In the summer of 2021, an interesting development occurred in the world of uranium mining. Prices for the metal began to climb after a decade-long slump. The growth curve that followed was steep, more like a vertical line. By this summer, prices were hovering close to US$50 a pound. That was still far below the previous peak north of US$75 per pound in 2011, but more than twice the price from the year before.

Several factors contributed to the rise, a long-awaited event among uranium miners and explorers. For starters, political turmoil in Kazakhstan, the world’s leading producer, has created uncertainty over the current supply. In the bigger picture, however, the World Nuclear Association credited a simple fact: Demand is rising due to global investment in nuclear power as a measure to combat climate change. And thanks to the price slump through the 2010s, mining companies have had little incentive to produce more uranium and close the gap.

How high will prices go? Who knows, but the most bullish analysts say they could peak at US$200 per pound before finally settling at US$100. Whether that’s true remains to be seen. But rising prices are stirring uranium mining and exploration firms from their soft-market slumber. Even in the North.

This year, two companies announced plans to resume uranium exploration in Nunavut. Forum Energy Metals Corp. hopes to begin work on its claims near the massive Kiggavik uranium deposit next year. ValOre Metals Corp., meanwhile, returned to its Angalik property this past spring with an $11-million drill program.

Both projects are in the Kivalliq region, west of Baker Lake, and both are years out from deciding whether mine development may be feasible. But they also raise a question: Nunavut has a challenging history with the prospect of uranium development dating back 40 years. The subject has always been controversial. But attitudes have also evolved. And Nunavut today is better equipped politically to deal with the issues and has more experience in working with the mining industry than ever before. Will that change the debate around the prospect of possibly backing a uranium development?

It’s far too soon to tell. No one has proposed building a mine, and it will be years, if ever, before someone does. But a look back at the uranium industry in the territory offers interesting clues about might play out in the not-too-distant future.

> The search for uranium first came to Nunavut in the early 1970s in an exploration boom that swept Canada’s mining districts alongside the rise of nuclear power. More than a dozen companies were active in the territory at that time, among them Urangesellschaft Canada Ltd. which would discover the Kiggavik deposit, about 80 kilometres west of Baker Lake. Despite its size—the resource was estimated at 133 million pounds—Kiggavik failed to attract much attention, overshadowed by higher-grade discoveries in the Athabasca Basin, which supports Saskatchewan’s uranium industry to this day.

But Kiggavik wouldn’t be totally ignored. In 1986, Urangesellschaft released a pre-feasibility study on developing a mine at the site. Although the move was met with swift and furious opposition in the North, the company continued to move forward, undaunted.

In 1989, it submitted a formal project plan to the federal government, which then controlled resource development in the North. The proposal poured more fuel on the fire of opposition in the North, and the debate grew even hotter. Central concerns included potential health risks, the safety of land, water, and wildlife, and the ethics over developing a resource that could be used as readily in nuclear weapons as in power plants. Adding to the tensions were widespread fears that governments quietly supported the proposal for the sake of economic development—and in sharp contrast to strong public opinion.

The debate climaxed in March 1990, when Baker Lake held a community plebiscite on whether to support or reject the mine. The vote came in overwhelmingly against Urangesellschaft. Three-quarters of Baker Lake’s eligible voters cast ballots in the plebiscite with 90 per cent opposed. Urangesellschaft saw the writing on the wall. With the federal government also taking an increasingly dim view of the mine proposal, the company packed up and went home. A short time later, it sold the property.

Eventually, Kiggavik ended up in the hands of Areva Resources Canada Ltd., which in 2006, renewed the prospect of developing a mine, but with an entirely different tone. Where Urangesellschaft had been accused of being heavy-handed and dismissive of community concerns, Areva started by opening a dialog with Nunavummiut. It established a community office in Baker Lake to provide information in both English and Inuktitut. It also created a regional relations committee with representation from each Kivalliq community.

Its more collaborative approach was met in kind. In 2007, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the organization that administers the Nunavut Land Claim, approved a formal policy outlining the conditions under which uranium projects would need to operate on Inuit-owned lands. (In a further show of openness—or conflict, depending on who you ask—NTI signed an agreement with another uranium exploration firm a year later. It marked a path for exploration and potential development in exchange for an equity position in the company.)

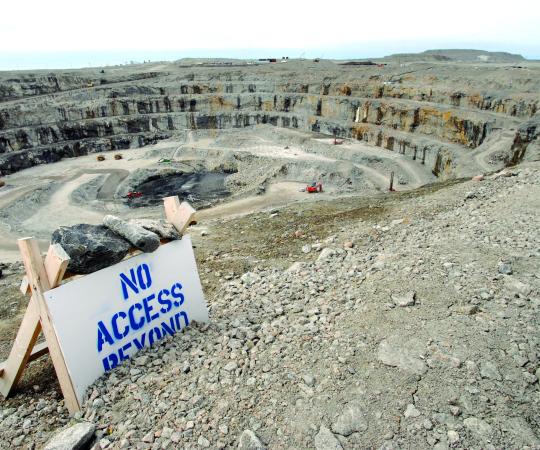

In 2010, Areva submitted a proposal to the Nunavut Impact Review Board to build a mine based on four open pits and one underground development that would, according to news reports, create between 400 and 600 jobs, generating $200 million in wages over 25 years. Despite the thaw in the tenor of the debate around uranium development, however, the proposal stirred intense opposition, focused again on health, safety, and environmental impacts.

The review board took five years to work through its process, during which time uranium prices entered their slump. Finally, in 2015, it rendered its decision. It could not recommend approval of the Areva plan, largely because the company, faced with prolonged weakness in the market, could not say when it would start development at Kiggavik. The idea of writing a blank cheque for a mining project with no timeline was too big an ask for the board. As it wrote in a press release announcing its decision, “The Kiggavik Project as presented has no definite start date or development schedule. The board found that this adversely affected the weight and confidence it could give to the assessment of future ecosystemic and socio-economic effects.”

A year later, the federal government accepted the review board’s decision and sealed the fate of Areva’s plan.

> If a company eventually files an application to develop a uranium mine in Nunavut, one thing is certain, at least for the foreseeable future: Any proposal will provoke serious debate. The stigma around the industry is not easy to shake, no matter how much supporters try to position nuclear power as part of the world’s solution to climate change. That said, the past decades of the uranium debate in Nunavut shows that attitudes in the territory have evolved. It is better equipped today, both politically and economically, to deal with the issue on its own terms.

Still, uranium is a challenging subject. In November 2020, for example, Nunavut MLA John Main told the territorial legislature that it may be time to review the government’s own uranium policy, which was released in 2012 and mirrors the NTI position. “I think we should consult Nunavummiut about whether they support uranium mining or not, and whether we should be talking about this matter… I’m disconcerted,” said Main, who also described himself as otherwise in favour of mineral development.

A year later, the government of Greenland passed an outright ban on uranium mining and shut down a promising rare earths project that also contained the mineral. It’s hard to say how developments in another country might affect decisions in Nunavut, but the Greenland example shows that strong opposition to the uranium industry remains close to the surface.

On the other hand, Nunavut is a more sophisticated territory when it comes to mining than it was in the 1980s or the first decade of the 2000s. The years following Areva’s application to the Nunavut Impact Review Board saw the opening of four new mines in rapid succession, creating an economy that has boomed by measures such as GDP growth. With the additional experience of having negotiated impact and benefit agreements with the development of northern diamond mines, land claim organizations are well experienced in setting the conditions and articulating the expectations required to earn their support.

How much that comes to bear on any future uranium proposal remains to be seen. And the exploration projects returning to Nunavut today have a long way to go before making any decisions that could lead to such a proposal, if they get there at all.

Given these realities, the only certainty going forward is that support or opposition will ultimately depend on the degree of certainty among Nunavummiut that their issues have been addressed by a proponent and that their voices have been heard and incorporated into the design and development of a project. On that point, perhaps the last word here should go to Kono Tattuinee, president of the Kivalliq Inuit Association.

“There are some people that may be starting to change their minds about uranium mining. And there are others whose minds haven’t changed,” Tattuinee wrote in an email to Up Here Business. “Ultimately, it will be up to the people in an affected community to decide if they would support uranium exploration or development.”