If you ignored the face masks for a moment, you could stroll through any of the larger communities in the North and almost imagine that the COVID-19 pandemic hadn’t really happened. People would give you a wider berth as you passed on the sidewalk, and you might notice a stronger sense of “buy local” among the shoppers in the stores you visit. But people would be out and about. The streets would be busy, much as they were before the pandemic. Almost.

Indeed, a superficial scan of the data suggests that the territories are coming through one of their most challenging years in decades beaten, but not broken. Nunavut and the Yukon both recorded positive, albeit weak, GDP growth in 2020—1.8 per cent and 2.9 per cent respectively, according to Conference Board of Canada projections—but they were the only two jurisdictions in Canada to do so. The NWT suffered more, seeing economic growth contract 7.6 per cent according to the conference board. But the loss is tempered by expectations for a return to modest growth this year. (The Yukon and Nunavut are expected to boom.)

Job markets turned in weak performances, too, with unemployment rates increasing across the board (up 1.6 per cent in the Yukon, 0.2 per cent in the NWT, and 0.6 per cent in Nunavut). Still, these were the lowest in Canada, and Yukon again posted the lowest unemployment rate in the country, at 5.2 per cent, substantially thanks to solid growth in its mining sector.

None of this data is positive, to be sure. But it suggests the North fared better through 2020 than much of the rest of the country. Here’s the problem: You don’t have to scratch hard to find serious economic troubles roiling just below the surface.

Consider the impact of COVID-19 on tourism. Travel restrictions and closed borders brought the sector to a standstill last year. In the words of Neil Hartling, president of the Tourism Association of the Yukon, operators were “swimming with one nostril above the water.” Donna Lee Demarke, chief executive at NWT Tourism, offers a less colourful but equally blunt assessment. “There’s so much that we don’t know… There’s no plan yet from all levels of government.”

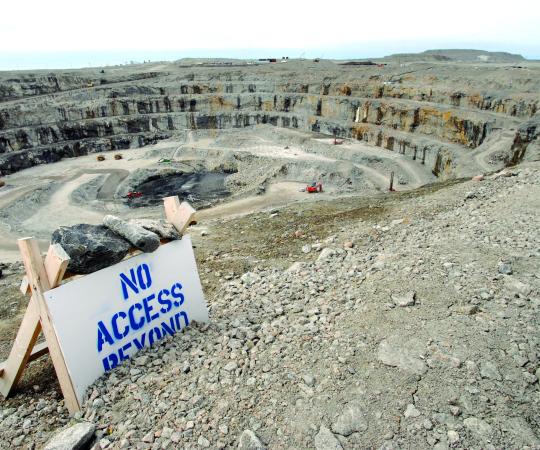

The bad news doesn't stop there. The mining sector, for example, is seeing some unwelcome trends, despite a glowing year for gold. According to Natural Resources Canada estimates, exploration spending and project appraisal spending was down in all three territories in 2020—six per cent in Nunavut, 20 per cent in the NWT and 30 per cent in the Yukon.

Meanwhile, in a budget tabled as this issue of Up Here Business was going to press—the first among the territories—the NWT government said it expected tax revenue to fall by $40 million due to the impact of the pandemic.

The data points and observations above are only a small grab sample of the issues the North will be confronting in 2021 and likely beyond. But one thing to bear in mind is that not all of the issues are pandemic related. Consider: A few weeks after he was named president of the Yukon Chamber of Commerce in November, Patrick Rouble surveyed some of its members, asking what kept them awake at night. “The pandemic was obviously an immediate and pressing issue in the responses,” Rouble says. “But the bigger issue was, ‘is my business model going to be sustainable in the future?’ There are so many changes.”

Indeed, the issues at the core of the northern economy—from technology to infrastructure to demographics—were there before the pandemic struck. Perhaps more than anything, COVID-19 served to exacerbate the concerns and questions, amplifying an underlying sense of uncertainty. If that's the case, the challenge for the North becomes: How do we get some of that confidence back?

The issue of certainty usually centres on mining and regulatory regimes across the North. No surprise there, given that the sector is the single-most important source of private investment in the territories. And again, at the surface level, mining had a positive impact on northern economies during 2020, especially in the Yukon and Nunavut. Highlights included Victoria Gold Corp. reaching commercial production at its Eagle project in July and the revival of production in the historic Keno Hill district with Alexco Resource Corp.’s Bellekeno project. The last weeks of 2019 also saw the resumption of operations at the Pembridge Resources PLC’s Minto mine and the achievement of commercial production at Angico Eagle Mines Ltd.’s Amaruq project.

But for all the upside and the sector’s resilience through the pandemic—the suspension of production at the Ekati diamond mine notwithstanding—2020 pointed to challenges ahead. Some of the decline in exploration spending was no doubt tied to decisions on the part of junior miners to delay summer field work made in the early months of the pandemic. Spending discipline was also the watch word for producers as they wrestled with emergency expenses such as chartering flights to bring staff to sites and paying workers from vulnerable northern communities to stay home. That's all easy enough to understand as a response to circumstances. But there is cause for greater concern, notes Ken Armstrong, president of the NWT and Nunavut Chamber of Mines. “The drop [in exploration and appraisal spending] is worrisome when compared to southern Canada,” he said in a November comment to the northern media. “Despite the pandemic-related restrictions and program delays, exploration spending [there] increased.”

Exacerbating that trend were news stories that raised concerns about the certainty of the regulatory systems, starting with the protracted Nunavut Impact Review Board hearings on Baffinland Iron Mines Ltd.'s proposal to double production at its Mary River mine and bring the project to profitability.

In the Yukon, meanwhile, the territorial government rejected a proposal in December from ATAC Resources Ltd. to build a 65-kilometre access road to a promising deposit at its Rackla gold project, citing opposition from the Na-cho Nyak Dun First Nation. The rejection of the proposal, which had been recommended for approval by the Yukon Environment and Socio-Economic Assessment Board, shocked industry representatives. “The message that the Yukon government is sending… is that the Yukon is closed for business,” said Ed Peart, president of the Yukon Chamber of Mines. “Yukon Government decided to throw out years of this work.” A few weeks later, it was the Yukon government's turn to complain about troubling signals as the federal government refused to greenlight BMC Minerals’ Kudz Ze Kayah project, which had received a positive screening report from the environment and socio-economic board.

If frustration is palpable in the mining sector, it is no less so among small- and medium-size businesses, with government procurement and regulation emerging as a major issue over the past year. In Nunavut, it surfaced in September as a sole-sourced contract to build a bridge in Coral Harbour went to a southern contractor over a local firm. Nunavut government policy gives special credits to resident and Inuit-owned business when bidding on contacts. Municipalities, however, are exempted from the policy, leading to questions about how projects are awarded.

In the NWT, the issue boiled over in July as the Tlicho First Nation called out the territorial government’s public tender to reconstruct an access road to Behchoko, the First Nation’s largest community. Grand Chief George Mackenzie called the tender a show of “complete disrespect” on the government’s part and said it should have offered a direct negotiated contract to the Tlicho in the first place. A few days later, the NWT government quietly cancelled a request for proposals for upgrades to the North Arm Territorial Park, which is near Behchoko. Following further issues raised by the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, Finance Minister Caroline Wawzonek promised a review of government procurement policies, including Indigenous procurement. A formal committee was established early in the new year and will submit its report in the spring.

When Patrick Rouble talks about uncertainty in the Yukon business community, he takes a broad view. Online shopping has been putting pressure on northern retail for years now. Newer trends, such as the greater acceptance of remote work that’s emerged under COVID-19, has the potential to accelerate change in the market for commercial real estate. A return to a more robust economy after COVID-19, raises further concerns about labour shortages.

Such issues are readily recognizable across the North. And the question remains: How do we rebuild certainty—or at least a greater degree of confidence? The immediate issue is pandemic recovery. The federal government, through Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency had spent more than $24.5 million by October of last year on support through the Northern Business Relief Fund, which helped businesses with costs such as rents, mortgages, utilities and insurance. More aid came through territorial governments, such as Nunavut’s support for Canadian North and Calm Air, the territory’s main airlines.

But with vaccination programs stumbling across the country, it will still be many months before the economy shows signs of a sustainable recovery. This is especially true for the battered tourism sector, which has already lost its 2021 winter aurora season due to travel restrictions and, even if borders re-open, is still likely to be operating with lean bookings through the summer. “Operators are still selling, with the caution that they may need to put over to 2022,” says Kevin Kelly, chief executive of Nunavut Tourism. “We’re all in that holding pattern.” So, ongoing support, such as the extension of the Northern Business Relief Fund to end of this fiscal year, will be required to ensure businesses that have survived the pandemic so far make it to the finish line.

In the middle term, territorial governments need to show greater commitment for the private sector, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. The Yukon has a head start with its new procurement policy; the test will be in its implementation and its broader acceptance. The NWT's procurement review, meanwhile, is being met with cautious optimism. “We’re somewhat hopeful this will not be another study that tells us exactly what we already know and gets put on the shelf,” says Renée Comeau, executive director of the NWT Chamber of Commerce. “At the end of the day, we have to create a competitive atmosphere that is attractive to the private sector.” (Part of that process, Comeau adds, is a reduction in the red tape that now hampers investment, from creating barriers for potential manufacturing to acquiring liquor licences for remote fishing lodges.)

The big picture, however, rests on the ability to address outstanding issues around infrastructure. In the Yukon, a growing mining sector will put pressure on its power generating capacity. Road systems and hydro grids are vital to the NWT. Nunavut needs ports and general connectivity. The best way to build certainty based on these needs is a strong sign from the federal government. The ball is in their court.