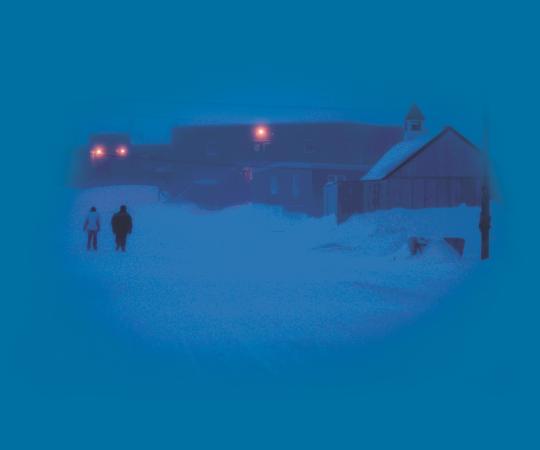

It’s just after 9 p.m. on a chilly Sunday night in early December, and there are four buses idling outside Yellowknife’s Explorer Hotel, one of the largest—and arguably most luxurious—hotels North of 60. As the exhaust from the buses swirls in the cold air, dozens of people wearing identical blue parkas wait inside the brightly lit lobby. Before long, guides call out instructions—in Korean, Japanese, Chinese, and English—as the group board the buses, bound for Aurora Village, the largest aurora-viewing operation in the NWT’s fastest growing tourism sector.

The Northern Lights have become big business in Yellowknife in recent years, and the scene at the Explorer tonight hints at the scale of investment in the industry. Consider: The buses outside the hotel are just a fraction of the 20-odd owned by a dedicated subsidiary of Aurora Village. The parkas the visitors are wearing, which fill a cavernous room beneath the company’s downtown office, represent a $600,000 investment in winter clothing alone. But the “village” itself is the true jewel of the business, and stepping off the buses half an hour later, it becomes clear why.

Across a frozen lake, a row of eight tipis is illuminated from within, giving them a soft glow beneath the big sky the visitors are here to see. Perched above the lake is a log cabin-style restaurant where dishes like bison gyoza, bannock-fried fish tacos, macaroni with Arctic char and local beer are served until the wee hours of the morning. Dogs howl nearby, waiting for their chance to pull a dogsled around the lake. On some nights guides do an “ice show” complete with the Instagram-friendly hot-tea-freezing-in-midair trick. All these accoutrements are meant to keep the visitors—who have paid $126 just for basic entrance—entertained and busy while they wait for the real show to start.

The scene here tonight plays out again and again from mid-August to October and again through the winter. And the numbers add up. In fiscal 2017-18, aurora viewing attracted 34,900 visitors, according to NWT government statistics, accounting for just under half of the total leisure visits to the entire territory. Aside from fishing and hunting, it’s the only game in town in terms of luring international tourists. Luckily, the game is strong: Those tourists left behind nearly $57 million last year, a 171 per cent increase from five years before.

To accommodate the growth, the Explorer Hotel has added 72 new rooms in a massive renovation, bringing its total to 259, while the Chateau Nova has opened right next door with 141 rooms of its own. Airbnb has also taken off in the city, nearly tripling from 70 to 190 properties in just two years.

Meanwhile, more than 60 licensed companies in the Yellowknife region now offer aurora tours of one kind or another. Unlicensed tour operators have proliferated as well. Everyone wants a piece of the ever-growing pie.

But none of this preparation matters if the anxious throng of tourists staring longingly at a cloudy, dark sky on this night don’t leave happy. “It’s probably some of the worst weather I’ve seen since I’ve been here,” Aurora Village CEO Mike Morin, son of the company’s founder, Don Morin, had complained in his office earlier in the week. The weather had socked in for most of November, blocking the multi-million-dollar view.

With only a few days on the visitors’ schedules and only a few hours at Aurora Village, the clock is ticking for nature to draw back the curtain that has settled over Yellowknife since the start of the winter season. The payoff for the restless tourists comes a little more than two hours later when, just after midnight, the aurora come out from behind the clouds. The crowd cheers, rushing from their tipis and the lodge to make the most of an unforgettable experience—a story they’ll share with friends and family for years to come. Northerners across the three territories can appreciate the sentiment, even though the lights are a common sight. But for those hoping to develop business opportunities themselves, the real story is how Yellowknife became a global aurora-viewing capital in the first place.

If Yellowknife has one advantage as an aurora destination, it’s geography. The city sits under one of the most active regions of the aurora oval, a circumpolar band where the Northern Lights appear. That fact is reinforced by aurora “lighthouses” scattered throughout the city that glow different colours depending on the current strength of solar activity that drives aurora displays: green means “calm,” while red means there’s a solar storm raging above.

Unlike true lighthouses, demarcating a coastline that has always been and will always be there, there was nothing inevitable about the aurora business in Yellowknife. In fact, what has become an industry has humble origins. The story begins in the late 1980s, when a Japanese executive with the now long-defunct Canadian Airlines named Toshi Togo visited Yellowknife, saw the Northern Lights and reckoned that Japanese tourists might be interested in coming to the city to see the show.

Togo approached local businessman Bill Tait, whose company Raven Tours had been running more conventional tours at the time. Tait was intrigued and he brought the idea to local world champion dog musher Grant Beck, who was already running dogsled-based aurora tours for a smattering of mostly European clients. Tait and Beck started making regular trips to Japan, developing relationships with travel agents and gathering information on what Japanese customers wanted from their Northern experience. In 1989, Tait and Beck brought the first Japanese tourists to Yellowknife. There were 80 people in that pioneering group. “We had tents on Vee Lake, and we would go out there,” Tait recalls, referring to a popular recreation spot just north of Yellowknife. “We had a little wood stove.”

Raven Tours grew gradually through the 1990s, with Tait and Beck making regular trips to Japan to gain insights into the market they hoped to win. They tailored their trips to group travel; they started hiring Japanese staff; they added and removed activities like dogsledding, ice fishing, and even a plane trip out to a lake to see caribou. To market their business, they invited Japanese celebrities such as sumo wrestlers and musicians to experience Yellowknife and the aurora, as well as Japan TV crews. At one point in the 1990s, their efforts were buoyed by a national commercial for Nippon Ham in Japan, which proclaimed itself to be “as pure as the aurora borealis” while featuring a celebrity under the Northern Lights at the Raven Tours camp.

The effort paid off. By the turn of the millennium, Raven Tours was bringing in 12,000 guests annually. Northern News Services printed a story with a sub-headline that reads like a harbinger in retrospect: “Tour company predicts continued growth.” Then came Sept. 11, 2001. Tourism crumbled worldwide. “People just stopped traveling,” Tait says. Aurora tourists were no exception.

Raven Tours’ business fell by 75 per cent in the aftermath of the devastating terror attacks that toppled the World Trade Centre in New York City. Only 3,200 people made the trip to Yellowknife that year, and Tait found himself scrambling to stay afloat. He laid off staff and reduced Raven Tours’ vehicle fleet, all while struggling to keep paying for a new aurora-viewing facility he was building at Prelude Lake, home to a territorial park and recreational cabins about a 40-minute drive from Yellowknife.

By the time the Japanese market recovered two years later, Raven Tours was essentially gone. Tait was out of the business, while Beck carried on to rebuild. The following year saw the SARS outbreak, a second blow to tourism worldwide.

Just as Beck was struggling to recover from the twin blows of 9/11 and SARS, a new player was staking a claim on the Yellowknife aurora tourism scene: Aurora Village. Founded in 2001 by Don Morin, a former NWT premier originally from Fort Resolution, it is now one of the biggest aurora tour operators in the world, with 20,000 people coming through its gates every year. But when it launched it didn’t even have its eponymous village. That accident of timing may have saved it from the same fate as Raven Tours.

The first year, with a location barely established and just a single tipi on the lake, Aurora Village brought in 450 customers, a sign of the success Tait and Beck had had in developing the industry. It grew quickly from there, aided at times by local companies like Weaver & Devore, a historic local outfitter that sold Morin parkas on credit, and Kingland Ford, which did the same with vehicles. “You start small and you just keep adding,” says Don Morin. “It got to, like, 1,500, and then I think there was a big jump to 3,000, and it just kept growing and growing.”

Morin had a few key strategies that worked in his favour. The first, something any Northern parent knows, was to keep the customers warm. “If you want your kids to play outside, dress them warm. Do the same thing for the customer,” he says. “If you dress them very warm, that’s half the battle.”

That same strategy extended to equipment. Adapting a trick Morin’s father had used to stay warm hauling logs across Great Slave Lake, the company built astoundingly comfortable heated outdoor seating at its viewing site. Morin says learning from the fate of Tait’s Raven Tours, Aurora Village was careful not to overextend itself. He built cautiously, growing in capacity when there was cash on hand to fund it.

Like Tait, the company focused on group tours, partnering with hotels to make sure their customers were taken care of from the moment they came off the plane until the moment they left. But the success of the firm cannot account for the explosion of aurora tourism that was to come. Back in those days, the word “tourist” had become synonymous with “Japanese” in Yellowknife. But a new market beckoned: China. It was rich with potential thanks to a growing middle class eager to travel. But it was also one that would be tough to crack.

In the mid-2000s, as he was building a new business, Aurora World Tours, Beck began travelling to China to promote aurora tourism. “I don’t think anybody knew it was the right time, we just started going,” he says. “We just travelled everywhere.” Beck faced a major hurdle, though: Chinese citizens at the time were allowed to travel to only a handful of countries without going through a lengthy and expensive permitting process. Moreover, travel agents couldn’t advertise or organize group trips to Canada. Beck says Tait, by then out of the aurora business, advised him that his efforts were probably futile. “He didn’t think China was going to jump on board like the Japanese did,” Beck recalls.

Then in 2009, just ahead of the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, Stephen Harper returned from a trip to China with a major prize: “Approved Destination Status,” a designation from the Chinese government that made it easy for Chinese travellers to visit Canada and permitted Chinese travel agents to promote Canada as a destination and organize group travel.

Verda Law saw the opportunity and started her own company, Yellowknife Tours, in 2010, which specifically targeted Chinese guests—the first of its kind. It was a struggle, however, to convince Chinese customers that Canada could even be a destination for that kind of tourism. “People didn’t think that Canada can see aurora,” she says. “They thought we were from Finland, Norway, Northern Europe.” Law began putting a Canadian flag on her booth at Chinese trade shows.

The influx of new tourists started as a trickle: that year, in a near replay of the early days of Japanese tourism, only 84 of the 66,000 people who landed at the Yellowknife airport were from China, according to territorial government data. The businesses were persistent, however, with support from the government as then-premier Joe Handley joined in on a trip to a trade show.

And the trickle of Chinese visitors began to grow, supported by more trips by NWT government leaders to promote tourism to major travel industry associations in China. Meanwhile, partnerships between NWT Tourism, the territorial marketing agency, and Destination Canada, the national tourism marketing agency, helped build business-to-business relationships between NWT tour operators and travel agencies in China and other markets, notably Korea, supported by ongoing marketing campaigns in both traditional and new media by NWT Tourism. On the ground in Yellowknife, growth in the number of companies offering aurora-related tour packages ensured the product would be available to anyone who came.

The results of these efforts speak for themselves. In the 2017-18 fiscal year, the number of Chinese visitors coming to Yellowknife hit 6,200—a total that came within spitting distance of the number of arrivals from Japan for the first time. A new company has even started using the name Raven Tours, with Tait’s blessing. Its guides speak Chinese.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, as the old saying goes. And in Yellowknife’s case, it shows how competitive aurora tourism has become. If you type “auroravillage.ca” in your web browser, for example, you don’t land on the Aurora Village website. You’re directed instead to the website of Northern Lights Tours, a small company run by Julian Botnick. “When I first started my business, everyone was coming off the plane asking to go to Aurora Village,” he explains, adding that his guests—many of whom speak limited English—were assuming the company’s location was itself the only place where the aurora would be visible. “They had it in their minds that that’s where you had to go to see aurora.”

Botnick is an aurora chaser, which means his tours are mobile, searching for the aurora each night along the Ingraham Trail, a rough-hewn 70-kilometre highway leading out of Yellowknife through cabin country. Botnick is a licensed operator, but there are also unlicensed guides—operating outside NWT regulations—crowding the roadside pullouts. Botnick says he’s seen some dangerous situations on his tours. “I’ve seen everything. People stopped in the middle of the road on the Ingraham Trail in the middle of the night. People pulling U-turns all over the place. It’s so dangerous,” he says.

There was one incident recorded in 2018, when a vehicle belonging to new operator hit another tourist in a parking lot near the now-closed Giant Mine, a short drive from Yellowknife’s city centre. There were no serious injuries in that case, and no criminal charges. But Don Morin thinks it’s just a matter of time before something worse happens. “When somebody does get hurt, we’re all gonna pay because we’re all painted with the same brush. In the end, you know, when somebody gets killed, then it’s Yellowknife tourism [that suffers].”

And crowding by unlicensed operators is only one challenge legitimate tour operators face as their industry grows. Workers who can speak Japanese, Chinese or Korean are at a premium, and visas are hard to come by. Both Aurora Village and Northern Lights Tours rely on working holiday visas, as is the norm in the industry, meaning their employees usually only stay a single season. Aurora Village invests heavily each fall and winter season training their staff. “We’re bringing in quite a bit of new staff every year,” says Mike Morin. “And new—not just to the North, but to Canada and the cold. So we do six weeks of training every year with our guides.”

Changing weather patterns are also a concern. Over the 50 years spanning 1952 to 2002, cloud cover increased in Yellowknife by about 10 per cent—862 hours. That’s over a month’s worth of cloud cover, and it hasn’t gone unnoticed. In a recent marketing plan, NWT Tourism noted “changing weather patterns” as a potential challenge to the industry. Beck rejects the concerns, saying his numbers show that no matter what the weather his clients still get to see aurora “95 per cent” of the time over a three-day trip. Still, perceptions matter, especially when you consider the cost of travel to the North. If clients come to believe that cloud cover will reduce their chances of seeing the aurora after travelling so far—and at great expense—they may decide to spend their money elsewhere.

But at least these are challenges that are well understood. And as another saying goes, what can be measured can be managed. Yellowknife’s aurora industry has already proved adept at building an international business from scratch. The throngs of people in blue parkas walking the streets, filling the restaurants and boarding buses at night during the peak season are proof of that. Sustaining the momentum depends on the ability of the aurora industry to understand its market, grow new opportunities, maintain the quality of its product and—above all—work with the realities of the Northern night sky to make sure visitors see what they came to see.