It is something one might expect to find in the countryside of the British Isles. Yet, roughly 60 kilometres upriver from Fort Smith, NWT, among the small cluster of Stony Islands, behind a screen of aspen, spruce, willow, and scrub, there exists the remains of a lime kiln.

With its curved, three-metre dry-stone wall, it’s an uncommon structure for the Slave River. The only record of it is based on notes from archaeologist Marc Stevenson’s conversation with a “Brother Seaurault” (possibly misspelled from Serrault). He states the kiln was “used by the residents of Fort Chipewyan in the 1910s and 1920s to make whitewash for their log homes.” If that’s accurate, the kiln has been there for a century.

The kiln is certainly showing the impacts of time, seasonal flooding, and ice scouring. When the site was documented in Stevenson’s 1980 archaeological survey along the Slave River, the stone wall was separating from the bedrock. This wall is now beginning to collapse away.

Whitewash, a by-product of quicklime production, was crucial for preserving building exteriors. First, quicklime was created at high temperatures through the controlled firing of limestone inside of a kiln. To make whitewash, the quicklime was mixed with water in a process called slaking. Applied like paint, whitewash created an impermeable surface, making exterior walls waterproof. It was also flexible enough to account for shifts in wood or rock structures due to changes of season. Whitewash has been used in construction as mortar in a putty form, too. (This practice dates back to the building of the pyramids.)

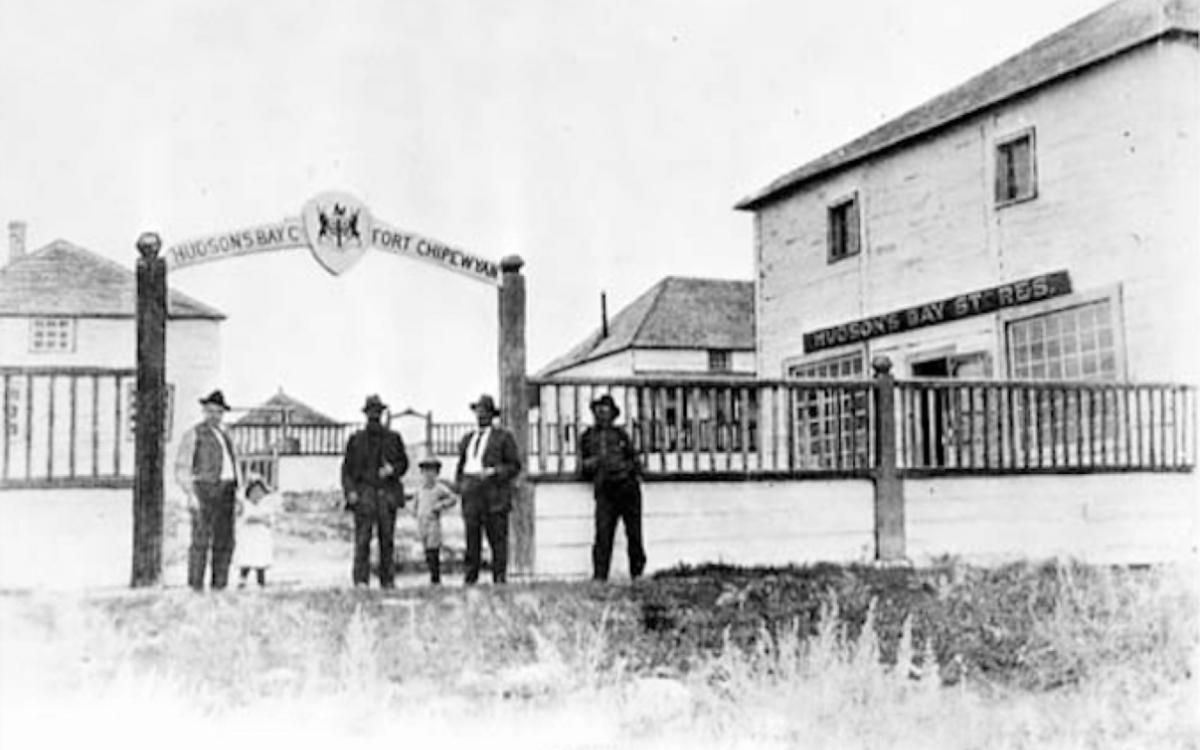

Stevenson’s records do not identify the specific “residents of Fort Chipewyan” who used the Stony Islands kiln, but we do know the Hudson’s Bay Company burned lime for use in the construction of its buildings. Historian Harold Innis, in his economic history of the Canadian fur trade, noted the HBC’s policy of reducing imports of provisions and supplies to lower its overhead expenses. Employees were expected to fish, hunt, and trap for themselves, as well as prepare and salt various game. They were also supposed to engage “in brewing, and in cutting and rafting down firewood and timber for repairs and building; and in gathering limestones for burning lime.”

As the HBC moved inland, many of these aforementioned provisions and supplies were acquired through trade with Indigenous residents. In time, with increasing settlement in the Slave River area, these same items became products in the emerging cash economy. A publication of the Department of Education of the Northwest Territories describes how residents of Fort Resolution manufactured lime. The booklet—entitled Getting Lime—is part of a series of translated and illustrated memories and legends told by elders. Antoine Beaulieu, translated by John Beaulieu, describes the lime-making process:

In the old days, people did different things to make a living. One way was to make lime for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

First an oven was made of flat rocks. These rocks were put along the bottom and sides of the oven. Then iron bars were placed across the top of the oven. When the oven was ready, flat lime rocks were placed on top of the iron bars and a fire was built in the oven. Spruce driftwood was used to make the fire as other woods made too many ashes. People would begin in the morning and keep the fire going all day and night. When the large lime rocks fell through the iron bars they were ready. Then the firewood was carefully taken out of the oven. When the oven was cool enough, a large canvas was put over it and left for three nights. Then the lime could be bagged.

The Hudson’s Bay Company paid six dollars for every bag of lime. The lime was used to insulate the log houses. Lime was mixed with wet sand and put in the cracks of the house. Also, lime was mixed with water and left to stand overnight. Then the mixture was used to whitewash the log houses. Whitewashing the houses helped to insulate them as the whitewash filled many of the smaller cracks.

Near Fort Resolution today you can still see the remains of the lime ovens. They are now broken-down and overgrown with bushes, but once they were very important.

It is quite likely that this Fort Resolution story belongs to the same time as the Stony Islands kiln. The early twentieth century saw an influx of outsiders enter the region. They quickly adapted to make a living—in hay camps, or as woodcutters or free-traders—supplying a variety of products to the growing communities along the Slave River.

We don’t know who operated the kiln on the Stony Islands, where rich local limestone was in abundance. It may have been the Hudson’s Bay Company, or independent business people, or Fort Chipewyan residents. Based on its design, it appears to have been made by someone familiar with kiln construction in the British Isles.

Whomever it was, they left behind a galvanized pail, a metal pry bar and a marvellously well-crafted dry-stone wall which still stands as a testament to the era of transition from the fur trade to an early cash economy.

Unfortunately, this living history is inevitably succumbing, like the wall itself, to the currents of the river and of time.