Uqariurumajunga - I want to learn to speak the language

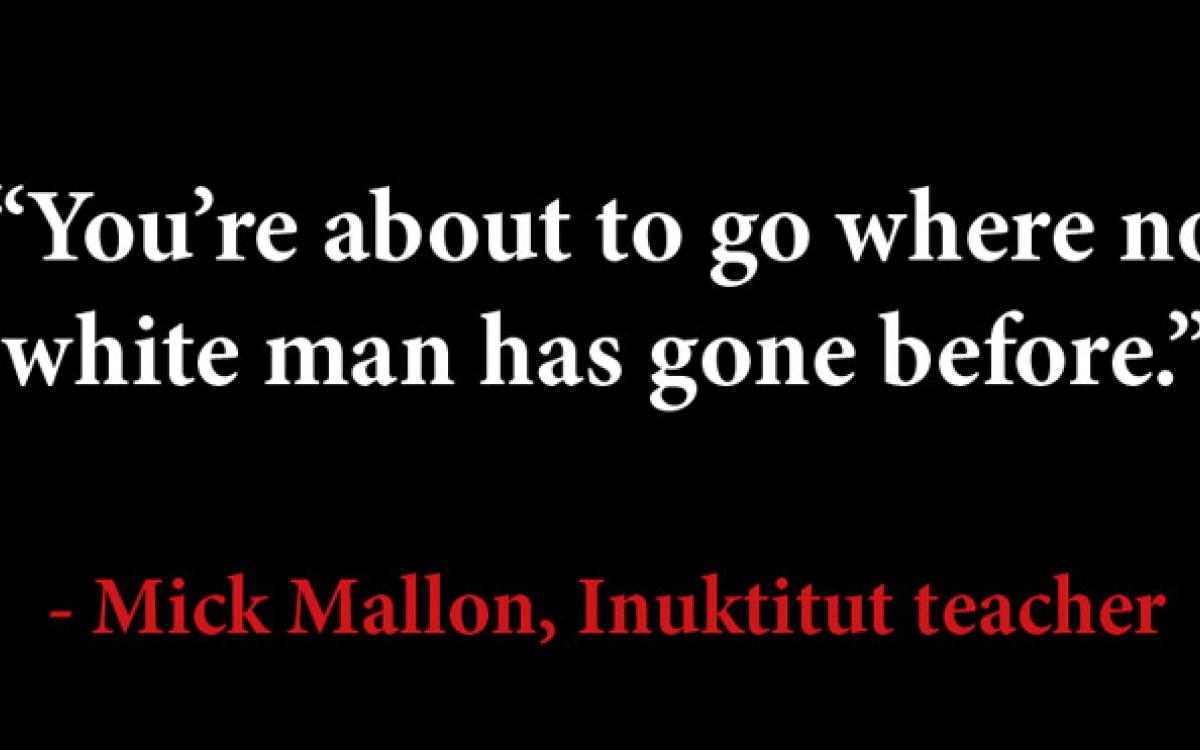

You’re about to go where no white man has gone before,” Mick tells me, and I take a deep breath, then try to pronounce qimmiq. The q sound in Inuktitut is not the Q in Queen. It comes from deeper in the throat and rumbles out as something between a k and an exhale.

I spent a year learning the very basics of Inuktitut, two lessons per week, with my colleague. Our teacher, Mick Mallon—an Irishman who spent his adult life studying, learning and then teaching Inuktitut across the North—would watch sympathetically, and often laugh out loud on the other end of a Skype video call, as we attempted to summon strange new sounds and break the habits of our mother tongues.

Inuktitut carries with it a very specific logic and approach that is drastically different than that of the Germanic and Romance languages I grew up with.

The Inuit’s relationship to sounds, for instance, was challenging to me. “Never trust a t,” Mick told us. “Or an s.” In Inuktitut, the two sounds are often interchangeable. That was hard for me to grasp intellectually, but once I did it seemed intuitive biologically. Both sounds are alveolar—produced with the tip of the tongue’s placement on or near the roof of the mouth, just a centimetre’s movement in between.

Ideas are expressed not as a string of words fitted together, however rambling and haphazard as they can be in English, but as a string of noun chunks and verb chunks, and noun endings and verb endings, which get extremely specific. Sometimes the English sentence seems simpler, but a skilled Inuktitut speaker can be much more efficient. Say you’re on a rooftop looking at traffic, trying to figure out which car your friend is in.

Uumanngat—inside this one here.

Iksumanngat, inside that one over there.

Matumanngat, inside this one here that is moving.

Aksumanngat, inside that one over there that is moving.

Ipsumani, Inside one that we cannot see.

Taipsumani means inside one that we can’t see, but that we’ve established is there. It can also mean history. Then there are variations of the one up there (and up there, but moving), down there, etcetera.

We’d turn off Skype after an hour-long lesson and sometimes I’d just stare off into the distance, digesting what I’d just been told in the language of the Arctic.

After a year of getting progressively deeper into the language, with occasional breakthroughs and many headspinning crises, work picked up and I could no longer find time twice a week to learn.

I miss it. It’s not just that learning Inuktitut is a massive workout for the brain. And it’s not just about exploring a language that is beautiful in its tones and rhythms, and in its marvelously logical structure, or about how to express ideas, facts, and emotions, or how to piece together meaning. It’s about learning how the Arctic world was articulated by the people who lived here for generations before my parents arrived.

Note: Sorry if I got any of my words wrong, Mick. Qablunaangujunga. Ajurnarmat.