Hired out of Winnipeg in 1895, James Allen Rowand Balsillie was still in his teens when the Hudson’s Bay Company sent him north as an apprentice clerk. Six years later, he married and started a family while moving from post to post to learn the fur-trade business. By 1912, he had been sent to Fort Providence to oversee the fur-trading post. It was a perfect location for his growing family; the Catholic mission in the community had a school that taught up to Grade 5. By 1921, however, Balsillie’s oldest son, at age 14, had reached the end of what the mission school could offer.

Balsillie needed to take the boy south to Alberta to live with relatives in order to continue his education. So, after 26 years in the North without taking leave to go Outside, Balsillie asked for time off. The Hudson’s Bay Company granted him one week, not including travel time.

It would be easy to assume Balsillie’s first journey south in more than two decades would have left him marvelling at the social changes he missed, as if he’d slept through them. Society had been through the horrors of the First World War, experienced the widespread adoption of the motor car, and, in the midst of the Roaring ’20s, was watching traditional conservative social mores fall to the wayside.

But life in Balsillie’s corner of the North had been changing rapidly, too. And by the end of his trip, he would know which world suited him best.

Life in Fort Providence started taking on new momentum after the autumn of 1920, when Imperial Oil struck black gold at what is now Norman Wells. When word got out, many in the South wanted to cash in on the discovery.

The first indication 1921 was going to be an eventful year in Fort Providence was the arrival that spring of an airplane owned by Imperial Oil en route to Norman Wells. After buzzing a group of Dene travelling on the river ice, it made a low pass over the community and then landed in front of Balsillie’s house.

This was the first airplane to come to the NWT and its story became the stuff of legends. As Balsillie, a first-hand witness, would later recall, “[First Nations] thought that the machine was the devil, and immediately said that it had been their contention all along that the white man, when he joined up with the devil, could do anything.”

He would add, “There were fifty dogs around the post when that machine came into sight, and we didn’t see one of them for two days.”

What concerned, and perhaps frightened Balsillie, however, was what he saw a few weeks later, when the ice on the Mackenzie River broke. As one newspaper described it, “The amount of river craft on the Mackenzie announces a new era for the north in emphatic manner; before the first steamer reached Fort Providence, 92 vessels of different kinds passed downstream, including launches, scows, and canoes.”

The oil rush was on, and it would change the North forever.

What followed that early rush of smaller boats and made up the bulk of what Hudson’s Bay Company records referred to as “Norman Oil Fever” were the larger steam-driven paddlewheelers with passengers and supplies, motor-driven barges with heavy equipment, and sleek Imperial Oil gas-powered boats capable of then shocking speeds of 30 miles per hour.

The Hudson’s Bay Company’s paddlewheeler, the SS Mackenzie River, described as a “comfortable steamboat with cabins accommodating forty first-class passengers,” was the preferred mode of travel for newspaper reporters and magazine columnists coming to the NWT to witness and write about the incredible

oil rush.

The federal government saw the rush as an opportunity to check a few boxes on its to-do list, too. It sent famed land surveyor Guy Blanchet to produce accurate

maps. The government also sent a group to negotiate Treaty 11, which would extinguish all claims Indigenous people had to that far corner of Canada.

The government also had an opportunity to demonstrate, in a morbid manner, that the long arm of their law reached all the way to the territories. The July 19, 1921, headline in the Edmonton Bulletin read, “Indian Murder Trial at Fort Providence Impressed Natives With British Law: Tribes Brought in to Witness Trial Which Culminated in Sentence of Death.” The case was the first criminal trial in the NWT and involved a man named Albert Lebeau, a part-time employee of the Catholic mission in Fort Providence accused of killing his wife and baby. Balsillie was one of the jurors.

Southern reporters and photographers covering the trial found out that Balsillie, after 26 years in the North, had been granted a week of leave to take his son south to live with family and attend school. They also learned that Balsillie had arranged to travel to Edmonton with the returning judge and lawyers from Lebeau’s trial. Reporters were ordered to keep an eye out for his arrival and were eager to write about his Rip Van Winkle moments. The press was all over him when he got there, asking his impressions of southern politics, women’s fashions, and, of course, motor cars.

What they found out was that he didn’t know anything about politics and didn’t care who would win that year’s federal election. (It would be the Liberal Party under William Lyon Mackenzie King, serving his first term as prime minister.) On the question of women’s fashions, he said, “I guess these styles haven’t reach our part of the world yet.... These ladies these days don’t seem to burden themselves down with any too much superfluous clothing.”

Balsillie had a rather terse answer to the motor-car question. One reporter wrote, “It remained for an Edmonton taxi driver to give this pioneer his first joy ride,” but failed to report if the ride was either a joy or terrifying.

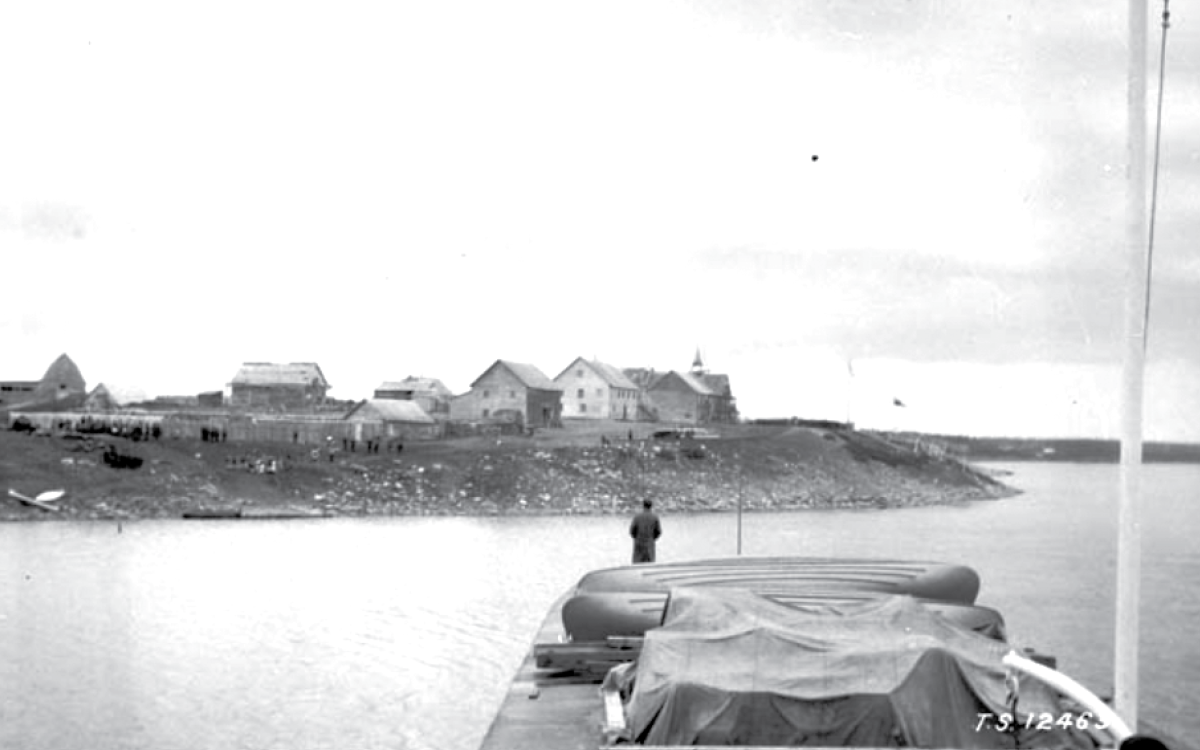

Balsillie’s week of fame was over all too quickly. He was due back in the NWT to take over as the post manager at Fort Resolution, a bustling community on the south shore of Great Slave Lake. And from the sounds of things, he had enough of city life well before his brief trip was up.

As the Bulletin reported, “A week’s leave in twenty-seven years, and before the last day comes pining to get back to his northern wilds—Jim’s friends… say that this is a record of delayed leave which would make the hardest used private in the late war meditate on his wrongs.”