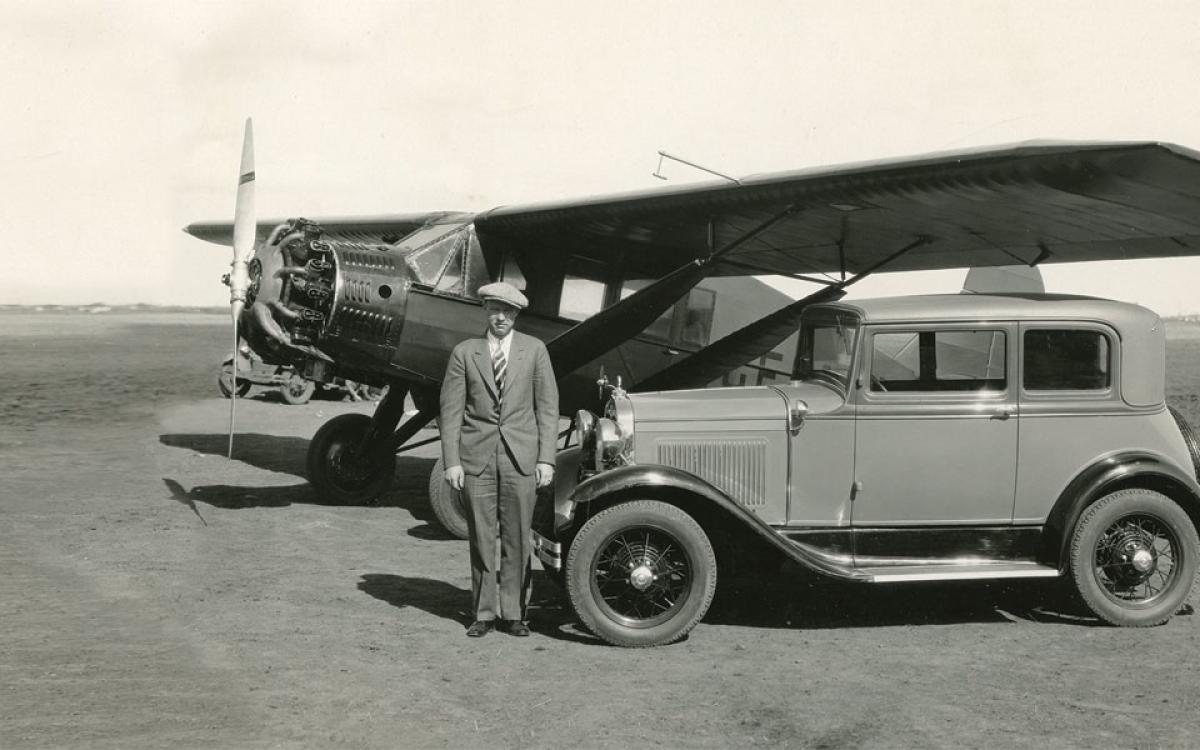

It’s December 1930. World War I ace and pioneering bush pilot Wop May lets out a deep breath and taps his lucky carved wooden monkey, hanging in the cockpit. He steps out of his Bellanca CH 300 Pacemaker into a frigid Aklavik afternoon. With that, the North’s aviation age is heralded in with the first contract mail run beyond the Arctic Circle.

Before the end of 2017, North-Wright Airways founder Warren Wright could get a sense of how that felt by replicating the route in the very same make of aircraft—minus the wooden monkey. He’d also like to re-enact May’s famed 1932 search for the Mad Trapper, conducted with a Bellanca, by landing on the Rat River. “I’ve got the skis for it too,” he says. “A set of original skis.”

Wright has a lot of time to consider the many historic flights he might make, as he patiently waits for his refurbished antique 1929 Pacemaker to be fitted with floats in Oregon before he can fly it home to Norman Wells, NWT. He did get to spend a tantalizing hour in his long-distance aircraft at an American airshow last summer—the first time he’d left the North during that busiest of seasons in 40 years. “It’s rock-solid in the air,” he says of the Pacemaker. “It just doesn’t go up or down until you tell it to. It just sits there like a rock.” But to manoeuver it, you need to manhandle it. “It reminded me of taking a DC-3 around in a turn,” he says.

This isn’t Wright’s first vintage plane—a 1941 Gullwing Stinson fell into disrepair after his business first took off 30 years ago—but he’s excited about bringing up the Bellanca, considering its legacy in the North, and the Mackenzie Valley in particular.

Wright knew about Wop May’s exploits, but the more he looked into Bellancas, the more history he turned up. Charles Lindbergh, for instance, wanted to use one for his solo transatlantic flight, but opted for a Ryan after a disagreement with designer Giuseppe Bellanca. A Bellanca also held the record for the longest continuous flight for decades. “If you look up the American history of the Bellanca Pacemakers and Skyrockets, they just continually broke records, one after the other,” says Wright. “But in Canada, it was a bush plane.”

Some of the North’s most enduring mysteries and notable flights involved Bellancas: Johnny Bourassa had been flying one when he went missing in 1951, never to be seen again; a 30-year-old Max Ward flew into a hill near Bathurst Inlet, barely avoiding disaster, in a Bellanca Skyrocket.

Eventually, newer bush airplanes took the place of the Bellancas. These included the Noorduyn Norseman (designed by Robert Noorduyn, who cut his teeth under Giuseppe Bellanca’s tutelage) and de Havilland’s Beaver and Otter, with their short take-off and landing capabilities.

There aren’t a lot of Pacemakers around these days. “It was a wood-wing airplane,” says Wright—many were wrecked, others fell victim to hangar fires. Wright hopes to have his red Bellanca buzzing over the Sahtu early this summer, once the onerous paperwork process to register it in Canada is complete.

But he won’t put his Bellanca to work like the Pacemakers of yore. Wright will take it out for fishing trips and joyrides with friends. And that entire experience could be 1920s-specific—including the drive to the Norman Wells airport. “I got a 1926 Model-T sitting here,” he says, chuckling. “I was into antique cars before I was into airplanes.”