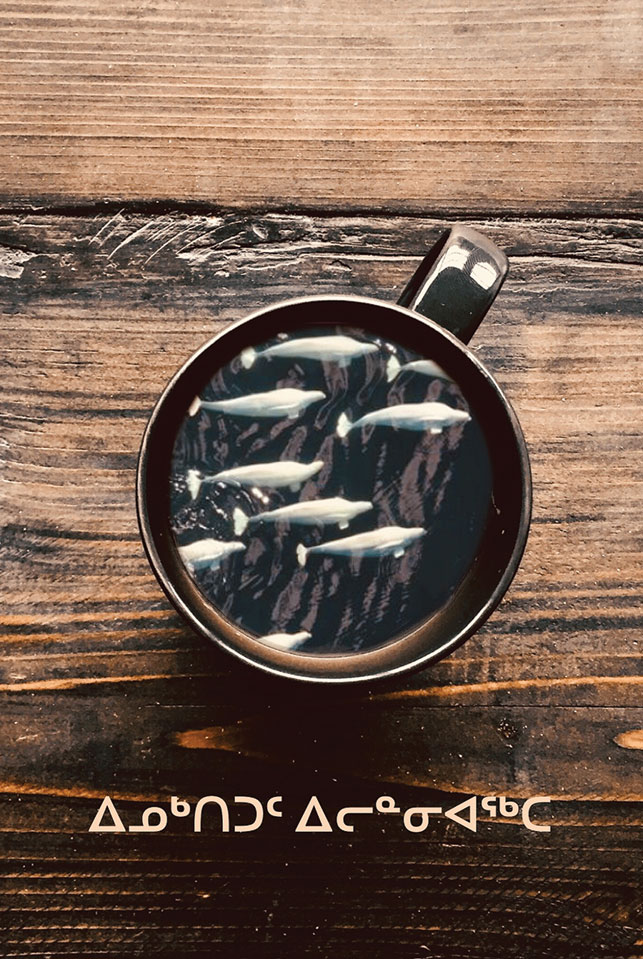

A teenage girl in Iqaluit stops in to visit her grandmother after school. She drops her backpack on the floor and watches as her grandmother pulls out her sewing bag and continues with her latest project—a pair of sealskin kamiit. The young girl has so many questions. Where did her grandmother learn the boot pattern? How does she make each stitch waterproof?

But she doesn’t speak enough Inuktut to ask her unilingual grandmother. They are together, yet isolated—the language barrier creates a wall too high for either of them to scale.

This is the reality for many Inuit families. Children, who go through the school system learning English as their primary language, don’t speak the same language as their grandparents. And with each passing year, this scene is being played out in more and more homes.

“When a person is unable to communicate with a grandparent, it puts a big burden on their heart,” says Aluki Kotierk, who has used her platform as president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the territory’s birthright organization, to fight for Inuktut—the umbrella term for all Inuit languages. “I think that has a big impact on someone’s self-identity as well, because when people are unable to communicate with their grandparents, they question whether they are Inuk enough.”

She has watched her own children struggle with this. Like many families, Kotierk can speak Inuktut but her children can’t. Several years ago, one of her daughters was angry and frustrated that Kotierk hadn’t taught her enough Inuktut to carry on a fluent conversation. But Kotierk was attending university in Ontario when her daughter was young. She was trying to be a good student and a good mother and trying to make ends meet. “I was doing the best I could. We are all products of our environment and our circumstances,” she says. Still, Kotierk wrestles with the feeling that she failed her daughter—a feeling she now channels into championing Inuktut to ensure it’s visible in every aspect of life in Nunavut.

A people’s history is encoded in its language, with rich stories behind the meanings and origins of words. A language articulates a unique outlook on the world, shared by all its speakers. The danger of losing Inuktut is real. According to Kotierk, Inuktut as the primary language spoken at home is declining at one per cent per year in Canada. By those estimates, the language will be lost within the next 34 years without drastic action. By then, only four per cent of households in Nunavut will speak Inuktut.

Kotierk sees Inuktut being given short shrift all the time. “Inuit are so welcoming that if we go into a meeting and there is one person who cannot speak Inuktut—even though we can all speak Inuktut—we’re all going to speak English,” she says. If the language is going to survive, she thinks some tough love is in order in Nunavut. “Everywhere we go we should be able to speak Inuktut.”

A territory where everyone can speak, read and write Inuktut has always been part of the vision for Nunavut, which divided from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999. So far, nothing has come close to stopping the decline, let alone boosting the number of fluent speakers.

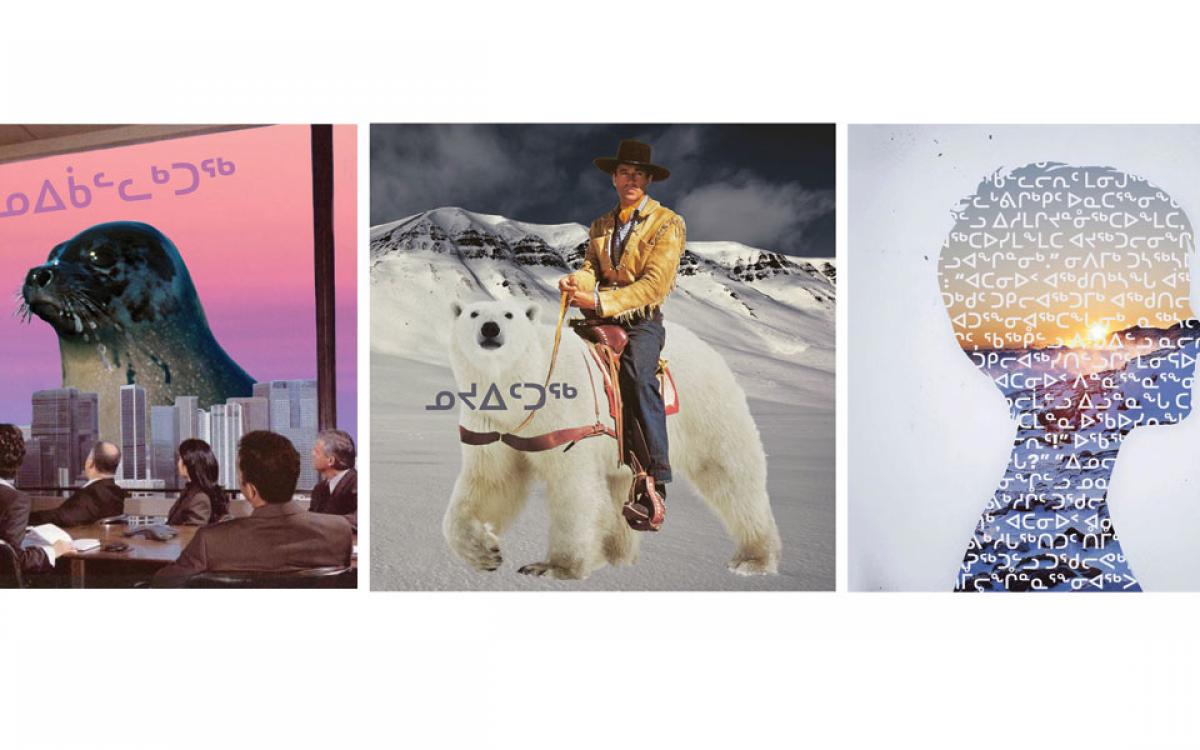

But Inuit are developing a standardized writing system that aims to do just that.

Since 2012, the Atausiq Inuktut Titirausiq Task Group, made up of language specialists from across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Nunavut, Nunavik and Nunatsiavut) is attempting to unify a language with a multitude of dialects and sub-dialects, written with nine different systems across an area that covers 40 per cent of Canada’s landmass.

A standard written language, the thinking goes, will bring consistent grammar, spelling and terminology to government documents and educational materials. It’s hoped that consistency will allow teachers to share resources and students to learn more quickly, bolstering literacy rates and creating the conditions for Inuktut to flourish.

“We’re trying to get more in line with easier communications with other Inuit, not just within Canada, but also in Alaska and Greenland as well,” -Jeela Palluq-Cloutier

Embedding language into the education system has worked exceptionally well in other countries, notably in Greenland and Wales, which undertook major revitalization projects to save their threatened languages. In 2016, Jeela Palluq-Cloutier, executive director of Inuit Uqausinginnik Taiguusiliuqtiit, Nunavut’s Inuit Language Authority, and members of the task group travelled to Wales. English rulers had driven the Welsh language out over centuries, but today it is the co-official language of Wales (along with English) and there are more than 475 primary, middle and high schools that have curricula delivered entirely in Welsh. “They get into the schools in the fall—August, September—and they’re fluent by March,” Palluq-Cloutier says. “So there was a lot of hope.” The language authority, an arms-length branch of the territorial government, has the power to direct departments to adopt standard terminology and orthography.

But the job of unifying Inuktut will not be an easy one. The task group, formed and funded by national Inuit organization Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, hopes to have a draft document ready this month on how to move forward with a written standard. If they are successful, it will be the largest Indigenous language revitalization project in Canadian history.

The first question the Atausiq Inuktut Titirausiq Task Group had to ask was where to start.

Even smaller areas of Inuit Nunangat, like the Inuvialuit Settlement Area, are home to many distinctive dialects, each one linked to specific geographical areas. Sallirmiutun is spoken along the coast in Tuktoyaktuk, Paulatuk and Sachs Harbour, as well as in Inuvik. Uummarmiutun, which traces its roots back to Inupiaq in Alaska, is spoken in Aklavik and Inuvik, while people in Ulukhaktok speak Kangiryuarmiutun, a dialect of Inuinnaqtun. Beverly Siliuyaq Amos, a task force member from the Inuvialuit region, says though each of the aforementioned dialects technically falls under the term Inuvialuktun, some words don’t translate between them. (Just take the word for scissors: It’s “kiputik” in Sallirmiutun, “hallihik” in Uummarmiutun and “kivyautik” in Kangiryuarmiutun.)

One improvement Amos would like to see is assigning a symbol to the letter “r” in Inuktut, indicating it’s pronounced like the throaty, guttural “r” in French. (Today, the community of Arviat, Nunavut, is a constant victim of mispronunciation.) This is just one of the countless considerations in front of the group. Despite the headaches and heated debates that come with combining Inuktut’s myriad dialects, Amos believes change is good if it strengthens the language.

But not everyone is ready to embrace standardization. One of the biggest sticking points, especially for elders, is what will happen to syllabics.

In 1840, Reverend James Evans, a Methodist minister and linguist, created the syllabic writing system to teach the Cree to read the bible. Later, missionaries brought the system, made up of symbols representing consonant and vowel combinations, to Nunavut. For older generations of Inuit, the syllabic system is special. It is the first alphabet they learned and the system still holds a strong religious significance to them. But syllabics were never adapted to Inuinnaqtun, used in the western part of Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region (Qitirmiut in Inuktut), nor do they exist in Nunatsiavut, Alaska or Greenland. To achieve a language that will be as widely understood as possible, the new system will use the alphabet more familiar to the rest of the country, Roman orthography.

“We’re trying to get more in line with easier communications with other Inuit, not just within Canada, but also in Alaska and Greenland as well,” Palluq-Cloutier says.

Not including syllabics in the official writing system doesn’t mean they will be lost though, says Palluq-Clouiter. “This is for the purpose of educational materials and government communication, but everybody who still uses syllabics will continue to use that,” she says. “Syllabics are not being abolished.”

Ian Martin, a York University linguist who has studied Inuktut and Nunavut’s education system for more than 20 years, says there are other languages written with more than one alphabet simultaneously. Serbian, for instance, can be written in either the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet or the Latin alphabet. “The two co-exist and they’re taught in the schools—all the children know both,” Martin says.

Many Nunavummiut are also concerned about losing their dialects if their words and spellings aren’t included in the new writing system. The task group hasn’t chosen one dialect. Instead, they’re trying to represent as many as possible. Still, the process is an exercise in compromise. For example, in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, people have always used the letter “y” to symbolize a “y” sound. But the new system will employ a “j” to symbolize a “y” sound to accommodate other dialects. However, Inuvialuktun speakers will see familiar letter combinations, such as “ts” to represent a “ch” sound, in the unified system.

Trade-offs must be made to come up with a standard Inuktut orthography that works for everyone and community consultations are vital to achieve that end. But the financial burden of travelling in the North means the group can’t go to every community to explain their work. So they’ve used local media, such as radio call-in shows and television, when they can’t get to a town to get feedback. “Education is key,” says Palluq-Cloutier. “We have found that there are a lot of people resistant to supporting a new writing system, but once they learn why we are doing this, most people come out supporting it.”

From the very beginning, Nunavut was intended to be a territory for Inuit, so why has the Inuit language fallen so far behind?

In 1984, when Nunavut was still 15 years away, then-Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development commissioned a report titled The Cost of Implementing Inuktitut as an Official Language in Nunavut. It provided comprehensive estimates of staffing and costs associated with ensuring Canada’s newest territory could deliver government and public services in Inuktut. But the report was ignored.

As a bilingual education expert, Martin authored a study on language instruction in Nunavut and found that the year before Nunavut was created, the federal government shelved discussions about Inuktut with the promise that it would look at Inuit language funding at a later date. When Nunavut was born in 1999, Inuktut was again pushed aside as the territory worked out the kinks of setting up a new government, Martin says. “The most efficient way would have been to do everything in English and, in a way, that’s kind of what happened,” he says. Inuktut, essentially, got buried under the immediate demands to set up a modern government.

If the federal government had dedicated adequate funds toward Inuktut during Nunavut’s infancy, the persistent drop in language use could have been avoided, Martin believes. In fact, it took until 2008 for the territory to pass an Official Languages Act, which solidified Inuktut’s place alongside English and French.

But even though there are scores more mother-tongue Inuktut speakers in Nunavut than French speakers (22,600 and 595 respectively, according to the 2016 Census), the federal government budgets similar amounts to provide services in both languages. Under the latest four-year Canada-Nunavut funding agreement, Inuktut would receive $15.8 million while French language services would get $14.2 million. Broken down per person, the funding works out to an incredibly disproportionate $175 per year for each Inuktut speaker and $5,970 for each French speaker.

Inuktut funding is used to develop language resources for schools and language upgrading programs, along with public servant language assessment and training and community-based language programming. French language funding pays for what the territory spends providing French services, such as translating government acts and regulations and providing court and health services.

Kotierk believes federal funding should recognize Inuktut as the majority language in Nunavut with both French and English as minority languages—and fund them accordingly. “Then the territorial government could rightly focus their resources on Inuktut,” she says.

And at least in the beginning, those resources should be focused on education in schools. Study after study has shown the positive benefits of students being taught in their mother-tongue first. For instance, they are more likely to successfully adopt not only second languages, but multiple languages, afterwards.

The message has always been clear: teach them young and teach them now. And this is where Nunavut takes the blame, Martin says. The Nunavut Education Act, passed in 2008, replaced legislation carried over from the Northwest Territories. One of its main goals was to have bilingual English-Inuktut education available to all students in Kindergarten to Grade 12 by 2019-2020. That target won’t be met. Not even close. A 2016 report found that of 27 schools surveyed, only 11 were able to follow the bilingual education requirements for Kindergarten to Grade 3. And just one school, Kugaardjuk Ilihakvik in Kugaaruk, was able to offer bilingual education up to Grade 5.

The problem is a lack of Inuit teachers. There were 597 teaching positions in Nunavut schools in January 2016, but only 201 Inuit teachers. The territory needs at least an estimated 230 more teachers proficient in Inuktut to be able to meet its requirements. Yet the Department of Education still doesn’t have a finalized Inuit Employment Plan—a requirement of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. This requires government agencies to have plans in place “to increase and maintain the employment of Inuit at a representative level.” In short, Inuit make up 85 percent of Nunavut’s population so they should make up 85 percent of the workforce.

Last year, Martin authored another report, this time condemning the Department of Education’s lack of a detailed plan to recruit and keep Inuit teachers. The Nunavut Teacher Education Program graduates 12 teachers per year, but the department only retains an average of nine, the report states. At that rate, and taking into account the retirement age of today’s teachers, the department wouldn’t have enough teachers to teach Inuktut from Kindergarten to Grade 12 until 2071.

“At the current rate of attrition of Nunavut teachers, the last Inuit teacher would be going out the door and turning out the lights in 2026 because there is no appreciable recruitment plan for Inuktut-speaking teachers,” Martin says. “I think really here the government is, yes, wholly to blame for not supporting the Inuit language through the education system. I don’t let them off the hook at all for that.”

But there are reasons to be optimistic—at least cautiously. In 2017, Paul Quassa, who was then minister of education and later Nunavut’s premier (he was ousted in a vote of non-confidence on June 14), proposed a controversial bill that would change Nunavut’s Education Act. Bill 37 suggested adding ten years to the deadline for Inuktut instruction in grades 4 to 9 and indefinitely postponing the deadline for grades 10 to 12. Nunavummiut, with Kotierk taking a leading role, protested the changes, deploring the idea of further weakening Inuktut. The bill was rejected thanks to good old fashioned letter writing and a social media campaign using the hashtag #killbill.

While premier, Quassa announced his government would aim to achieve a workforce that is fully bilingual in English and Inuktut within four years. (That on its own would be a monumental task. But when I asked the premier’s office how they expected to achieve this, I received no response. Several requests to speak with David Joanasie, Nunavut’s education minister, for this story also went unanswered.) And more money could be on the way to bolster Inuktut, including millions from a settlement agreement between the federal government and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., based on Canada’s failure to fully implement the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.

Martin says the stepping stones toward a bilingual Nunavut have already been set. Now it’s just a matter of following the path.

That path forward, like the decision to move ahead with a standardized written Inuktut, won’t be without controversy. What happens to dialectal diversity in 20 years if localized words and phrases aren’t part of the unified writing system? And how will Inuktut retake its place as the working language of the territory when so much of the world runs in English?

Questions like these will spur on some tough conversations. But a difficult conversation is infinitely more desirable than an impossible one.

Just ask a granddaughter whose questions about kamiit might never be answered.

This story has been updated since it ran in print to include the removal of Paul Quassa as Premier of Nunavut.