It’s an unpleasant cognitive dissonance when you know you should be thankful—but you aren’t.

Modern air travel is a miracle and the result of many people’s diligent industry. I ought to be astonished arriving in the High Arctic in anything under thirty days, with dry feet even. But my appreciation is lacking today. Despite the captain’s even-keel tone as he announces the course change miles above the tundra, I am less than enthused about returning to Yellowknife due to mechanical issues.

Hours later, we make a second unblessed attempt to depart for Taloyoak—Canada’s most northerly community on the mainland. Eventually, a reserve plane is wheeled out. My morning flight home has become an evening trip—‘milk run’ stops still included. The Grumpersons are moving in.

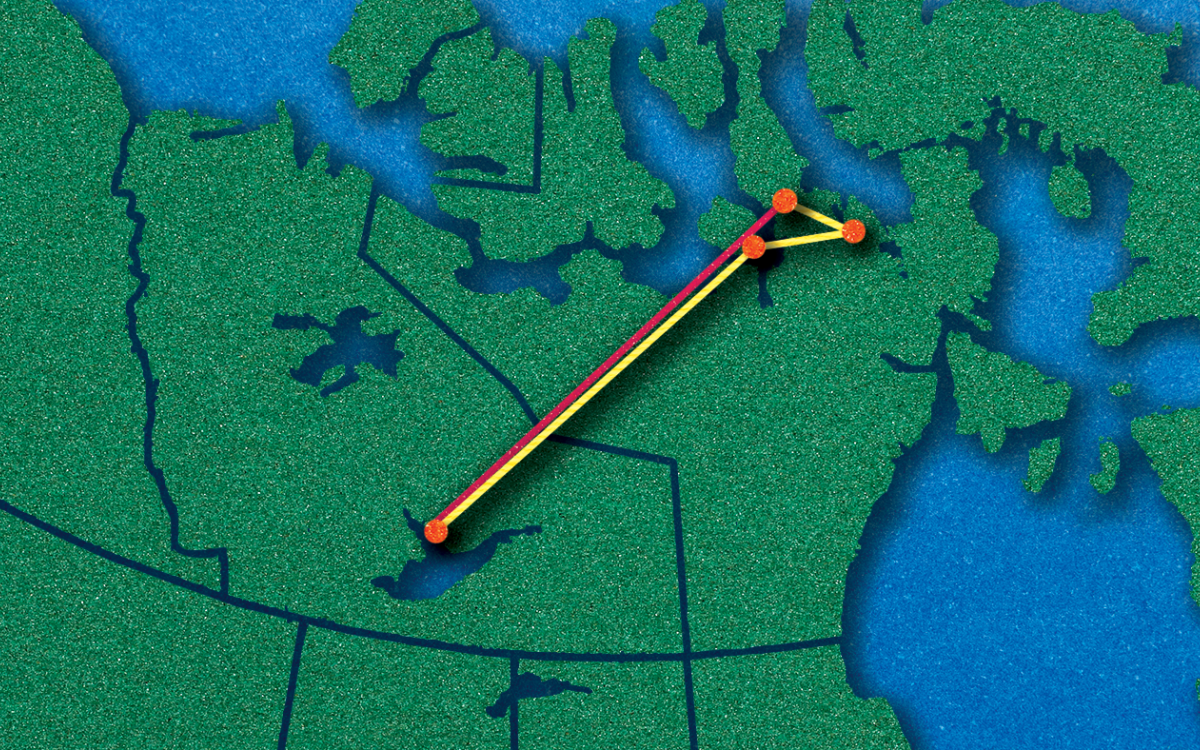

We lift off and my worry is now that something else will go wrong. We land in Gjoa Haven. No issues. We touch down in Kugaaruk, the neighboring community. No issues. Twenty more minutes and I’m home. But the flight attendant addresses those passengers heading to Taloyoak: they’re skipping our stop. The pilots have been up too long—“Transport Canada regulations.” We’re to fly two hours then call it a night in Cambridge Bay.

No. I need off this tin can. Graciously, they let me go.

But in Kugaaruk’s shack of an airport, relief transforms to self-doubt. It’s 4°C, windy and drizzling. Any auspicious feelings leave with the aircraft’s rising, shrinking, and fading image.

Feelings can change. Making a list feels in order, so I do.

1. Borrow the phone and rebook your ticket.

2. It’s hard to be cavalier when you’re cold—dress up, champ.

3. Walk into town and see something new.

Done, done, and airport staffers Wilfred and Daniel drive me into the community. They give me a hot tip too: at 11 p.m. there’s a one-night-only live band playing at the community hall. They also let me know Jesse (my Kugaaruk work colleague) lives in a green house. Fortuitous feelings are back. I remind myself, it’s not an adventure if nothing can go wrong.

I step out into the town a stranger. I’m reminded of my first Arctic days seven years ago, when I arrived naïve and unadjusted to Taloyoak, still the only Nunavut community I know. I feel rejuvenated to see the world as new again, though this time less the tenderfoot.

As before, the kids zero in. “What’s your name?”

“I’m looking for Jesse.”

“He lives in the green house.”

“That’s him.”

We walk. Jesse’s not home. No one is. I walk on. More kids follow. And more kids still. A pickup rolls up alongside. Two becoming young women invite me to share the front bench of the darkened cab. I accept.

“Lots of kids, eh?” one of the women whispers.

Not whispering, I say, “Yes, I was just…”

“Shh… our babies are sleeping in the back.”

Right. “I’m going to the Hall,” I speak softly.

The lasses kindly taxi me to my venue. There’s Jesse and his son, who is in the band no less. In small places, one’s luck is condensed: here, Canada’s thousands of extraneous Jesses have been filtered out. I see there’s a Taloyoak diaspora here, too. Peter, Lucy-Ann, Byron, and Edmond are heading home for this weekend’s volleyball tournament—same flight as me no less. The band turns ‘The Wreck of the John B.’, an old Bahamian folk ballad, into an Inuktitut punk-metal classic. It’s a great show.

The next morning, I get up early for a walk. A long ascent takes me up a river hidden under rocks and overgrown moss. Atop the hill, I take in the view of Pelly Bay (Arvilikjuaq), with multiple islands and an only slightly rippled ocean. Back in town, Jesse meets me for lunch, followed by a driving tour—no babies, this time. Every house, every corner has a story.

Boarding the turbo-prop destined for home, I’m thankful at last—to the flight crew letting me off the plane, for the impromptu taxi ride to the show, and for meeting so many friends, old and new.

Byron and I share a seat row. From the air, we pick out lakes and landmarks below, until Taloyoak’s telltale Sandy Point scrolls into view. We are home now, happier for the stops along the way.