Jimmy Manning has moved a lot of carving boxes in his lifetime. As an art buyer in the 1970s and later as studio manager of the famed West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative in Kinngait, as Cape Dorset was then known, he would sometimes pack and ship as many as 30 triple-walled boxes out of the Nunavut community each month, destined for galleries and collectors across Canada and around the world. “Anything that would come through the door was bought in the co-op,” says Manning, who at 76 has now worked for the cooperative for about 46 years. “It was very important that we buy these works and we collect them.”

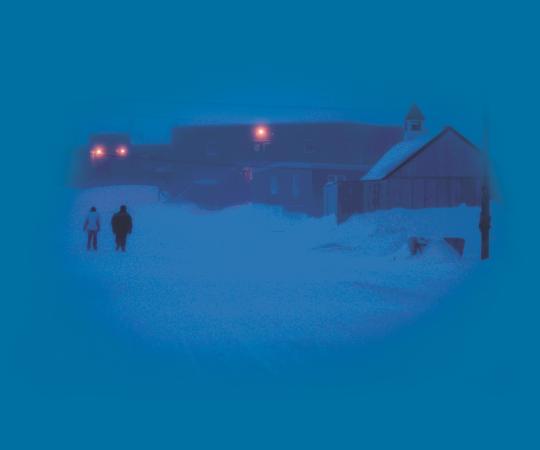

When interviewed, Manning often tells stories from his childhood in Kinngait—peering through the windows of the co-op’s small wooden art shop, the smell of stone, dust and paint. And there are plenty of interviewers eager to hear them this year as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-op celebrates its 60th anniversary.

Manning happily obliges with time-honoured tales of an organization that began in 1959 as a way to bring cash income to a remote community on the southwest coast of Baffin Island and became the epicentre of the international Inuit art phenomenon. But in light of this milestone, he has another story he wants to share: a story about the future of art in Cape Dorset as a younger generation step up to fill the shoes of Dorset giants—like Axangayuk Shaa, Qavaroak Tunnillie, and Kenojuaq Ashevak.

In newer artists, Manning is seeing a thematic move away from traditional Inuit motifs—dancing animals, shamans, camp life—towards more modern and human expression. “It’s very different but it’s outstanding,” he says of the new art. “The younger generation is not shy to express what their feelings are. You see it in the works. They’re trying to tell the outside world.”

Examples of this new voice will go on display at the end of this year when the co-op launches a collection called “Living Legacies” on an international tour. The exhibition, according to marketing lead Will Huffman of the cooperative’s Toronto satellite office Dorset Fine Arts, will be a “calling card” to galleries, museums and collectors who will want to deal in Dorset art in the years ahead.

Living Legacies will also be the first collection crafted solely in the cooperative’s new $10.2-million Kenojuak Cultural Centre, which opened in September and is named after the iconic Kinngait artist, Kenojuak Ashevak. The centre’s state-of-the-art printmaking technology and upscale production workspace reflects the calibre of their globally celebrated product. “It’s palpable-—the excitement, how thrilled they are to have the quality of space that they do,” Huffman says.

Huffman calls the old studio a “functional but rudimentary space” that was “cobbled together” using leftover buildings. “Things were reused, things were makeshift, things were patchwork.”

Looking out the windows of the Kenojuak Cultural Centre now, you’ll see gorgeous vistas of a landscape that has long inspired the carvings and prints that come from Cape Dorset. But if that view wasn’t there as a reminder, a person could think they were in any “high-tech” art studio in the world, Huffman says.

For Cape Dorset, the co-op is about more than art. “It’s one of the most significant economic engines for the region,” Huffman says. “The artists who sell to us have a relatively steady wage they can count on.” The production side of the co-op sees around $2 million in revenue each year and half of that goes directly to pay artists. Another $400,000 goes to art-related salaries in Kinngait and Toronto.

Because the co-op also runs a retail arm for groceries, hardware and diesel, it’s been able to keep its art production afloat during market downturns, or, in the early days, when federal grants ran out. It is also a financially self-sustaining organization and revenue goes back to community members who are registered as shareholders. “The members are the ownership,” says co-op board president Pauloosie Kowmageak, who highlighted this anniversary as a time to acknowledge the benefits the co-op brought to his remote community.

Even in the early days, the co-op's benefits were apparent. Kanaganinak Pootoogook, a renowned local artist and one of the co-op’s founders, saw it as a way to create a financial agency for his community. “A co-op would help the people even more than the Baffin Trading Company, for now the people were no longer poor and could help themselves through the co-op with carvings and prints,” he wrote in a book he co-authored in 1973 with artist and long-time co-op general manager Terry Ryan.

Pootoogook was a mentor for Jimmy Manning, who saw first-hand that community vision grow to an international scale when he travelled throughout Europe as a translator for Dorset artists launching shows overseas. “My strong vision was to make sure that we connect with the artists, connect with the south and maintain the art that comes from Cape Dorset.”

To that end, Manning is thrilled to have a showroom and gathering space at the Kenojuaq Cultural Centre to share new and archived works. Through new windowpanes in that space, visitors today can look in on the studio floor—as Manning did in his youth—to see artists and printmakers fashion a product that, thanks to the co-op model, still holds the same grassroots significance Cape Dorset art had for the remote community six decades ago.