The North has been coping with the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic for seven months now. While public-health risks appear to be largely contained—assuming we all continue to follow the rules—the pandemic’s impacts continue to roil the economy. Is there a way through this? No one can say for sure. But major economic sectors are identifying the key components of recovery strategies—or at least strategies that will help them survive. Here, we interview leaders from six sectors as they look to the road ahead.

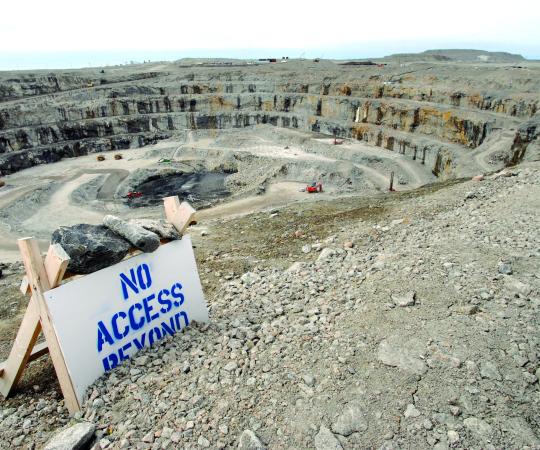

MINING

Stay The Course

Strict health and infection-control measures have spared most northern miners the worst of COVID-19. Maintaining that discipline—as markets show resilience—will keep most in production.

With a bit of imagination, it’s possible to compare some northern mines to cruise ships at sea. Like ships, mines can be strictly defined and isolated places where large numbers of people live and work in close proximity, around the clock. The comparison rings most true for remote projects, where access is strictly fly-in/fly-out, says Tayfun Eldem, chief operating officer at Baffinland Iron Mines Inc., which operates the Mary River iron ore project in Nunavut. So, it’s no surprise the shockwaves that pounded the cruise industry in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic washed over the northern mining industry with equal force.

Fortunately, mining companies had more options available to them, especially related to rapid response. When the magnitude of the crisis became apparent in mid-winter, mining companies immediately put new and stringent restrictions on access to their sites. They sent workers from vulnerable communities back home, with pay, and told those off-rotation to stay put. Strict hygiene and social-distance protocols were implemented, and charter air services were contracted in order to avoid contact between travelling miners and a vulnerable general public. Close communication with public health officials at all levels became the order of the day.

The measures have been an almost-complete success. Only one worker—an Alberta-based employee arriving at the NWT's Diavik diamond mine—has tested positive for coronavirus, and that diagnosis came at the end of July, months after the start of the pandemic. All other mines had reported no cases at press deadlines.

Most have also managed to stay in business, although several report declines in production. The diamond business in the NWT is the exception. The sector has taken an especially hard hit as trading and polishing centres around the world shuttered in the face of COVID-19 lockdowns. The closures played heavily into Dominion Diamond Mines ULC’s decision in March to suspend operations at its majority-owned Ekati project. (They also likely exacerbated the company’s already strained relationship, now playing out in court, with Rio Tinto at the Diavik mine, where Dominion holds a 40 per cent stake.) Mountain Province Diamonds Inc., meanwhile, has reported large declines in mining volumes and diamond recoveries at the Gachco Kué mine, which it owns in partnership with De Beers. To keep the cash flowing, the company inked a US$50-million agreement in June to sell its diamonds to Dunebridge Worldwide Ltd., an investment firm controlled by Irish billionaire Dermot Desmond, a major Mountain Province shareholder.

But the outlook for other sectors, while still challenging, has been more optimistic. After steep tumbles in March and April, world prices for commodities such as iron ore and copper have recovered. Gold has roared back, with prices hovering just below US$2,0000 per ounce at the end of July, a 25 per cent increase since the start of the year. Silver has posted strong gains, as well. Still, broad strength in prices does not translate into immediate benefits for all companies. Baffinland's Eldem, for example, notes that demand from China is currently supporting steel prices. Baffinland, however, exports its ore to Europe, where steelmakers have cutback more than 18-million megatons of steel-making capacity, according to a report by Standard & Poor’s. “I think we’re going to have to wait for things like the return to regular operations of the automotive sector in Europe to regain some confidence in steel,” Eldem says.

Meanwhile, all companies continue to contend with increased costs due to their infection-prevention measures. Eldem notes, for example, that with Nunavummuit workers still at home, Baffinland must import more non-Nunavut-based contractors to work at Mary River. As a result, the company can't schedule as many combi flights of cargo and passengers, leading to increased transportation costs. When Agnico-Eagle posted results for the first half of 2020 at the end of July, it showed a net income of $83.7 million from its operations in Canada, Finland, and Mexico, up from $64.8 million in the first half of 2019. But those numbers were offset by $22.1 million in pandemic-related costs, including $1.4 million paid in standby salaries to Nunavummuit employees.

Pandemic-related operational challenges filter down to the most granular level. “In a pickup truck, a crew cab, we only carry two people,” says John McConnell, CEO of Victoria Gold Corp., which operates the Yukon’s Eagle gold mine. “We have a driver, and the other person sits in the back, in the right-hand seat, to maintain distance.”

Still, strict health and distance protocols have produced a surprising side benefit for northern miners: In addition to keeping sites free of COVID-19, they’ve brought the rate of cold and flus to record lows. “There’s hard evidence this is paying off,” Eldem says. And until there’s a vaccine against COVID-19, adherence to those measures, along with continued consultation with public health offices, remains the best strategy for sustaining a vital northern industry through this crisis. It’s worked so far, and it’s likely to keep working as the world economy finds its path toward recovery.—CL

TOURISM

Keep The Story Alive

Smart marketing will protect the North’s tourism brand. But operators need financial support to reach the other side of COVID-19.

For northern tourism operators, the COVID-19 crisis first showed itself in January, weeks before the monumental threat it posed to health and economies became widely apparent. The portents came as cancellations for aurora tours started to mount, especially from international visitors. By mid-March it was clear how economically devastating the pandemic would be. “I got three groups that cancelled this morning, another group at lunch time. And another a few minutes ago said they may cancel,” Bobby Drygeese, owner of B. Dene Adventures, told Yellowknifer newspaper in a March 16 interview, adding that his customer count had fallen by 70 per cent since February.

Drygeese was far from alone. The pandemic not only hit tourism first, it hit the sector hardest. Cathie Bolstad, CEO of NWT Tourism, estimates the loss during the late-winter, early-spring aurora season at $18 million in direct spending. “That’s pretty huge,” Bolstad says. “And that’s just the direct spend. That’s not the indirect and induced [spending] that comes around.”

The picture only gets darker from there. NWT Tourism projects the sector’s losses at $170 million if the territory’s borders remain closed to visitors to the end of the year. A study by the Yukon Bureau of Statistics published in June puts the drop in tourism activities for 2020 at a minimum of 67.4 per cent, assuming border re-openings for Canadians commenced in July. (The Yukon began easing restrictions on travellers from B.C. on July 1.) Hard numbers are more difficult to come by for Nunavut, where business travel makes up most of the tourism market. But with borders closed and Transport Canada’s ban on Arctic cruise ships, the outlook offers little in the way of optimism. In the first three months of this year, more than a quarter of tourism-related businesses in the territory saw declines of more than 50 per cent, according to data published by Nunatsiaq News.

Complicating matters is the fact that so little is known about the future of the pandemic. Neil Hartling, chair of the Tourism Industry Association of the Yukon, says this uncertainty created confusion for operators heading into the summer. Many struggled with the decision over whether to close for the year—saving money on costs like licence fees and insurance—or forge ahead in hopes of at least a partial recovery. “It’s driving most of them nuts,” Hartling said in a late-May interview. “Some are in a state where they’ve come to the mathematical realization to cut their losses now… Others are just hoping that, somehow, things will work out.”

No doubt it’s been difficult to make decisions for this year, but there is a high-level consensus on what it will take to bring business back. Marketing is the key plank in recovery strategies across the North. All territories have been promoting stay-cations to residents as a means of at least keeping some cash flowing into the tourism sector. And operators have come up with some creative pitches to attract local business. The Town of Hay River, for example, launched the “Hay-Cation” program—replete with retro-postcard branding—to market itself as a getaway for rubber-tire travellers in the North. The Sundog Retreat in Yukon twinned its mini-vacation marketing with an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign to grow food and build a greenhouse to support the Whitehorse Food Bank. By the end of the campaign, it had raised almost $19,000.

But reaching out to local markets is only a drop in the bucket when it comes to mitigating the impacts of COVID-19 on northern tourism. International travel is its bread and butter, and maintaining the North’s brand in a globally competitive market will require sustained and thoughtful efforts. Early indicators suggest the territories are heading into that task on strong footing, Hartling says, noting that many people who booked with Yukon tour operators this year left their deposits with companies—a clear indication of their intent to take the vacations they booked. Bolstad also says the NWT has built a good brand and strong partnerships in important international markets that will support its work going forward. The emphasis now is crafting marketing messages that work with the reality of border closures and travel restrictions. Instead of encouraging potential travellers to book trips now, Bolstad says, NWT Tourism is portraying the territory as a destination to visit when the time is right. “Until the borders open, the focus will be on how to keep dreams alive,” she says. “We need to create the sense ‘Oh my god, I want to go there. It’s worth the wait.’”

Still, the question remains: How long can the industry hold out? After all, you can’t sell last night’s empty hotel room like day-old bread or offer curbside pickup for a paddling tour. Before the pandemic recedes and interest in tourism starts returning to more normal levels, the North’s sector will need financial support. That will help ensure it survives in sufficient shape to deliver the quality of products it’s known for, Hartling says. Ottawa recognized this recently when it extended the Northern Business Relief Fund by eight months to March 31, 2021. The program offers grants of up to $100,000 to qualifying businesses and the extension is primarily intended to support the tourism sector. It will need it. But if efforts to control COVID-19 through the coming winter months succeed, it may be just enough to get tourism on the road to recovery.—CL

ARTS AND CRAFTS

Go Virtual

Northern artist have turned to the internet and social media to keep their work in the public eye. Governments have helped. But recovery will require the end of travel restrictions.

For business owners, everything has been up in the air during the COVID-19 pandemic. But the big problem for northern artists is that nothing is up in the air. Airplanes, specifically. In the wake of border closures, Condor flights from Frankfurt to Whitehorse, an important conduit for international tourists to the Yukon, were cancelled. Nunavut enacted the strictest travel restrictions in the country. The NWT also blocked leisure travel, and essential travellers allowed to enter at all required an approved isolation plan.

With the border lockdowns came the loss of an important customer base for fine artists and craftspeople across the territories. Musicians and other performers suffered, too, as festivals—large and small—disappeared from the northern calendar. “I think when this all started, artists were definitely, across the country, one of the hardest sectors hit coming into the summer season with all the cancellations of events,” says Johanna Tiemessen, manager of arts and fine crafts with the Northwest Territories Arts Program.

That observation has resonated with governments and arts leaders across the North, and efforts to support the sector have been ongoing. In mid-May, the NWT government announced $250,000 in funding to help artists impacted by the cancellation of events and festivals. The Yukon government doubled the budget for its Advanced Artist Award, which focuses on established creators, to $150,000. The funding was distributed to 22 artists to develop new work. [Disclosure: Amy Kenney, the author of this piece, received funding under the program.] In Nunavut, the territorial government recently launched a public art initiative that will provide grants of up to $50,000 to selected artists to create and install new works.

But what about audiences? To maintain the connection, all three territories have moved online in the form of live-streamed shows, remote courses, and teaching elders to use social media to promote their work. For example, Will Huffman, marketing manager with Dorset Fine Arts—the Toronto representative of the world-famous West Baffin Eskimo Co-op—says he’s facilitating virtual studio visits, shows and artist talks, including one by Qavavau Manumie, who currently has work in a show at the Museum of Modern Art in Poland. But Huffman wonders if that’s a feasible long-term strategy. As always in the North, there’s the issue of bandwidth and internet reliability. There’s also what Huffman calls the nature of the art world—contingent on buyers having a cocktail and chatting with the artist while looking at the work.

On top of that, Dorset doesn’t currently have the inventory it usually does. Nunavut’s Kinngait Studios—the West Baffin co-op’s centre for sculpture and printmaking—closed for a period this spring. Even since reopening with restrictions, fewer artists have used the space. Many have children or grandchildren and rely on the school year to give them time for work. When school ended three months early in Nunavut, it represented the loss of a huge chunk of production time. In a typical month, Dorset spends $60,000 on carvings and $35,000 on drawings. Compare that with June 2020, when it spent $25,000 on carvings and $20,000 on drawings. The shortage of inventory, Huffman says, makes him wonder about pursuing the European market (it’s opening faster than North America) more aggressively as part of Nunavut’s recovery plan.

In the Yukon, meanwhile, Tourism and Culture Minister Jeanie Dendys says the Yukon Tourism Advisory Board and the Business Advisory Council have both been working to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on the arts sector. Examples include the “Not Close But Personal” concert series, a Facebook live event, funded by the territorial government, where artists stream performances from their homes or the Yukon Arts Centre.

Meanwhile, Arts in the Park, an outdoor concert series in Whitehorse hosted by the non-profit, Music Yukon, partnered with CJUC to broadcast performances instead of hosting weekly public events. Policy adaptations have also been made to the Yukon government’s Touring Artists Fund, which helps artists and performers travel outside the territory, to enable online and in-territory performances.

But the question remains: How long can virtual connections stand in for the real thing, and how will the relationship with audiences evolve? While it’s important to look at recovery plans, Huffman says, it’s equally important to consider what it might mean not to recover—to develop new models and ways of doing things. “When (re-opening) does happen,” he says, “if you build it, will they come?” If the brand strength displayed by the tourism sector holds up, its close cousins in the arts field have reason for cautious optimism for recovery. But no one knows when.—AK

TRANSPORTATION: PART 1—Aviation

In Thin Air

Northern airlines are weathering steep declines in traffic with help from government. They’ll continue to need support until a broader economic recovery takes hold.

When Joe Sparling looks down the aisle of one of Air North’s Boeing 737s, he doesn’t see most of its 120 comfortable seats filled with paying passengers. In April, he might have seen only 15. Fifteen. “This is the worst challenge that I ever have seen, and the worst challenge commercial aviation has ever faced,” the airline’s founder and president told CBC in an early May interview. “With our year-over-year traffic down by 96 per cent in April, we have had to reduce capacity drastically, while still maintaining a minimum level of essential service to the communities we serve.”

Airlines across the North echo Sparling’s blunt assessment. None argue the need for the tough measures imposed to contain COVID-19. But it leaves them all desperate for some signal of certainty that—sooner rather than later—they’ll still have viable businesses to support the North’s critical reliance on airplanes.

The woeful numbers at Yellowknife’s YZF airport help tell the story: passenger movements in April were down 92 per cent from 2019—35,603 to 2,724—and aircraft movements were almost halved, from 4,470 to 2,389. Canadian North, the brand that carries its recently merged routes with First Air, still flies to 25 hub communities across the NWT and Nunavut and into Montreal, Ottawa and Edmonton. But Andrew Pope, a vice-president at Canadian North, says the airline carried only 10 per cent of normal passenger loads in May, mainly medical and essential worker traffic. (Freight is slightly above average as shipments of groceries and medical supplies have grown.)

Meanwhile, Chris Reynolds, president and CEO of Yellowknife-based Air Tindi, has parked half his fleet of 19 aircraft and let go 50 people from his 120-strong team. “We’re just over half of our size,” Reynolds says. “We can make it work, but it’s not pretty. It’s still a crisis.” Anchored by essential medivac services and scheduled flights to four regional communities—down from five—Tindi, like many small to mid-size carriers, needs the return of charter traffic from tourists, miners, and remote construction crews to get healthy. And until national and international borders begin to open up, that means just one thing to them all: serious cash to support them through the crisis.

To that end, the federal and territorial governments have been providing relief to aviation firms in the form of waived fees for leases and licences, and in direct financial support. Drawing on Ottawa’s $130-million aid package to northern business, announced in April and flowed through respective territorial governments, the NWT has paid out $13.6 million to five aviation companies providing essential community links, and to 10 other smaller charter firms. Yukon has paid out $3.6 million to its aviators. In Nunavut, federal and territorial support to airlines stands at close to $24 million, including $9.6 million paid to Canadian North and Calm Air between March 30 and April 30 that the territorial government would have spent on medical and duty travel under normal circumstances.

“If the demand doesn’t come back, we expect a long slow grind in terms of a recovery. We expect that need for [government] assistance will be there for some time to come,” Canadian North’s Pope says. “It’s going to be about building up confidence in people about travelling again….That’s going to be a challenge for industry. It’s very likely that frequencies will be lower than they were. As far as price… it remains to be seen.”

The balancing act between lower revenue, extended financial aid, and fixed operating costs complicate the industry’s future. Looking ahead, Air Tindi’s Reynolds argues for policies and programs that will nudge tourists and miners to book his planes again. “For us to be back at any close range of normalcy, it definitely requires stimulus to the [larger] economy,” he says.—BB

TRANSPORTATION: PART 2—Ground and Marine

Keep ’Em Rolling

Despite lockdowns and travel restrictions, essential truck and marine traffic is holding steady.

While most regular folks feel pinched in their personal travel desires, the movement of essential goods and supplies by road and waterways continues almost unhindered in the North. In large part, that’s because their cargoes—and the people who move them—were declared essential by all governments in the first days of the pandemic, says Larry Wheaton, vice-president of operations for RTL Robinson Enterprises of Yellowknife. “It’s continued across almost all sectors pretty much without consequence,” Wheaton continues. He also notes that long-haul drivers were the most affected, as the roadside restaurants and rest-stops they relied on shut them out in COVID-19’s early stages. That hindrance has largely been smoothed out. “They persevered,” Wheaton says. “Nothing slowed them down.”

When the threat of the pandemic became clear in early 2020, the Yukon and NWT both moved to block or control entry. All told, the territories have nine access points through Alberta, British Columbia, and Alaska. And while any Canadian has a Charter right to cross any border, each province and territory can set conditions under which people may stay, including demands for self-isolation if travellers are not on their way to somewhere else.

Meantime, ground transports are down substantially. Vehicle movement from Alberta to the NWT thinned by about 20 per cent per day in April, according to the NWT Department of Infrastructure. For the seven weeks ending May 21, only 2,200 border crossings were logged with almost 1,500 of them by transport trucks. The Deh Cho Bridge slipped to 304 crossings per day from a typical load of 375. Along the Dempster Highway, traffic actually increased in April (from a daily average of 30 to 42) perhaps due to trucks anxious to beat the river breakup.

Vital marine shipping down the Mackenzie River and into the Western Arctic’s 12 communities proceeds as usual, according to the NWT Department of Infrastructure’s Greg Hanna. “We do not anticipate any major impacts on Marine Transportation Services due to COVID-19 at this time,” he said in an email (although high water levels delayed some early departures). Sealift companies serving Nunavut, meanwhile, are taking strict health precautions and expect a relatively normal shipping season, although volumes may be smaller due to delays at some construction projects.—BB

CONSTRUCTION

Shop local

Construction companies elsewhere in Canada are looking north for business. Northern contractors say governments need to focus on supporting local firms.

We’ve heard it so often—Buy North. Today, in the face of COVID-19, the cry is orders-of-magnitude more critical for resident contractors, builders and engineers. They’re dealing with a double-barrelled threat: New project opportunities are dramatically curtailed. And when they do come up, southern firms anxious to fill their own scant order books are trawling territorial tender calls for work. In the face of that competition, northern industry leaders are looking to federal, territorial and municipal governments for support.

“Our governments need to recognize that spending close to home is the wisest decision,” says Kevin Hodgins, who leads a team of 70 professionals in all three territories for the international engineering and environmental firm, Stantec. “They’ve got to make bold and forthright and forward-thinking decisions, recognizing that they’ve got to support those that are invested and local.”

Jack Rowe, president of the family-run Hay River-based contracting company, Rowe’s Construction, echoed that sentiment in a June interview with CBC, saying that NWT has to find new ways to support local firms—otherwise his company might have to leave. “We were born and raised here so we really don’t want to go,” Rowe said. “[But] if there’s not going to be work afforded to you … then you have to find other markets or get out of the business.”

Now the focus of construction industry concerns, Buy North policies are strongest in Nunavut, where all qualified Inuit-owned, Nunavut-based, or local businesses are granted a competitive adjustment of between seven and 21 per cent based on a range of criteria. But that advantage erodes as you move west. The Yukon government’s buying policy offers few tangible advantages. In the NWT, the Business Incentive Policy (BIP), gives Northerners a 15 per cent advantage on contracts up to $1 million, plus a five per cent adjust for firms in remote communities. However, not much gets built for a million dollars, and the NWT advantage fades rapidly above that threshold. It falls to just 1.5 per cent for NWT firms and 0.5 per cent for local adjustments after a contract’s first $1million.

While concerns over taxpayer value and international bidding treaties drive those percentages, Hodgins fears they may be self-defeating as construction firms in the territory struggle through the pandemic fallout. “We’re seeing more competition that doesn’t live here,” he says, adding that where he used to see maybe three bids for a tender call, there are now up to 10. “Some [competitors] are foolishly hungry, undercutting the norms of purchasing close to home. Our government clients need to really scrutinize the Business Incentive Policy and… actually, to go beyond the BIP.”

Beyond major contracts, new home construction and renovation is one tool northern governments have applied to keep contractors active this year. In the NWT, for example, the government has announced that more than 100 units, identified during the coronavirus pandemic for the territory’s homeless, will be renovated this year. The NWT also has about $43 million in its capital plan for new housing construction and retrofits. Local firms will pick up the vast majority of that work, which is standard practice.

In Nunavut, the most immediate impact of the COVID-19 crisis has been how to enable hundreds of seasonal, southern workers to get to job sites and stay within protection guidelines. “This includes over 50 capital projects valued at approximately $600 million,” Community and Government Services Minister Lorne Kusugak said in a May 28 update. With the short summer and fall window for Arctic construction, Nunavut had little choice but to ensure each worker from outside the territory self-isolated for two weeks before heading north. Some part of their wages may also be funded by the government.

Yukon’s builders suffer from a further complication caused by the pandemic, says Terry Sherman, executive director of the Yukon Contractors Association. Safety protocols for incoming workers are out of sync between regions, communities, and government rules, he says, which leads to confusion and suspension for some projects. “We just wish everybody would get on the same page.”—BB