I’m lying in bed, looking out the window at the still night, at the frozen rock and frozen trees, the headframe out in the distance, and realize in horror that I’m going to die one day—as will everyone I’ve ever known—and there’s nothing I can do about it. The reverberating cranks and clangs from the nearby mine’s mill are a nightly soundtrack as I work my way through this.

* * *

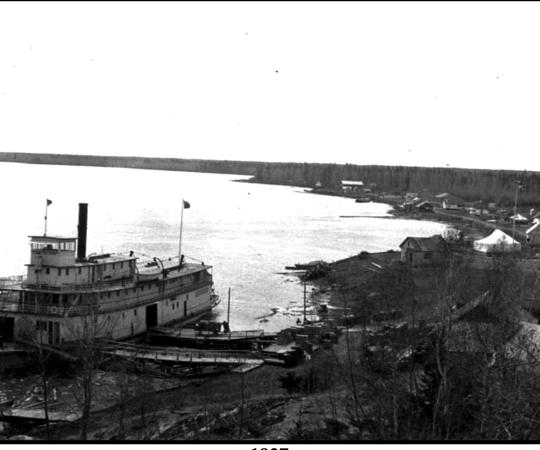

I’m standing on the top of the red, white and blue-black headframe, the tips of my fingers are tingling. We can see Yellowknife’s contours—and miles and miles outside them. My uncle picks me up and pretends to hang me over the side of the 250-foot tall structure. Is this a real memory? Or a dream? It must be a dream.

* * *

We’re sitting in the backseat of our stuffy black 4Runner after school, waiting patiently in the parking lot, watching workers exit the building at the end of their day-shift. Some race out minutes after the first cage arrives on surface, others leave together—laughing—and finish smokes by their trucks. There’s a seemingly endless stream of men that leave the building, after spending their day underground. I squint at each man, each group that walks out, to try to recognize my dad.

* * *

We circle the city in a snowstorm, pulling up and then falling in the sky in a Buffalo DC-3 crammed with hockey bags, players and parents. Half the passengers are having the time of their lives, the other half (myself included) are ghost white. I catch quick glimpses of the headframe through the blur of white outside and the condensation from my thin-breathing on the window. We land and I never again take the ground for granted.

* * *

* * *

I’m done high school and driving back into town after a weekend out camping. I’ve got electricity coursing through my body, I can do anything and there’s so much I want to do and… there’s the headframe, a reminder jutting out on the horizon, as I speed through a yellow-light at the uptown Reddi-Mart. “Shit, I have to get up at 6 for work tomorrow.”

I’m stuck on light duty, sweeping and mopping the dries—where the miners, timbermen, millwrights change out of their coveralls and shower at the end of the day. I sneak out for a pinner joint and hide away in a janitor’s closet on the ground-floor of the headframe, surrounded by Javex jugs and paper towel and the industrial-orange smell of heavy-duty hand cleaner, and I’m absorbed by George Orwell’s 1984, feeling like I’m the only one who’s been granted access to these secret workings of the universe. A mouse scurries in under the door and halfway up my boot. I look at it; it stares at me in shock—and bolts.

* * *

Rolling to site at midnight, listening to Russian radio on the CBC, most of my friends having returned south for school. I park the truck, take in a deep cool October breath, and sigh. I step into the arsenic plant, near the headframe, for a 14-hour shift.

* * *

I pull off my respirator and walk outside, to take a break from work at sunrise and watch as the world comes back to life around me. Clouds come in off the bay—the ones closest to the ground are lit up a bright neon pink and zip by overhead, the shades of pink and the speeds diminish in intensity the higher the clouds are. It’s hypnotic. In minutes, it’s over. I’m alone at work and shared the moment with no one.

* * *

You come in off the East Arm, or the North Arm, and begin to think, well, we must be getting close to home. You scour the horizon. Is that it? Yes, barely visible, but there it is, the tallest building in the territory. And then immediately, at that sight, your mindset, your language, even your posture changes—you leave the now of then behind, and drift back to the responsibilities awaiting you in town.