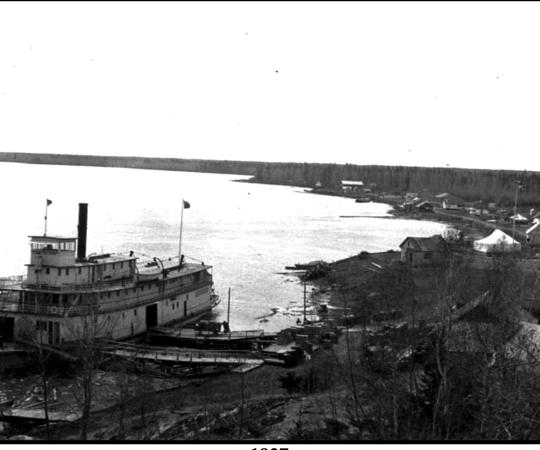

The series of Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts called the Bathurst Inlet Post were first established in 1925, and moved to different points in the inlet. Small ships supplied the post during the open-water season, bringing goods in and taking furs out. During the winter, almost everyone travelled by dog team from isolated small camps to trade at the various posts.

The HBC posts were located with an eye to competition from the Canalaska Trading Company (which the HBC traders called “the Opposition”), and private traders, who sometimes worked out of small ships frozen in for the winter. Traders built their posts where they could easily be accessed by people travelling from inland to the coast and their winter camps. At one point in the late 1930s, the Bathurst Inlet Post’s journal notes, more than 100 people were camped at the post.

The small community of Bathurst Inlet grew up around an HBC post. The company bought buildings from Dominion Explorers, a mining exploration company. The HBC moved

disassembled buildings and modified existing ones to create a store, staff house, fur warehouse, and workshop. Posts were located to take advantage of the movement of Inuit groups through the seasons, making it more likely that they would bring their furs to a particular post.

The little posts were usually manned by a couple of traders, along with one or two other staff who handled the intake of furs and the exchange of goods for fur. These post servants were almost always young men, often coming from Scotland. They travelled to Canada by ship and then by rail and riverboat to the North, and finally across the coast and into the Arctic by the small ships that serviced the posts. Many grew up on farms, and were often skilled with animals, carpentry, boats, and sometimes fishing. They learned other skills—housekeeping, cooking, working with furs and keeping records of sales—on the job. Most served for three to five years without a break, unless they needed to go south for health reasons. After WWII, it was common for a trader to be accompanied by his wife, but before 1950 that was rare.

Local Inuit also worked for the HBC and lived at least part of the year around the post, helping to process furs and maintain buildings, boats and dog teams. Many ran traplines themselves. They might live in snow houses in winter and dwellings they constructed themselves during other seasons. They were less nomadic than other Inuit residents, who ran long traplines and traded into the post.

The head trader was required to keep a daily journal, which documented the local temperature, weather, and the comings and goings of people trading at the post. They also noted wildlife movements, the results of hunting and fishing forays to supply the post, and activities to maintain buildings, boats, and other equipment. (Many journals include good records of the numbers of nets set and fish caught.) Journals also included details on the arrivals of inspection parties, supply ships, RCMP patrols, and later aircraft. The post could be a busy place.

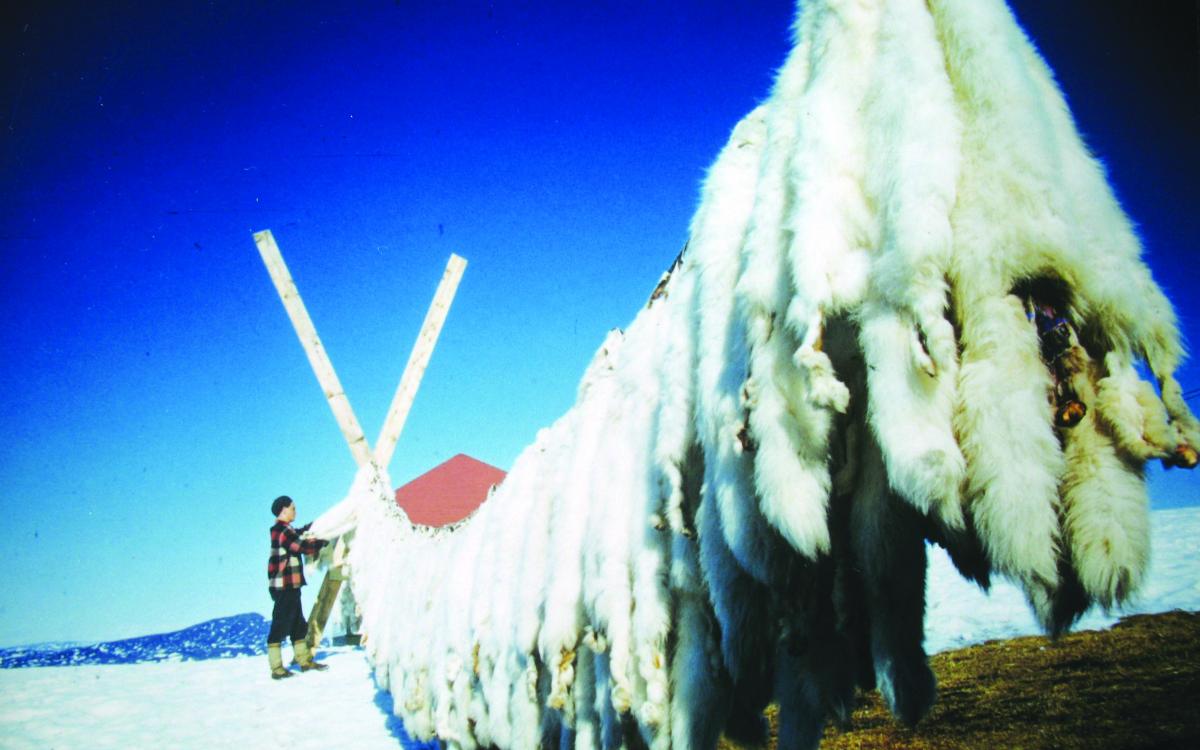

Beaver fur brought the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada, but it was the Arctic fox that stimulated the expansion of trading posts into the Arctic. Red foxes, wolves, wolverines, and even the occasional bear (polar or grizzly) were traded, as were ermine and seal skins. Although most traders hunted and ran their own fish nets, they were often short of fresh meat in their diets. Caribou, ptarmigan, geese, and Arctic hare were hunted or traded.

In the Central Arctic, Inuit hunted caribou at inland lakes and river crossings in the fall, when the animal’s skins were dark brown and ideal for clothing. They brought the caribou to posts when travelling back to the coast to overwinter in areas where they could access seals. These caribou skins were seldom sent south. Instead, they were almost always sent to other Arctic posts where caribou were scarce in the fall. From Bathurst Inlet, caribou skins went to posts in the Boothia Peninsula area to be used by local Inuit for clothing.

Furs were accepted only when prime—or when the fur was thickest. This meant when Arctic fox furs had fully changed to their winter white, which usually occurred by December.

Trading was a thoroughly commercial endeavour, with items of value to the trading company (furs) exchanged for items of value to the trapper and his family. Currency was not used, as it had no value to people as isolated from other commerce centres as the Inuit of the Central Arctic at the time. The HBC developed its own system of keeping track of barter. Wooden tally sticks or metal tokens were used to represent the value of skins and goods.

Trading posts were totally unlike the stores of today. There were no aisles to wander down and customers could not pick out what they wanted. Instead, there were shelves displaying merchandise on the wall behind a long counter. The store was open only when traders were present to evaluate the furs.

The stores were unheated to discourage people from hanging about and traders worked in fingerless woolen gloves so they could write up the sales. Trading was conducted as quickly as possible. A heated room was often made available for use by the people coming to trade, with tea and food usually supplied. Inuit customers were welcomed, friendships sprang up, and many traders learned to speak the local language.

In the Bathurst Inlet area, the trapper arrived, mostly by dogsled, staked out his team and built an iglu or put up a tent. He then brought his furs into the store, stacking them on the counter. The trader assessed the furs, establishing a value for each, and laid out tokens to the value of the furs, which were then taken away for storing.

Once all the furs had been evaluated and replaced by a pile of tokens, the customer started selecting the items they desired. Tokens were removed to the value of the item purchased. In the early winter, men came to the post, leaving wives and families behind in the winter camps. But each hunter had been thoroughly briefed by his wife about what was needed.

It must have been like walking into an Apple Store or Canadian Tire today. There were high-tech items of great value—rifles and ammunition, steel knives, hatchets and the like. Matches, candles, and kerosene lamps. Files, saws, and wood planes that could be used to smooth mud placed on the runners of a dogsled. Lamp wicking for dog harnesses that a dog would not eat. Nails and wire, fish nets and hooks, and steel chisels for enlarging a seal breathing hole so the hunter could retrieve the animal more efficiently. There were Primus stoves, metal pots for cooking, metal hooks to suspend a pot over a qulliq (stone lamp). The list went on and on.

Many of the items could make life easier. For example, a steel needle with a hole (through which sinew could be passed) replaced the bone needles women used to sew a set of caribou skin clothing for each family member every year. When using a bone needle, a hole had to be made in the skin, and the sinew passed through the hole, then pulled tight for each stitch. This was tedious work, often done in semidarkness. But the steel needle made the hole itself and pulled the sinew through, increasing the ease and speed with which women could sew. Fabrics were also available to make clothing, bags, and other items of great utility to the family.

For men, the rifle made a huge difference. A muskox horn bow and willow arrows took weeks to make, and though ingenious and powerful, could kill only at close range. This also required the construction of game drives (inuksuit/inukhuit and taluit) that brought the animals within 20 to 30 metres of the hunter. With a rifle, a hunter could take a caribou at 100 metres. But there was also the need for associated supplies and ammunition. In the mid-20th century, this included reloaders, lead for bullets, gunpowder, spoons and molds for casting bullets.

Hunters had no cash to buy these wonders, hence the trading. They were grubstaked, loaned steel leghold traps and taught how to use them. This encouraged hunters to invest their time in trapping. Traders also provided food items—flour, sugar, baking soda, tea, lard, oatmeal—to these men. This food would have been alien to Inuit at that time.

These items were not free. Each involved a debt recorded for that family to be paid off by furs later. The traders spent a lot of time working on the books, recording purchases against furs brought in. The location of the posts was of the upmost importance, to encourage people to return to the post where they had amassed debt, rather than going to a competitor.

Sometimes, life was difficult, especially when there were few foxes, or when sickness broke out in the small camps. Food could be scarce when caribou took another migration route or when the fishing failed. Traders and missionaries helped where they could, sharing food and medical care, but sometimes families could not get to the post, and the journals record deaths in the camps. Many debts were forgiven in difficult times when people were unable to trap. According to the journals, the Bathurst Inlet Post rarely showed a profit. Many Arctic posts did not.

Men usually came in with their first load of furs just before Christmas. They then went back to their traplines, taking their goods home to their families. They would return in the spring, usually around Easter, and often brought their families with them, as the days were longer and travelling easier. This was usually a happy time: families met, socializing with drum dancing, songs, tests of strength, dog races, romancing, and more trading.

Most families only stayed a couple of days, leaving for sealing grounds, areas where they might fish through leads in the ice, or to hunt caribou coming through on their spring migration. Trapping stopped in the spring, as furs were no longer prime. The post staff would concentrate on keeping their books, while also cleaning furs, hanging them to dry in the cold spring sun, and then baling them for shipment. Ships came during the open-water season, bringing trade goods, items for the traders, and picking up the baled fur.

Work on the post buildings was constant. The Bathurst Inlet Post was moved several times between 1925 and 1964. A small Catholic mission church was built in 1934 and 1935, changing the dynamics of the post entirely. One or two priests were stationed there, conducting services when people were around. They helped with health care, and travelled to some of the camps. The Burnside Mission was serviced by the little schooner Our Lady of Lourdes, which came once or twice per summer. Relationships between the priests and the post staff were friendly: they often shared supper, listened to the radio in the evening, and played bridge.

Trade continued through the 1940s and 1950s at Bathurst Inlet Post, just like many small posts throughout the Arctic. But a downturn in the popularity of fur in fashion and clothing meant the profit margins of the trading companies were drastically reduced. Eventually the remote posts closed. People were increasingly moving or being settled into communities, and the time of the proud trapper came to an end, as most families could no longer be supported by trapping. A whole way of life essentially ended.

HBC posts in the larger communities persisted and became general stores, now owned by the North West Company. Through the post journals and books written by a number of traders, many of the stories of the posts have been preserved, providing a window into a remote and difficult life.

It is a glimpse into a time now gone forever.