The North's missing son

Johnny Bourassa was the child of famous mail carrier Louis Bourassa, who ran mail through the wilderness of Northern Alberta with such grit that King George V, in Buckingham Palace overseas, made him a member of the Order of the British Empire. Johnny was a war hero, honoured for his conduct as a WWII fighter pilot while carrying out operations against some of the most heavily defended cities in Germany, including Berlin itself. Johnny was a dog whisperer and family man, beloved in Peace River, Alberta, and he earned respect in the NWT when he swam out and rescued two anglers from the frigid waters of Great Slave Lake after a plane wreck in 1949. But on May 18, 1951, he was supposed to land in Yellowknife returning from Bathurst Inlet. And he didn't.

At the time, he was flying for Yellowknife Airways Ltd. and had been instructed to stop mid-way at Salmita Mine to fuel up his Bellanca Skyrocket rather than cart all his fuel for the trip from Bathurst Inlet, because it was expensive to bring more fuel so far north. There had been bad weather between Bathurst and Salmita Mine, so when Johnny didn’t return that day in May, people thought he’d likely set down somewhere to wait it out. On May 20, word came in that Johnny hadn’t stopped at Salmita—he’d filled his tanks up at Bathurst and set off directly for Yellowknife. The air force was called in to search north of Yellowknife, and bad weather prevented them from setting up a grid for 10 days. By June 17, more than 414,000 square kilometres had been flown over by 13 planes that found nothing.

In September, a U.S. air force spy plane went down in Northern Saskatchewan. While searchers conducted a clandestine effort to find this plane, they came across a Bellanca Skyrocket on skis parked on the shore of Wholdaia Lake, about 520 kilometres southeast of Yellowknife, near the border with Saskatchewan. There was no one in it, but Johnny had left a note in the cabin. He wrote that he believed (correctly) that if he headed northwest he would reach Fort Reliance, at the tip of the East Arm of Great Slave Lake. He wrote that when he’d taken off from Bathurst Inlet, he didn’t have maps, the plane’s clock wasn’t working, and his compass was functioning inconsistently. When he broke through clouds and spotted land, he misidentified where he was—and by the time he realized he was way off course, he surmised (again correctly) that he had well passed Great Slave Lake, and he was too low on gas to continue his journey. He set down the plane, stayed for five days hoping to signal someone flying overhead, and then set off after seeing no hope in the skies. He never arrived home and was never found.

Searchers found evidence of a few camps that were likely Johnny’s, as well as a sapling used to bridge a creek and a cut log that may have been used to build a raft, but nothing more. All sort of theories abounded—folks couldn’t grasp how Johnny, an experienced pilot and Northerner, couldn’t have made it further or left more signs. In a book on plane disappearances called Lost, a friend of Johnny’s and a searcher, Neil Murphy, told author Shirlee Smith Matheson, “Johnny just got lost. People credit him with more wilderness survival knowledge than he actually had. His father, Louis, ran the mail and was a river pilot, and Johnny also piloted boats on the river. But they weren’t bush people. He never trapped.” In 1994, Murphy told Up Here he believes he followed Johnny’s final trail.

A hero’s demise

In 1937, one of Soviet Russia’s greatest heroes flew over the North American Arctic, and neither he nor his passengers or cargo were seen again.

Sigizmund Levanevsky took off from Moscow on August 12 of that year, cheered on by thousands, to make a grand flight over the North Pole to land in America; it would be the first cargo/passenger flight of its kind. He was aiming to fit another feather in a hat brimming with plumage: Levanevsky, who fought bravely in the Soviet Civil War; Levanevsky, who rescued an American pilot from an ice sheet on the Chukchi Sea after building an improvised airstrip; Levanevsky who’d already flown over the pole to San Francisco from Moscow—surely he’d do it again.

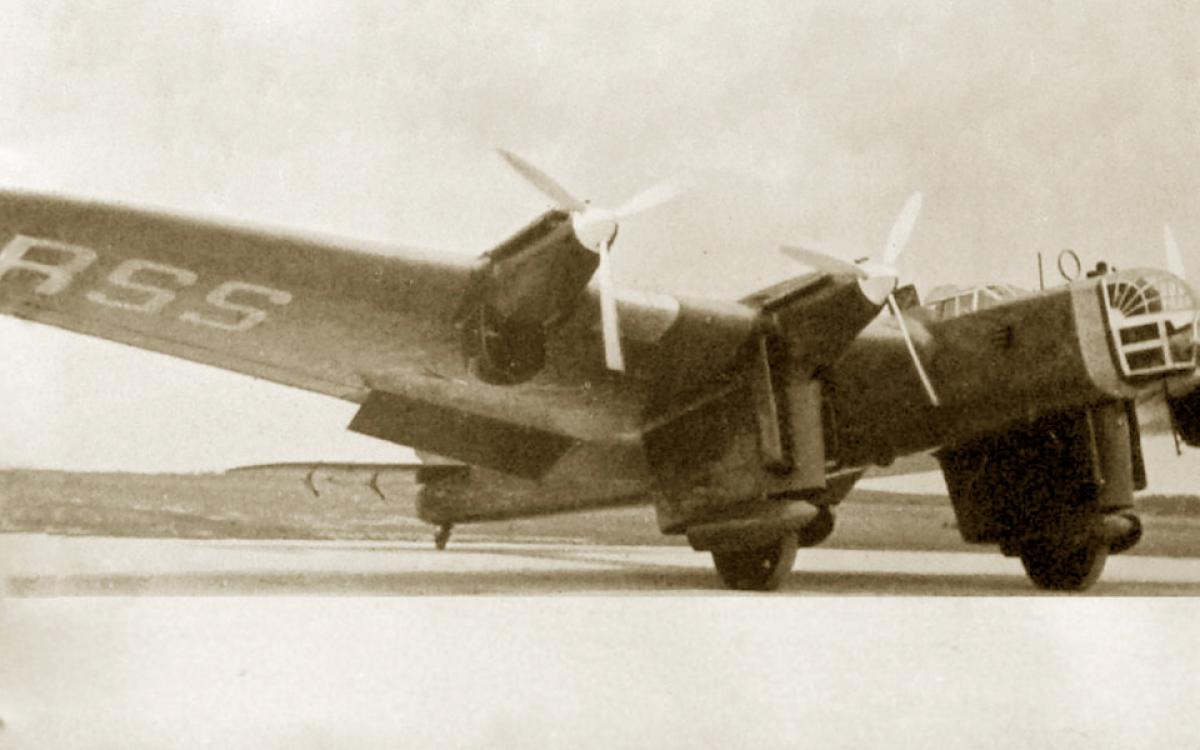

He would fly a bomber that had been converted into a civilian aircraft. According to Yury Salnikov, a member of the Russian Geographic Society and a documentarian, the plane was untested but the official in charge of the project—aiming to please Joseph Stalin, who had a great interest in aviation—gave the engineers three months to prepare it. They would have likely needed a year.

When the four-propeller plane took off, its far-right engine was trailing smoke. While engineers on the ground thought the smoke would soon abate, it didn’t. Levanevsky’s final transmission, 19 hours later, was that the far-right engine had quit and he was going to attempt a landing.

The Russian government contracted a British-born Canadian, Herbert Hollick-Kenyon, to lead two searches for Levanevsky and his six crew, but nothing was found. Polar explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins would look for Levanevsky via seaplane and icebreaker, but found nothing. American crews searched. And when World War II broke out, the search was shelved and would stay shelved.

But Salnikov has hope. Since the ill-fated flight, relations between Russia, Canada and the U.S. have changed dramatically. The camaraderie was long replaced by aggression and tension, which still colour our interactions. But the three are working together to map the Arctic right now; Salnikov hopes the three could join forces and look for Levanevsky’s lost, last flight while they’re at it—cooperating in the search for a great hero, like they did so long ago.

Disappearance and conspiracy

On January 26, 1950, a great American tragedy occurred in the wilderness of the Yukon: a Douglas C-54 Skymaster, with 36 passengers and eight crew on board, simply disappeared.

The plane was flying from Anchorage, Alaska, to Great Falls, Montana, loaded with military members and their families. Two hours into its eight-hour journey, it reported that it had just passed over Snag, Yukon. After that, nothing—not a trace nor any shred of explanation, despite the mobilization of a massive search effort. Seven-thousand personnel and 85 planes, American and Canadian, participated in the search, covering more than 900,000 square kilometres until the search was called off on February 14.

In the years since, interest hasn’t died down. Far-flung conspiracy theories have been developed, specifically centred around an area of Alaska where there have been multiple disappearances. Documented UFO sightings in the area that year buoyed these claims.

The first happened just two days after the C-54 went missing. Lt. Col. Lester F. Mathison was walking between two buildings at the Elmendorf Air Force Base near Anchorage, when he spotted three reddish-orange objects shaped like cigars moving in a slightly curved line northwards, 25,000 to 35,000 feet off the ground. Next, on April 19, two green lights were spotted 200 to 300 feet above a hangar at 1:22 a.m. They moved towards a control tower, glowing and emitting a green trail, before taking off southwest and disappearing.

But more grounded theories prevail: that the C-54's wreckage is indeed still out there somewhere on the ground. A group of people have resurrected “Operation Mike” (the original search operation’s name) and are trying to raise funds to find the fuselage and give the living relatives and descendants of the missing some long-overdue peace of mind.