Thanks to the pandemic and Ukraine crisis, global energy markets have been bouncing around like they were riding in the back of a pickup on the old Alaska Highway. Natural gas prices in Europe hovered around 20 per megawatt-hour for most of the last decade. This March, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, they hit 345 per megawatt-hour.

You don’t need to be a chartered financial analyst to know that a price increase of 1,625 per cent will be good for your business case. So, Northerners are googling old reports of natural gas resources and blowing the dust off their globes. Could our gas land some of the money flowing out of those European wallets? After all, the Canada Energy Regulator thinks there are 16.4 trillion cubic feet of gas already discovered in just the NWT. Yes, that’s a “T” for trillion. And yes, that’s “already discovered.”

This isn’t the first time thoughts of exporting that gas have percolated across the North. In the 1970s, we had the Mackenzie Valley gas pipeline proposal. In the early 2000s, we had Mackenzie Valley 2.0. Outside of the North, liquefied natural gas (LNG) was all the rage in the 2010s, and 24 southern Canadian LNG projects were issued export licenses.

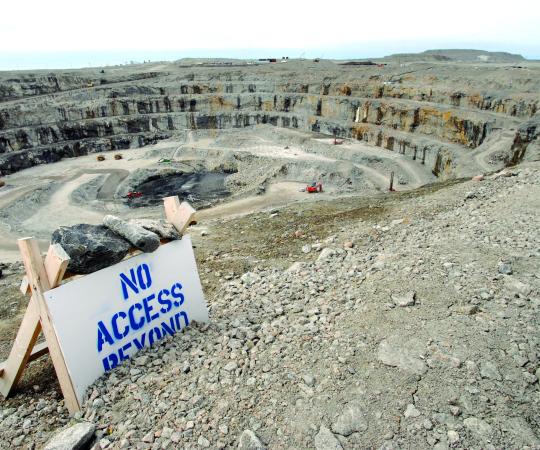

But why haven’t any big northern Canadian gas projects made it, unlike their peers in Norway or Russia? You can play a game of energy-policy Clue and match the suspect and murder weapon. Was it the retired Supreme Court Justice with the inquiry? The Regulator with the seven-year-long review? Or the American wildcatter with new-fangled fracking technology that changed the game for traditional drilling? It doesn’t matter. Those cases are closed.

Or so it seemed. There now appears to be another opportunity. The world’s energy system is undergoing a once-in-a-lifetime shake-up as Europe tries to wean itself off Russian gas. The bus is coming around again. Will we catch it the fourth time?

I’m sorry to report the answer looks like “no.”

The Europeans are looking for large amounts of gas, right now. This plays to people who have existing production and export facilities that either have spare capacity or can be expanded relatively easily. We have neither. Reuters reported that Germany could be receiving new supplies of LNG from Qatar as early as 2024. It would take us that long just to agree to the terms of reference for a new review board.

Meanwhile U.S. President Joe Biden has promised to double LNG exports to Europe by 2030. It will be a lot easier and cheaper to expand existing wells and LNG export plants on the U.S. Gulf Coast compared to building a new megaproject North of 60 in eight short years.

Plus, the energy policy Clue game board has an expansion pack: climate change. Getting a new Arctic LNG project through the Canadian political system will be very tough sledding indeed. So, add “the Canadian Voter with the Mass Street Protest” to the list of suspects.

There might, however, be a fifth bus: hydrogen. Hydrogen can be a low-carbon source of energy, and countries from Germany to Japan are thinking of importing tanker loads of it as part of their long-term climate change plans. You make “green” hydrogen from renewable electricity. You make “blue” hydrogen from natural gas, after removing the carbon and storing it permanently underground. Then you convert either form of hydrogen to ammonia to make it easier to ship.

It’s not impossible to conceive of massive northern wind farms powering green hydrogen and ammonia plants. Or blue hydrogen facilities pumping gas out of the ground and then pumping the carbon back in. Both green and blue would require ice-hardened ammonia tankers very similar to the LNG tankers the Russians are already using to ship LNG from Yamal to East Asia.

While theoretically feasible, such projects would need to compete with regions having established energy industries who are already working the opportunity. Australia has already announced a green hydrogen partnership with Germany. On the blue side, Alberta and British Columbia have lots of gas, infrastructure and carbon storage potential. Players in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Norway and the United States are also in the game.

Northern Canada might, just might, have a shot at hydrogen. But only if we are more determined, nimble, and low-cost than we were for the first three or four times the bus drove past us without stopping.