There is a series of trails through the Mackenzie Mountains that were used by people of the Mackenzie Valley and the Yukon to hunt, to visit each other, to trade and to inter-marry. As the raven flies it’s about 500 kilometres from Tulita, NWT to Ross River, Yukon, but with the zigs and zags of mountain passes, and the interruptions of meandering rivers, their annual hike would likely have been 800 kilometres one way. Each year there would be a group of perhaps 10 to 20 people—either the Kaska Dene from Ross River coming east, or the Dene from Tulita heading west.

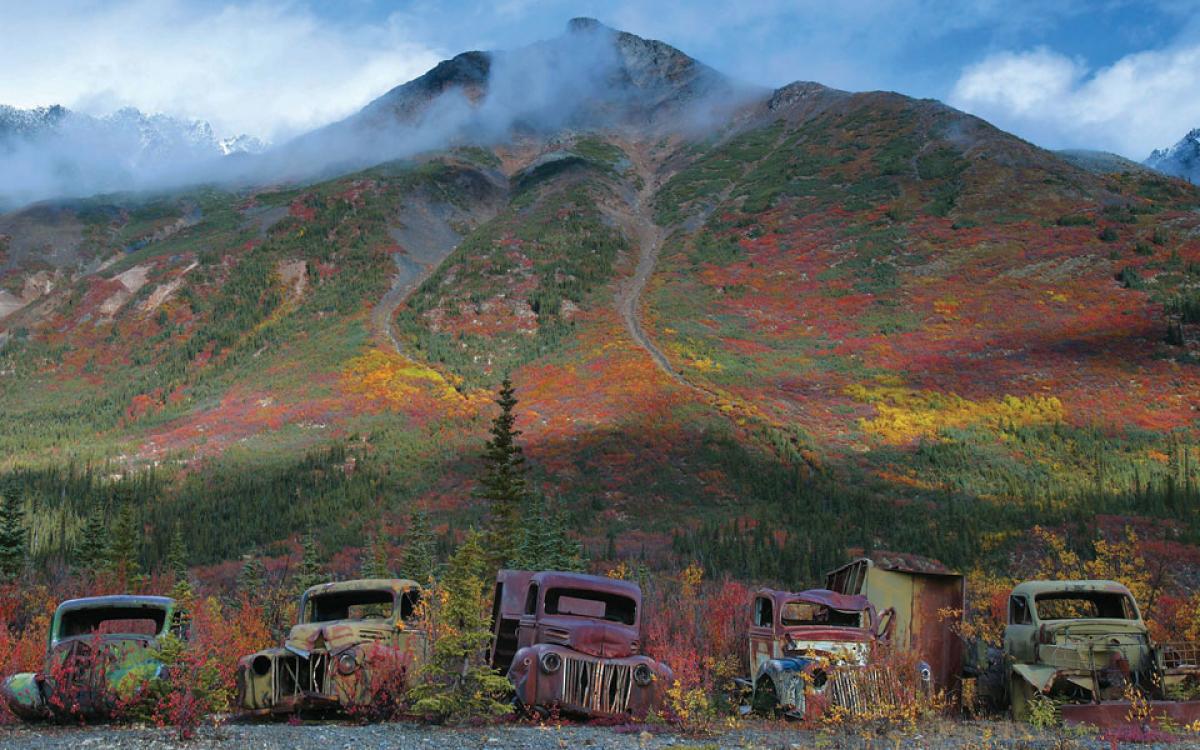

Many of those old trails were linked together during the Second World War through what became known as the CANOL Project. While the Americans built a highway through the Yukon to Alaska, they also developed a way to transport Canadian oil from Norman Wells to Whitehorse and on to Alaska to support the war. The Pentagon was smart enough to hire Guy Blanchet, a Canadian surveyor with considerable northern experience, to map out the route.

Blanchet, in turn, was smart enough to hire indigenous people from the region who had actually used the trails and knew how they connected to each other. The pipeline was barely used before the war ended and the whole project was shut down. Hikers from around the world have used the trail ever since. And starting in 2006, indigenous youth from the Mackenzie Valley have hiked the trail—reclaiming the route, walking in the footprints of their ancestors.

To go from point A to point B without any real purpose is not the traditional indigenous way. We would travel to look for a moose or to make a trapping camp, but just to hike is not really our thing. So when then-NWT premier Joe Handley and I were drafted by then-local MLA Norman Yakeleya to help him develop a youth leadership program within the trails in 2006, we hired two hikers from southern Canada to show us how to gear up for a 20-kilometre-a-day hike in the mountains. Not many of us, or the youth we’d take on the next 10 hikes, were used to carrying all our food on our backs instead of hunting, fishing or snaring rabbits as we moved through the land.

The youth—close to 100 over the last 11 years, and mostly indigenous—are from the region around Sahtu, or what many Canadians know as Great Bear Lake. They are chosen by the program leaders in discussions with other community leaders such as elders, chiefs and teachers, who have opinions about why a particular young man or woman ought to be invited along.

Our gear is modern, which we think likely makes it easier for us than it was for our ancestors. We carry everything we need. In the old days the fastest travellers would have rushed ahead, made a camp, set some snares, perhaps harvested a caribou or moose and made dry meat. We don’t shoot anything to eat, though we do carry guns as this is grizzly bear country. But shooting is a last resort. Our first choice would always be to use our bear spray, which we have lots of. I’ve wondered many times what the ancestors would think about our gear, our nylon tents, freeze-dried food and bear spray.

We cross the many rivers on foot when possible. One year it rained for the first few days of our hike and when we got to a river we could see the water-level rise before our eyes. We had planned to cross that river back and forth over the next several days to stay on track and on schedule. We called for a helicopter to take us back to town. In the old days, the people would have set up a camp, set some snares to get food, and in a week or so, after the flood had subsided, continued on. But we didn’t have that kind of time.

Even while we waited, the water threatened us. Over the next four hours, with three trips by the same helicopter shuttling youth and leaders out of that spot, the campfire had to be moved time and time again and eventually had to be re-made up on the bank above the flood plain. The water flow had increased perhaps ten-fold.

The rivers along the trail are typically three- to five-feet deep when flooded, and because there is a huge volume of water in a flat riverbed, the strong flow makes it hard to stand up once the water is over your knees. (Just last year a hiker, not from our group, drowned when crossing one of the rivers.) To make these crossings, the ancestors had to work together. First, they would find a big, dry log. Gear would be tied onto the log with babiche, as would the young children and babies. Then the men and women in the group would hoist the log onto their shoulders and cross the river. There was no other way to achieve a stability like that, with many feet on the riverbed, like a giant centipede.

The leadership skills that are gained by the youth are real. They have been able to casually connect with a past premier and other leaders from government and industry, in a shared experience hiking along hour after hour, or sitting around a campfire at night discussing important issues. I’ve seen youth come into their own on these trails. One youth who has been on the hike all 11 years, Myles Erb, has gone on to be the community recreation leader for the Town of Norman Wells.

Even if we are not taking the same time and the same risks, and doing all the same activities, being here puts us in the ancestors’ footsteps and allows us to connect with them, and with each other. After all, it was not too long ago that our ancestors walked these trails: the grandmother of founder Norman Yakeleya, Harriet Gladue, made the long trip from Tulita to Ross River and back again on foot three times in her life.

Each year we begin and end our hikes with a tobacco prayer to allow us to focus on how we are hiking with the spirits of our ancestors.

Garth Wallbridge is an indigenous lawyer and educator who has spent most of his life in the North. He is writing a book about the Canol Trail Youth Leadership Project and hopes to publish it soon.