Bernice Clarke, founder of Uasau Soap in Iqaluit, spins a tuft of Arctic cotton along the edge of her kitchen table, pulling at the soft fibres to make a wick for a qulliq. Narwhal oil, she’s been told, is best for lighting the traditional soapstone lamps, burning more brightly than oil from other Arctic whales. Fans of Uasau’s line of whale-oil soaps and lotions also tell Clarke it’s a skin-saver—something greatly appreciated through the long, dry Nunavut winter. The star of her product line, though, is bowhead oil. “The bowhead is for healing,” Clarke says. “That was chosen as the medicine.”

Today, Uasau continues to operate from Clarke’s home, though much has changed from its humble start. In 2012, Clarke took a table at a craft fair, selling body butters that she had made. She sold out—and left the event with a list of customers who promised to make regular orders. With help from her husband and business partner, Justin Clarke, she moved on to making soap and developed a logo that uses the tails of amautis for the two Us in the company name. The whale oil came later, at the suggestion of a friend who knew that bowhead blubber was a traditional Inuit treatment for eczema.

The duo now sources more than a year’s supply of soap base at a time, from the same distributor used by the popular soap brand LUSH. They mix that base with whale oil and natural exfoliates gathered in Iqaluit summers, such as tundra moss, dried flowers and seaweed from the bay. “People want it. People are starving for it,” says Clarke, who now markets Uasau products through Facebook, craft fairs, and a handful of retail outlets. “It’s based on my culture. It’s part of what we used for hundreds of years and it was taken from us. We're reclaiming it. It’s healing for Inuit to hear we have bowhead in our soap.”

The story of Uasau is compelling in its own right. After all, it draws together several themes central to successful entrepreneurship: creativity, attention to customer wants and innovation, notably around integrating whale oil with soap base. What makes it more interesting, is that it’s just one of a growing number of new businesses in Nunavut started by women.

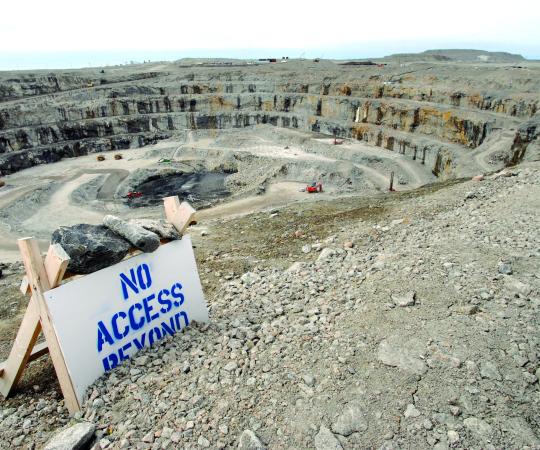

The territory’s economic climate is certainly supportive of new ventures. Mineral investment is driving sustained growth, a trend that is projected to continue for at least the next five or six years. Unemployment, meanwhile, is projected to fall, although it will remain well above the national average. Economic good times, however, are no guarantee that a new business will succeed. The edge that’s helping these entrepreneurs find their markets is a genuine desire to express Inuit tradition and values, and in doing so, foster positive messages and community pride with products and services that resonate with Nunavummiut.

Coral Harbour jewellery designer Adina Tarralik Duffy is a case in point. After tinkering for three years with a personal passion, she launched her company, Ugly Fish, in 2012 with a jewellery line featuring materials such as baleen, narwhal and walrus tusk, caribou antler, polar bear fur, raven feathers, seal claws, and even ptarmigan feet. Since then, she’s become best known for jewellery incorporating spinal disks from beluga whale. She cleans the disks of flesh and sinew, and then fashions them into earrings, necklaces, and cuffs.

“I never intended to start a jewellery business,” Tarralik Duffy says. “As the jewellery sold, as the business grew, I followed it. It happened naturally...My problem is having stock. It sells out so fast.”

Tarralik Duffy ships her “found bones” north and south to retail outlets that range from the Winnipeg Art Gallery to the Kuugaq Café in Cambridge Bay. She’s shipped pieces internationally, too, but sticks to Canada with beluga due to international restrictions on trade in marine mammals parts. Not that such restrictions worry her. Or Clarke. “Our market is Inuit and people who want to be part of our culture,” she says.

The same sentiment is at the core of the Arviat and Baker Lake-based Hinaani Designs, which makes casual fashions and accessories. “Our purpose is for our home,” says Emma Kreuger, who runs Hinaani with her partner Nooks Lindell, his cousin Lori Tagoona and their long-time friend, Paula Ikuutaq Rumbolt. “Our focus is on social impact more than financial gain.”

That goal is literally represented in the products Hinaani creates, such as leggings printed with phrases that promote positive thinking and community pride in local Inuktitut dialect: “ajunnittunga” (I am capable), “arnaujunga” (I am a woman) and “nagligijaujunga” (I am loved). “When we started the business, one of our main goals was to build pride in our Inuit culture,” says Rumbolt who, as an Inuktitut instructor, looks after language at Hinaani. “We make sure that whatever we produce has that focus.”

A business benefits when its products and services reflect the lived experience of a client. That’s why Iqaluit’s Elaine Lavoie is working with local graphic designers and photographers to push Nunavut-relevant imagery, artwork and even hashtags as she promotes her new bookkeeping business, Aiviq Financial Services, through social media. Her Instagram feed touts financial advice and business support using Inuktitut syllabics, Northern animal memes and imagery from her home office. “Take advantage of the resources in town,” Lavoie offers as advice to aspiring business owners. “There is a lot of help out there, and there is a lot of help for Inuit.”

She sees first hand how easy it is for local start-ups to feel overwhelmed by budgeting and finances. But she’s also excited to be working with other small businesses in Iqaluit’s expanding economic climate. “There are so many businesses starting up, even in the last 10 years the town has changed,” she says, citing a new airport, aquatic centre and a café (where you can finally order a decent cappuccino). “It’s getting to be more like a city. It’s neat to be part of that growth.”

Despite that development, infrastructure is still a huge hurdle for business owners in Nunavut. “The cost of doing business in Nunavut is high,” says Eva Aariak, owner of the downtown Iqaluit boutique, Malikkaat. “It’s very hard to find suitable retail space that is affordable to the business that you have.”

Malikkaat’s tagline is “All things Inuit,” and the shop shelves are packed with carvings, fur mittens, and Inuktut language books. The idea for the shop came to Aariak in the early 2000s, during a trip to Nuuk. “I walked into this little gift shop in Greenland and there was a small qulliq lit as you enter,” she said. “I thought, ‘Wow. This is something else.’ I knew there was nothing like that in Nunavut at the time.”

Malikkaat opened a few years later. The store remains a side project for Aariak, who also works for the Qikiqtani Inuit Association. (She’s also served as Nunavut’s Languages Commissioner and as its premier between 2008 and 2013—at which point she took a hiatus from retail.) While large-scale business remains male-dominated in Nunavut—mostly in mining and construction—Aariak says, “In terms of Inuit arts, it’s the women who are taking it on...I’m very proud of women who are up and coming entrepreneurs.

You are beginning to see that more and more—younger generations with their beautiful designs, stemming from traditional designs.”

Barbara Akoak is one of those women. Originally from Cambridge Bay, she now lives in Iqaluit where she runs Inuk Barbie Designs, working occasionally from the shop of Matthew Nuqingaq, a well-known silversmith. A graduate of Nunavut Arctic College, Akoak’s sterling, brass and copper jewellery is engraved with patterns inspired by seal markings and traditional Inuit tattoos. As an entrepreneur, Akoak says one of the most important lessons she’s learned is the value of setting prices that show respect for her own work. “The amount of time you spend crafting your skills and working on your art is important,” she says. “You should be able to name your price... if you market and brand your name and do it from a good place.”

In 2011, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada launched its Inuit Women in Business Network in an effort to promote business skills and aptitude. What started as a series of workshops on financial literacy has since grown to a community of more than 140 members from across Canada’s Inuit regions. And while the network’s focus is mentorship and professional connection, the project is also able to push culturally relevant business support to Inuit women as they navigate employee payroll, insurance and tax season.

But the Inuit Women in Business Network has always worked with modest funding. Now, Pauktuutit is looking to teach Inuit women business owners how to submit proposals to commercial and government development projects and procurement markets in industries such as mining. In the meantime, Pauktuutit will keep running business workshops and keep connecting potential entrepreneurs with mentors who have already proven that success is possible.

For all the positive impacts of the program, no amount of support can lift the challenge of trying to launch a business while keeping up with running a family and holding down another job. Uasau’s Clarke, a mentor with the Women in Business Network, knows the challenges well. It takes a lot to balance a day job, side gigs and an eight-year-old at home, with a blossoming career as an entrepreneur. “We’re not just juggling anymore,” she says. “We’re doing acrobatics.”

A few neighbourhoods over, Sadie Vincent-Wolfe, owner of the Iqaluit catering company I Like Cake, speaks to the very same issue. The 35-year-old mother of five said goodbye last year to a downtown cake shop and café that she’d run since 2013. “It was getting so busy I was resenting it. Which is a great problem,” she says.

Vincent-Wolfe now works from her home kitchen, which lets her pick which cake and catering gigs will fit her schedule. She’s also planning to revamp her cabinets and countertops, and install two industrial stoves she scored at the closing sale of an Iqaluit restaurant. “We find everything locally and second hand. I’ve never bought a new mixer, but I have five,” she says. (Her steel baking tables are out of Iqaluit’s former Subway franchise.)

Vincent-Wolfe’s financial discipline is laudable, but it pales against her apparent skill at time management. A few years ago, she was hired to cater the Iqaluit tryouts for the Arctic Winter Games. She wasn’t feeling quite right at the beginning of the day, but she pressed on and, after wrapping up the day, made a beeline for Qikiqtani General Hospital, where she delivered her son, Silver. “I knew when we started breakfast that I was in labour,” she says.

Jenn Lindell, owner of Jeen87 Hairstyling, is another entrepreneur who’s forsaken a storefront to work from home. In addition to having more time to spend with her family, she’s created her own salon space—one that’s connected to the city water line, eliminating her need to rely on trucked water services, as she has had to do in the past. She’s even designed the space for later expansion into a full spa.

Back at Uasau, the Clarkes are working to reinvest revenue into their small manufacturing needs—like industrial melting pots, moulds and labelling. Because her family runs a skincare line, Clarke made sure to incorporate the business, to protect her family finances. “If we didn’t have the passion we would have stopped,” Clarke says. “We believe in it so much. We put our family, love, energy, soul into this company.”

Already mixed and poured, today’s batch of soap will need a few hours to harden before it’s ready to box. That leaves time to snack on bowhead mataaq that’s thawing on Clarke’s kitchen island. With an ulu she scores the fleshy pink fat, cutting off thin slices of the thick black whale skin. “It has become about celebrating my culture and showcasing Inuit,” she says of Uasau Soap. “Everything is about the old way, and we’re bringing it back into a new way.”

Uasau struggles to get soap base into Nunavut without paying high shipping costs, but sourcing bowhead oil is the company’s greatest challenge. The marine mammal is hunted only sparingly, and only by Inuit. Narwhal and beluga aren’t as hard to get, but those animals still have to be hunted, and by Inuit. Any way you frame it, whale oil is a specialty item.

But that challenge can lead to happy surprises.

At an annual sale just before the December holidays (where the Uasau table was all but swarmed) one father stopped for a bar of soap and a brief conversation with Clarke. “This is the bowhead my son caught,” he told Clarke.

He was referring to a hunt from last summer, when Iqaluit residents harvested the first bowhead whale captured by the community in seven years, and the second one in a century. Clarke realized then the soap she was selling for the holidays was part of that community event—part of food sharing and of cultural transfer between generations.

“This is a big thing,” Clarke says, reflecting on the moment. “It becomes part of that story. We should have celebrated that more, we should have screamed it out.”