Humanity’s relationship with polar bears is complex. There are those people, far away from the North, who will never see one in their lifetime but have stuffed bears and picture books of them in their homes; there are the scientists who study the bears and influence policy; there are the bureaucrats and politicians who write laws; and there are the Inuit who hunt the bears. And for a while, they all got along well enough.

But as times changed, other actors entered the stage with loud voices. Scientists said climate change was threatening polar bears by degrading their habitat of sea ice. Climate change activists latched on and adopted the polar bear as the mascot of a warming world. Animal rights activists took it a step further and said the bears were under threat and that they should be classified as such, with legal ramifications for hunting them.

Some prominent Inuit, in defence of the hunt, have allied themselves with climate change skeptics and have turned against the researchers, who are in turn finding it harder and harder to do their work under intense public scrutiny. And the people who live far away and will never see polar bears in their lifetime hop on Twitter and add to the din on both sides.

Amidst all this noise, it’s impossible to get a clear answer on how the bears are actually doing.

“Nobody paid attention to what we said, other than government managers and a few other folks. It was a simpler time. There wasn’t a spotlight on you.”

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time when Inuit, and others, hunted polar bears without as much as a blink of an eye from the rest of the world. Researchers, too, studied polar bears, published their research, and went about their days without much criticism.

“Thinking about early PBSG (Polar Bear Specialist Group) meetings, nobody cared that we met,” says Geoff York, an American biologist who has studied polar bears for 20 years, and has worked on the policy and management side as well. “Nobody paid attention to what we said, other than government managers and a few other folks. It was a simpler time. There wasn’t a spotlight on you.”

The PBSG was formed to discuss polar bear conservation, following concerns about over-hunting of the species in the 1960s. The International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears, which was signed by Canada, Norway, Denmark, the U.S. and Russia in 1973, set protections for polar bears in stone. Hunting rules were established, and polar bears began to rebound in population.

Ian Stirling, a long-time polar bear biologist, was one of those researchers coming up with population estimates in the 1970s and early 1980s. Bigger than expected, they resulted in higher hunting quotas, and everyone—government, Inuit hunters, the scientific community—seemed happy. “I can tell you there was not one person who ever asked me if I was really sure about that. Or any questions about my methodology,” Stirling says.

But over the last 10-15 years, many scientists, including Stirling, have been adamant that the polar bear population is indeed increasingly vulnerable, mostly due to climate change, and some studies have shown drops in numbers. “That was liable to have an influence in reducing quotas,” says Stirling. Hunters, basing their views on their own observations pushed back. “All of a sudden science was bad.”

This divisiveness has made scientists’ jobs harder. Stirling has long lauded the accuracy of traditional knowledge—Inuit stories and obersvations—and used it in his studies. But he’s often placed in a camp that puts him at odds with Inuit. “It’s one of the things that I find most disappointing, is when people think that I’m anti-traditional knowledge, because I’m absolutely not,” Stirling says.

It’s important to understand the Inuit’s connection to the bears. It plays a gigantic role in traditional Inuit spirituality and is integral to their culture and diet. They hunt the bears for food and clothing, and have been able to get a little income—in towns that have almost nothing else going on economically—by taking southerners on trophy hunts and selling parts like the furs.

James Eetoolook, vice-president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI), the group that represents Inuit under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, says that’s exactly why NTI has been lobbying the U.S. to abandon its efforts to ban the trade of polar bear skins internationally. Last May, the U.S. backed off its proposals, but the fact that the most powerful government in the world had taken the issue so far illustrates a frustrating reality: Polar bear researchers, the Canadian government and Inuit all believe a well-managed hunt is sustainable, yet their voices are often drowned out by those of activists who have no direct stake in the animals.

“The work Inuit have done in developing the polar bear management system—you know it’s been 40 years since we started using a quota system—we managed to keep that system in place today,” Eetoolook says. “It is in Inuit interest to maintain the health of the polar bear population.”

But there is another thread of discord still, this time within the scientific community itself. While the majority agree with researchers, there are those who dispute their conclusions.

Susan Crockford, an adjunct professor at the University of Victoria, runs a blog called Polar Bear Science on which she, generally, disputes findings that attribute decline in polar bear populations to the loss of sea ice due to climate change. She is quick to write rebuttals to anything Stirling and other polar bear researchers come out with.

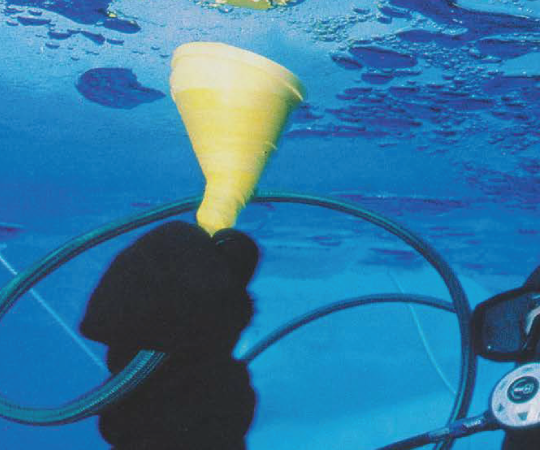

Crockford has not spent any time in the North—something she says is “actually the strength of my perspective,” because on-the-ground researchers can get too emotionally attached to the animals. And she may have a point: Google the name of a polar bear biologist and they’re likely to have a picture of themselves with polar bear cubs, while the mother is tranquilized. It’s a level of contact that Crockford, and many Inuit, are uncomfortable with.

York sees this kind of criticism as one of the benefits of the attention around polar bears. Now, researchers think long and hard about when to intrude on a bear. “It made managers and researchers think really hard about what they needed, what was absolutely necessary information to gather for management, versus what was interesting, and what would be nice to have,” he says. As for the pictures, York wishes there were fewer out there of him stopping to pose with the bears, but says it’s just a by-product of a long career with the bears.

But Crockford’s main criticisms seem more ideologically-driven. She is skeptical of human-caused global warming, and that feeds into her tireless venture of disputing polar bear researchers who contend climate change is a threat to the bears. “I’ve got a lot of free time,” Crockford says. “No one is paying me. Science is my hobby.” That may be the case now, but she has been paid, in the past, by The Heartland Institute—a conservative think-tank known for sponsoring climate change denial. Papers leaked in 2012 showed that Crockford and another Canadian scientist critical of polar bear researchers and climate change, Mitch Taylor (who has been employed by the Government of Nunavut), had been receiving a small monthly sum of $750 from the institute. Crockford said she was paid to provide input on “vertebrate animals,” including polar bears. She rejects any notion that those payments bias her criticism of polar bear researchers.

Despite that background, Crockford's criticism of mainstream science has made her some unlikely allies. Because she is quick to dispute low population numbers, some Inuit have promoted her blog as an alternative perspective, including current Iqaluit mayor and prominent Inuit rights activist Madeleine Redfern. Crockford says several Inuit have contacted her personally in support. This, despite the fact that Crockford is based in the south and does not travel to the North for her research—something southern researchers are often criticized for by Northerners.

"Why not pay attention to an animal population that is declining? It’s big money, that’s what it is. Animal rights groups, they get the money from people that don’t have a clue what’s going on."

This brings us to the next interveners: conservationists.

Most polar bear scientists are not against hunting. Not yet, at least. The PBSG is clear that it believes the main threat to polar bears is the sea ice conditions brought about by climate change. York believes that hunting, if well managed, will not further harm even the most threatened populations.

But it’s hard, says York, to get that across to people who live in urban centres, or even rural areas of, say, Europe that have lost the cultural traditions of hunting—people who think, “Here’s a species that’s threatened. Why would they continue to hunt it?”

Eetoolook says the attention paid by conservationists can make it difficult for Inuit to get their message out. “There are other species that are declining … Why not pay attention to an animal population that is declining? It’s big money, that’s what it is. Animal rights groups, they get the money from people that don’t have a clue what’s going on. It’s just like blackmailing people, for something [they don’t have] any legitimate knowledge [of],” Eetoolook says. The pervasive view that every single polar bear needs to be saved made it that much harder for Eetoolook to plead his case against the United States.

"The broader population doesn’t realize that wildlife is managed worldwide where we have no idea what the numbers are—and never have.”

Polar bear researchers have to walk a fine line: they risk being associated with conservationists and potentially aggravating relations with Inuit hunters, and being associated with the hunters themselves who many southerners see as barbaric. This has hampered science, York says. “The ability for researchers to gather information that managers want or need, became more difficult in some areas ... I think, in a way, it delayed new information from being gathered and brought forward.”

The challenge now for government managers, researchers, and Inuit, is how to have civil discussions in this quagmire. For that, Stirling believes the discussions need to return to the state they were 20 years ago, before things got political.

“We need to go back to that more open and accepting discussion that people aren’t out there to hurt one another or to abuse one another,” says Stirling, “and that we’re all interested in the same kinds of things, relative to sustaining a harvest and sustaining a population of a species that’s having some difficulties.”

York is hopeful. He’s seeing discussions between hunters and managers become more collaborative, due, he says, to a changing of the guard—a new crop of scientists who are willing to present more nuanced reports of health indicators, and Inuit leaders who are warming to the fact that not all scientists want them to stop hunting.

“There’s this total train wreck that happens again and again between the actual science and the interpretation of that through various lenses, and sometimes even through scientists themselves, where complexity and nuance is completely lost,” York says. “I think that happens again and again with numbers. The broader population doesn’t realize that wildlife is managed worldwide where we have no idea what the numbers are—and never have. But we do the best we can from other metrics.” This could mean focusing on the quality of polar bear habitats, or their reproductive rates.

Perhaps then there will be less for the outsiders—the climate change deniers and activists, the conservationists—to sensationalize. And with fewer headlines, perhaps there will be less vitriol. Then, maybe, everyone will stop yelling and begin talking, rationally and seriously, about the bears.

“Growing up, amongst Inuit, we used to talk about not joking around about polar bears, otherwise they can attack you from nowhere,” Eetoolook says. “That has been our belief, so we are taught to respect the polar bears. The Inuit have been doing that—respecting the polar bears—for a long time.”