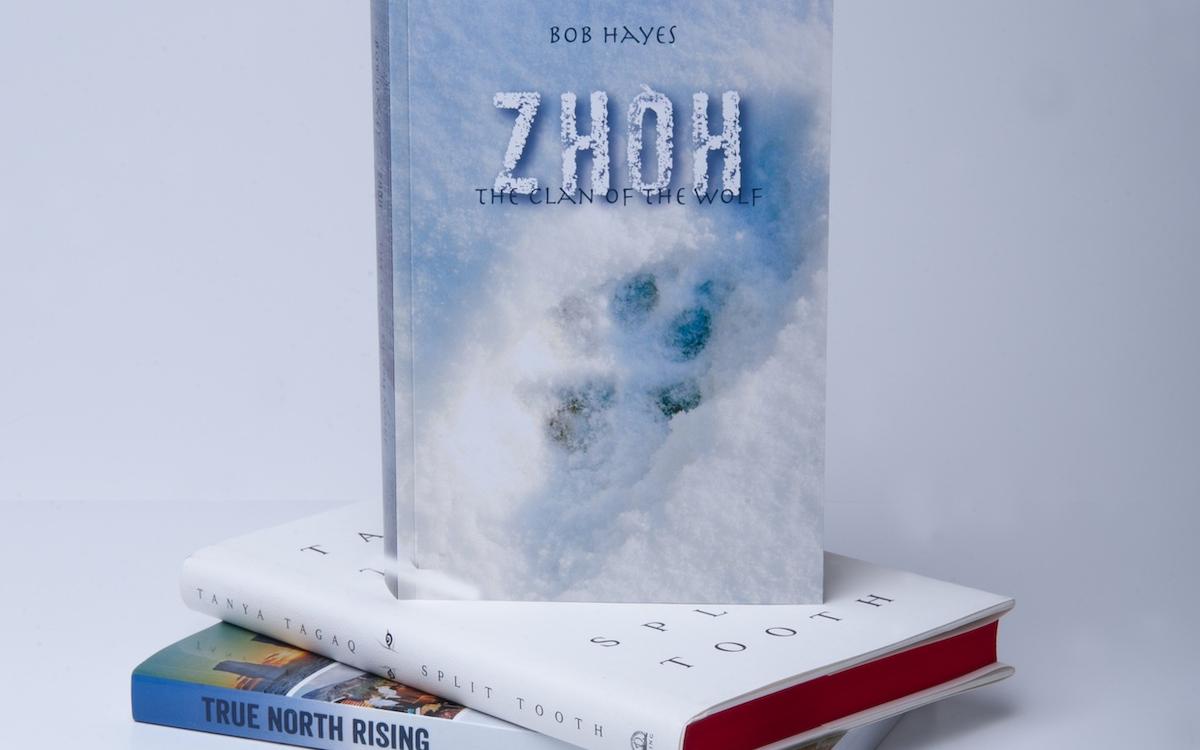

Split Tooth

Tanya Tagaq

Viking Canada

The debut novel from internationally renowned experimental vocalist and artist Tanya Tagaq takes readers into the interior life of a teenage girl in the 1970s living in a small Nunavut community. Captivating and instantly absorbing from the first page, Split Tooth was longlisted for the 2018 Scotiabank Giller Prize and nominated for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award.

In lyrical and searingly honest prose, Tagaq’s writing is rooted in memory and illuminated by wisdom. Tagaq reveals riveting adolescent memories and heartbreaking landscapes such as the Arctic tundra with perfect timing. “We were surrounded by shale rock, dry and sharp under the feet. The clean and hollow crack of walking on shale is still one of my favourite sounds.”

Some tales are entrancing, demented, and sensual, like a dream. Tagaq uses transcendent Inuit tales to shine a light on the politics in Nunavut, like the tale of the Mother of the Sea. “What will Sedna do when she hears the seismic testing?” Split Tooth is as unpredictable and inspiring as love itself. She includes poetry and drawings throughout the novel—a mix of autobiography and fiction—while never giving everything away all at once.

With an achingly raw narrative, this is a story that would shock you if you heard about it on the news. “Watch out for the old walrus/The old man likes to touch young pussy,” she writes. Tagaq has taken on rape itself as a subject, with truths I have hungered for, but never before read. I was not prepared for how the protagonist becomes tougher and wiser. As she says, “I am not six years old anymore.”

With unique strength, Tagaq acknowledges evils like rape, violence, and alcohol and drug abuse with blatant honesty and acknowledges darkness without it being evil. “These foxes will die of starvation; better to put them out of their misery.” Split Tooth is an emotionally resonant novel that will stay with the reader long after finishing the last page. —Katherine Takpannie

Zhòh: The Clan of the Wolf

Bob Hayes

In his debut novel, long-time Yukon wildlife biologist Bob Hayes takes readers back 14,000 years ago to an ice age when the frozen flatland of ancient Beringia covered most of what is now Siberia, Yukon and Alaska.

Zhòh: The Clan of the Wolf tells the story of Naali, Kazan and Barik, three youths who are alone and on the run after tragedy befalls their family clans. Along for the journey is a wolf cub Naali takes under her wing after a bear destroys the cub’s den and eats her siblings.

Part of the novel’s strength is the relationship between humans and animals who form the clans and packs that come to rely on each other for survival in an unforgiving climate where grass eaters like caribou and mammoth are becoming scarce, and ferocious lions are always lurking nearby.

At its core, Zhòh is a story of stewardship, of community and of knowledge sharing—but it’s also a story that carries all the ingredients of any good mythological adventure: brave hunters, wise shamans, a girl who speaks to wolves, and a ruthless, one-eyed giant whose heart is as cold as the snow.

The nomadic people in Hayes’ book are fictional, but his use of language, myth, and spirituality are based on that of the Vuntut Gwitch’in First Nation in consultation with the Yukon First Nation’s heritage committee. Tools and technology used by this imagined people of the Pleistocene Epoch (the last glacial period) are crafted through research and interviews with Northern archaeologists and palaeontologists. Vivid descriptions in the book of Arctic wolves and how they move on the land flow from Hayes’ own fieldwork.

The Clan of the Wolf story continues in Hayes’ second book, Zhòh: The Spirit of the Wolf. —Beth Brown

True North Rising

Whit Fraser

Burnstown Publishing

Whit Fraser’s new book True North Rising is both a memoir of his work as a CBC journalist covering some of the biggest political moments in the North, and a history lesson as told through profiles of the integral figures that shaped the region. “It is one thing to make history. It is something else to challenge and correct it,” he writes at the end of a chapter about his friend Tagak Curley, a central figure in the creation of Nunavut.

To his credit, Fraser seems aware that journalists are rarely as interesting as the people they cover. Rather than challenge history, he maintains a reporter’s unbiased outlook and adds to the historical record. While most chapters are ostensibly about the major stories he covered—the Berger Inquiry is a central event throughout—the behind-the-scene anecdotes serve as mini-biographies of the politicians, activists, and other major players in the territories, some of whom would become his life-long friends. Some of his strongest prose features the story of Mary Simon, who is an influential Inuk leader and Fraser’s second wife, and her family. Elsewhere, Fraser writes fondly about friends and colleagues such as Jose Amaujaq Kusugak, Stephen Kakfwi, and Jonah Kelly.

The stories about the young Indigenous leaders and agitators fighting for self-determination in the North are among the most interesting in the book. Fraser writes about Kelly translating Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech into Inuktitut for CBC Northern Service when the civil rights leader was assassinated. “Jonah captured the emotion of the assassination at the time as he linked the struggle for self-determination to his listeners in the North.”

When Fraser puts the spotlight on himself, he does so with a reporter’s objectivity. A particularly moving chapter recounts his early days as a reporter in Yellowknife and a reckoning with his alcoholism. “I worked to drink and I drank to work,” he writes, remembering hearing his own voice on the radio after a bender. “It was terrifying: I had no recollection of gathering, writing, or filing that story. It was as much news to me as anyone else…It was my voice I was hearing. And this happened not once, but twice.”

Fraser has long been sober. His clear recollections from a distinguished career are a valuable history of the people behind some of the North’s most important stories. —Jeremy Warren