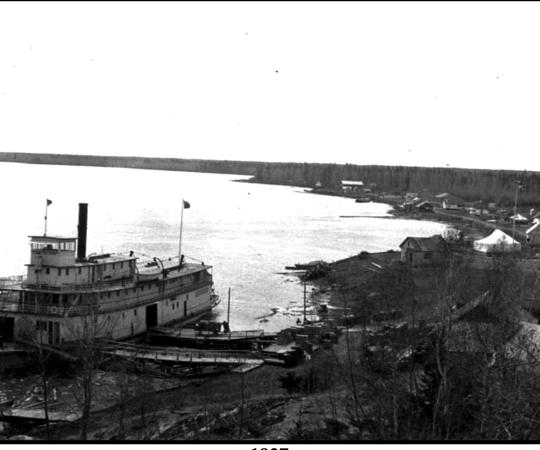

On July 15, 1926, Maurice Haycock stepped onto the Canadian Arctic Expedition’s annual supply ship Beothic in North Sydney, Nova Scotia. He was setting off to join his boyhood friend Ludlow Weeks on a geological survey expedition to the Pangnirtung Fiord area of Baffin Island.

It was a trip that would change the life of my father, who would become a famed painter, historian, and lifelong lover of the Arctic.

Before reaching their ultimate destination, the ship stopped in Nuuk and Etah in Greenland, then Bache Peninsula on Ellesmere Island. Here, Haycock recorded in photographs the opening of Canada’s northernmost RCMP post. The ship stopped at another RCMP outpost, Dundas Harbour on Devon Island, and the nearby site of Franklin’s 1845-46 camp on Beechey Island.

But the true adventure began when he arrived at Pangnirtung Fiord. There, he spent the next year living with the Inuit, travelling great distances on ice by dog team, staying in skin houses (tupiks) and iglus in winter, cooking and heating by seal oil lamp (kudlik), hunting, and eating their diet of seal, walrus, caribou and birds’ eggs. He also took many photographs and learned to converse in Inuktitut. While completing the mapping assignment of the Cumberland Sound and Nettilling Lake area, he came to admire the Inuit and the close connection they had with their land.

When the Beothic returned to bring Haycock home, he met two artists aboard the ship, accompanying the annual supply run on the same route Haycock had taken the year before. They were A.Y. Jackson of the Group of Seven and Sir Frederick Banting, who discovered insulin.

During the two week-voyage south, Haycock spent considerable time with the artists, watching and listening to them describe how they transformed the light, geological features, weather, and sense of place around them into images on their panels using only their paint and brushes.

It was a turning point for Haycock. After his year-long exposure to the successful life Inuit had carved out in a vast and often challenging environment, he realized he had fallen in love with the Arctic. Now, having witnessed the artists’ interpretation of that exceptional land, he also wanted to paint it.

In the years that followed, Haycock completed his PhD studies at Princeton, joined the Department of Mines in Ottawa, and began to seriously paint. He kept in touch with Banting and Jackson. In the spring of 1943, Jackson invited Haycock to paint with him—the beginning of a 30-year friendship and painting partnership.

In 1949, 1950 and again in 1957, when mineral research took Haycock into the Northwest Territories, Jackson joined him at Great Bear Lake for lengthy trips into the Barrenlands, returning by air to Lake Athabasca in the fall.

But Pangnirtung, which Haycock called “the most beautiful place in the Arctic,” was his first muse. Haycock’s earliest paintings, from his photographs, were looking up Pangnirtung Fiord, 1936-38. He last painted there in 1987.

Haycock first returned to Pangnirtung in 1960, when his work took him to the Nanasivik mine site near Arctic Bay. He would stay at Pangnirtung en route and visit old friends Simon Shaimayuk, Jim Kilabuk and his family, and many others. Kilabuk had assisted Haycock with surveying decades earlier and remained a close friend. In 1926, Shaimayuk had been a youngster who had just lost his parents when Haycock arrived. (Haycock also lost his parents at a young age.) They enjoyed many visits over the years as Shaimayuk developed as an accomplished artist at the Uqqurmiut Centre.

Whenever Haycock visited Pangnirtung, not only did he paint in the community, he also shared a slideshow of photographs he had taken in 1926-27, and during subsequent visits. People recognized themselves and others. Young men and women from his first visit had become elders. Elders who had passed on were remembered as community leaders. An infant in one photo now had her own children. The slideshows were hugely popular. Many of Haycock’s photographs are in the Pangnirtung museum archives to this day.

When my sister Karole and I were little, our dad always told us stories about his time in Pangnirtung until the names of people and places and the ways of life became familiar to us. In retrospect, these stories are part of our Haycock family oral history.

After my father retired in 1966, his annual trips north became longer—taking the entire spring, summer, and a good part of the fall. Travelling from Iqaluit to Resolute Bay, he was sure to always stop at Pang to renew beloved friendships and experience the magic of the fiord.

Resolute was the hub for flying out to numerous Polar Continental Shelf Project (PCSP) research camps. Haycock visited them all, contributing to everything from cook-tent duties to aiding with research, and provided a painterly perspective of their camp surroundings. There are many large canvases by Haycock depicting various PCSP camps on display in numerous boardrooms at Energy Mines and Resources in Ottawa.

In 1969, Haycock was part of a team, led by Dr. Fred Roots, working at the North Pole to measure “polar wobble,” as it would affect possible Russian intercontinental missile trajectories during the Cold War. Haycock used his HAM radio set to send and receive data to and from a processing computer in Minnesota. (Data from that research forms a part of your current GPS device.) Of course, he painted there—he’s the only artist ever to paint at the North Pole until 21st century Arctic cruise ships plied their way to the pole with passenger artists.

Haycock was smitten by the Arctic. He felt very privileged to have joined the Inuit of Cumberland Sound for a year and experience traditional life on the land. His interest in the region’s history grew into a quest to locate and paint a collection of plein air (on-site) paintings of important historic sites. He visited and painted the earliest Cape Denbigh culture at Engigstciak in the Firth River Valley; Dorset and Thule sites on Ellesmere, Somerset, and Bathurst Islands; Norse sites; and the many encampments of the British explorers who followed.

He painted his way all over the Arctic—travelling by air, ice breaker, dinghy, local four-wheeler or truck, and many, many miles on foot. One site he visited and painted often was Beechey Island, which he first visited in 1926. After John Franklin’s expedition overwintered in 1845-46, the site was subsequently used as a base encampment by numerous search parties looking for him. Extensive mapping of many Arctic islands’ coastlines was a huge accomplishment though Franklin’s fate was not found.

Haycock’s research into the journals of these Arctic explorers led him to suggest and help locate a sunken ship, the Breadalbane, off Beechey Island on a search organized by scientist and deep-sea diver, Dr. Joe MacInnis. Haycock also liked to visit and paint Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island, but was dismayed by the removal of many artifacts left behind by Greely (1881) and Peary (1898, 1909) who camped there on their quests to reach the North Pole.

In 1980, Haycock was the recipient of the Massey Medal, awarded by the Royal Canadian Geographic Society for his contributions to understanding the history and geography of the Arctic.

Forever grateful to Jackson for introducing him to painting, Haycock built a large cairn to commemorate his friend’s love of the North. Originally, he had intended to erect the cairn at the Bache Peninsula—the most northerly spot Jackson ever reached to paint. But in 1968, ice prevented Haycock’s ship from reaching it, so instead he built the cairn at nearby Alexandra Fiord (and scratched “NEAR” into the brass plate he had prepared where it said “AT”).

Maurice Haycock lived from 1900 to 1988, leaving a legacy of Canada’s Arctic geography and history told with warm, visual honesty and sensitive feeling.