There’s something about carvers that makes them seem more Thor-like than human—maybe it’s the heft of the stone they work with, or the temperament required to coax form from unyielding elemental materials with a hammer and chisel.

Given the scale of their artistic output, brothers David Ruben Piqtoukun and Abraham Anghik Ruben may very well be hybrid creatures—part god and part man.

There is a particular piece of Abraham’s, a career highlight, which exemplifies his creative powers. Memories: An Ancient Past is made with an enormous ossified bowhead whale skull that Abraham’s nephew found 30 miles up the coast from Paulatuk, NWT—a community of about 300 in the Beaufort Delta and the Ruben brothers’ birthplace.

By Abraham’s estimation, the bone is several hundred years old. Over decades, weather and waves acted upon the skull’s surface, giving it the perfect, porous consistency for detailed carving. In 2010, Abraham travelled back to Paulatuk, where he arranged to have the skull shipped to Inuvik, then to Vancouver, then to Salt Spring Island, B.C., where he has lived and worked since 1986.

“When I first met the bone, when we offloaded it and opened the crate, I saw the shapes and forms. I was very emotional, it was phenomenal,” Abraham tells me over the phone. “The material has its own memory, and I saw an opportunity to make a piece telling the legends, life, and beliefs of the people.” His epic sculpture articulates the tenets of the Inuvialuit story: mother and child, hunter, Shaman, spirit world.

Think about the story of that enormous whale: its life, spent bashing through thick sea ice, and its death—possibly, according to Abraham, at the hand of whalers that came all the way to the Paulatuk region from San Francisco. Then, its 200-year rest on that gravelly shore, and its long posthumous journey—first pulled across the tundra by Abraham’s nephew’s snowmachines, then hoisted into a shipping container, arriving in the studio of a famous carver thousands of miles away, and later travelling on to galleries across the country. The piece is for sale now, for a price of $2 million.

Not every artist would embrace the task of carving such a massive object. (The skull is more than 800 pounds and almost seven feet wide). But “there’s a creative factor that runs deep, deep in the family, from one generation to another,” says David. “We are artists and so [we] get to interpret life differently and in exciting ways.”

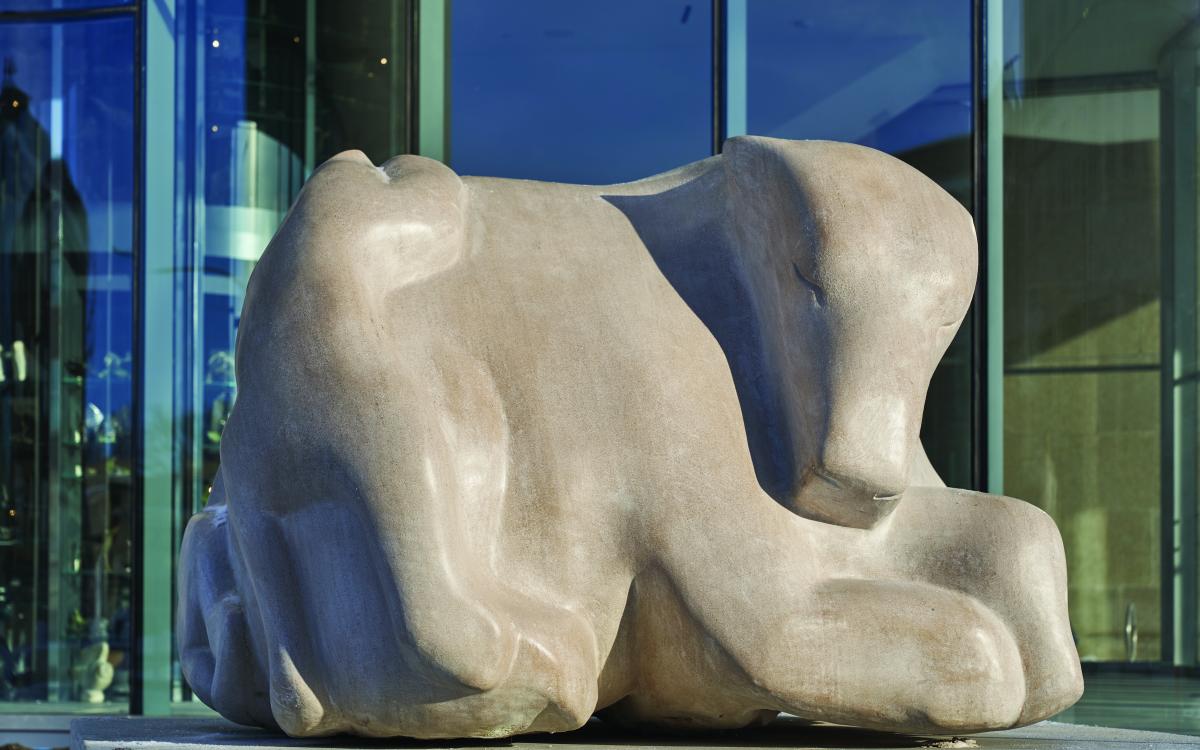

Abraham, born in 1951, was inducted into the Order of Canada in 2016, and was the first Inuk sculptor to have a solo show at the illustrious Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., in 2012. His new large-scale polar bear sculpture, Time to Play, made from a five-tonne piece of limestone, now graces the plaza of Quamajuq, the Inuit Art Centre in Winnipeg.

David, a year older than Abraham, won a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in March 2022. It’s the highest possible honour to bestow upon an artist in this country. He was also one of the first Inuk artists to have a solo art exhibition, Between Two Worlds, for the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1996. In 1989, he was appointed to UNESCO’s Canadian Committee for the World Decade

of Cultural Development.

I manage to reach David while he’s driving down Highway 401 in southern Ontario with his wife Katherine. They put me on speaker phone and David shouts: “We were just lost for three hours in Toronto, my wife telling me to turn this way, turn that way, until finally I said shut your face!” They both erupt in laughter. He is kidding, of course. “It’s our anniversary today. Married 24 years. To the same person, eh? So, I can joke like that.”

The couple are on their way to Plainfield, Ontario, where they’ve lived for several years. David speaks proudly of the strong creative gene in his family. “There are a lot of Rubens: 17 in our immediate family. Enough for a football team.” His mom, Bertha Thrasher Ruben, sewed clothes and footwear for the entire family. His dad, Billy, is an artist too. “My dad was a carver, yes. As a youngster I watched his attitude towards pre-cutting and rough-shaping, then

the detailing.”

Attitude, it turns out, is very important to the carver’s process. Over the years, David has given many interviews about the spiritual, shamanistic nature of his work. (His great-grandparents, Apakark and Kagun, were Shamans.) Yet he speaks freely about the fallible side of carving too.

When he was still new to carving, he tells me, the walls of his garage-studio became pocked with dents and holes. He’d get angry and throw chunks of stone, “because the stone would fall apart like a cheap suitcase.” As he matured in his art, he learned to carve with the right touch, to study the material first, to have a discussion with it. “I’d roll it around from different angles until something emerged, ‘til an arm or a finger or something inside the stone started tickling my nose.”

Abraham was the first brother to take to carving, studying at the Native Arts Centre at the University of Alaska in the early 1970s. Art school allowed him to reconnect with his culture and his past. After, he moved to Yellowknife, his “staging ground” as he put it, a place to test his mettle as a new artist.

He had a lot to prove to himself, and a lot of memories to work through. Both brothers were taken from their homes as boys and forced to attend residential school—David when he was five and Abraham when he was eight. Until then, the boys lived with their family on the land. They were a small nomadic group, migrating along the Arctic coastline, using traditional skills to live. David loved roaming in the rugged beauty, wearing whatever hand-sewn clothes fit—a barefoot, snotty-nosed, happy kid.

“My parents and relatives gave me a spiritual understanding of where I stood with the rest of the world,” Abraham explains. “They taught me I have a soul, that animals have souls. Even as a young child I knew who I was. But that point of view was beaten out of me in school. It wasn’t until 18, 19 years old, that I learned to take back my voice.”

Abraham’s early carvings were intensely personal. Wrestling With My Demons depicts a red-eyed demon clutching the head of a figure with a bottle-shaped torso. “This sculpture is a personal interpretation of my life,” Abraham notes, in his artist statement. “It is a mirror of my past, a signpost for the present, a reminder of yet unresolved issues and day-to-day struggles. Past struggles include twenty years of alcoholism and my recovery, and years in the residential school system. These demons still make themselves known, but as time goes by, they have become faint echoes and whispers.”

While Abraham was in art school, David moved around the country trying every job he could. But he kept getting fired. “I lived everywhere, I even lived on the moon for a while,” he jokes. “I reflect on my nature a lot, and I had to get tough at a really young age as I had difficult times with the nuns and authorities. I often fought back, even at five years old, but I’d get beaten and get my ears pulled.”

When Abraham showed David how to carve, he found a way to be his own boss. As Abraham remembers it, the moment David learned he could get paid for making art, he asked ‘Can I borrow your phone?’ David called his boss in the oil fields and quit, right then and there.

Through carving, David also found an outlet for his pent-up energy, a way to work through past trauma, and a way to explore both the world and his own mind. “I still recall it like it was yesterday,” he says. “My brother gave me instructions, some tools like files and rasps and sandpapers, and said the rest is on your own. I thought, ‘This is really interesting.’” It took him four years to learn to carve decently, he says, “to be able to make objects that actually looked like something.”

There’s an old adage in the fitness world: pain is weakness leaving the body. In the craft world, the quip is reversed: physical pain or injury is what allows craft to enter the body, a necessary milestone toward acquiring deftness and skill. “The tools are clumsy and you have to grip everything,” says David. “It took a long time for my hands to get in shape, to get strong, to know what to do.”

When you look at David and Abraham’s carvings, it’s interesting to try to reconcile their spiritual and aesthetic power with images of the artists themselves. Who are these men? What characteristics must they possess that enable them to make such massive contributions to art and culture?

My favourite representation of David is a video made in 2016 by the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec. He looks youthful and a little cheeky in an aqua Hawaiian shirt and Puma ball cap. (I couldn’t help but notice the similarity of the Puma logo to the contours of Inuit sculpture—both have such spare yet animistic lines.)

David is speaking about his carving called Bear, Shamanic Transformation, which depicts a wide-eyed, fanged figure with his head canted to one side. He made the piece in order to draw strength from it, at a rough time in his life. In the video, David cants his head to the side, too. “Don’t mess with bear-man,” he says. “They’re able to fly through the ground, fly through the skies, fly through ice, fly through solid objects…”

David is a nervy and emotional carver, always trying new things. He’s been working with bronze casting, and has even made installations with metal, light, and water. His work is memory in visual form—encompassing both his own personal recollections as well as the collective memory of the Inuvialuit.

Abraham has a thoughtful appearance. There’s a photo of him taken by photographer Fran Hurcomb in 1977, during his hippie years in Yellowknife. It catches him talking, mid-sentence. He’s leaning forward, gesticulating, as though trying to explain something serious to his far-out friend.

His carvings are always intense, known for the expressive detailing of their knotwork and ornamentation, for how they rigorously interpret the connections between Inuit and Norse mythology. He’s fascinated too with the migration patterns of ancient peoples. Whale bone and soapstone, in Abraham’s hands, almost flow like liquid. A Viking boat traverses the ocean, the hair of Sedna the sea goddess undulates in the waves. He’s a master.

The most recent photo I can find of Abraham—on the internet anyway—was taken in 2020 at his outdoor studio. He looks thinner and a little older, still sporting his characteristic moustache. Again, the camera catches him gesturing, mid-sentence, eyes alight, likely talking about his in-process sculpture, Time to Play, which sits on scaffolding beside him. In the background, several other large, partly-completed sculptures sit waiting for his attention.

It’s an ordinary photo of an extraordinary man. Audiences get to see finished masterpieces, but don’t often get to learn the how, the why, or the psychological toil that goes into each piece—let alone the human inside the ‘famed artist.’

“It is one thing to tell an Inuit story, and another thing entirely to understand and believe in what you’re trying to do. I often used to ask, ‘’Am I bullshitting myself?’ And I don’t believe I am,” Abraham says. “There are too many of what I call these Dremel-tool craftsmen who just bypass the creative process to sell. But for me, I keep hitting the wall again and again until I figure out the creative process, until I find the soul of it.”

The brothers’ personal histories are complicated. Inuit art history is complicated too, involving the support of marketing initiatives in southern Canada—both a blessing and a curse, depending on how equitable that support turns out to be.

A Dremel—a rotary power tool—makes carving physically easier, though Abraham is really commenting on spiritual integrity. Southern markets may have helped to economically sustain many Inuit communities, though for certain exemplary artists, their work is a calling and not simply a job. It’s a burden and a joy.

In 1995, David made Airplane, a powerfully symbolic piece that is imbued with the “fighting back” spirit of that little five-year-old boy. It shows an aircraft hovering over an iglu, and a figure—himself—hovering over the plane. “I did not want to get on it,” David says of the plane that came to take him to residential school every fall. It is significant to him, and to the many people who have seen the piece, that as an artist he was able to place himself above it, in the position of overcomer.

“With the introduction of modern religion, the shaman has slowly disappeared,” he wrote a few years after making the sculpture. “But they live through the artist in this day and age. Myself and my brother, we are the extensions of that. We are just a tool for somebody else. Some of the sculptures that I create are so powerful—it’s as if they are emitting a life force.”

There is a toll to acting as spiritual conduit, though. Both brothers’ work has been lauded for how it ushers ancient stories and original imagery into our contemporary world, shaping audience imagination anew.

I get the sense, when talking with Abraham, that he feels drained from time to time. In the Marvel Comics version of Thor, the Norse hero sometimes grows weary of his cosmic calling. In Abraham’s case, he has to carry thousands of years’ worth of legends and stories.

And carving is just so physical. Since the outbreak of Covid-19, he says, he has switched to painting. He’s working on about 40 different canvasses, which will be part of a show at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 2024. The paintings are abstract and tell the story of what he calls the “Arctic Apocalypse,” both in terms of historical events and current climate conditions. The work is informed by the cubist work of Picasso and his contemporaries, as well as masks from traditional Alaskan peoples. “Well, it is a lot lighter!” he jokes, when asked how he found the transition from stone to brush. “Seriously though,” he adds, “I come back into the house after a painting session and my wife says I look wild-eyed and exuberant. As opposed to carving, where, apparently, I look tired out.”

A friend of mine now owns the house Abraham lived in during the 1970s, a cozy, two-story on Bryson Drive in the heart of Yellowknife’s Old Town neighbourhood. Walking by that house the other day, I imagined him sitting on that porch, carving or talking with friends—or pondering the significance of a dream.

“When I was in Yellowknife in ’76 or ’77, I had a dream,” Abraham says. “In the dream I met with an Elder. He took me for a walk in a gallery, overlooking the Don Valley in Toronto. He said to me, ‘In dreams all things are possible.’ It was a dream about my being an artist. The spiritual shock of what he said hit me like a sledgehammer. My knees buckled. That dream came true, literally, six months later, when I got an invitation to go to Toronto, to work with a gallery.”

“Making the art is one thing, knowing your place in this world is another.”