On November 8 1972 at 3:30 pm, a twin-engine Beechcraft 18, operated by Gateway Aviation and capable of carrying about 10 passengers, took off from Cambridge Bay for a medical evacuation to Yellowknife. It was a typical winter emergency flight, with no visibility or landmarks under the dull grey snow of the evening and during the night, and not really legal, given the conditions. There were 900 kilometres of frozen tundra and forest to cross.

At 7:30 pm, the ambulance was waiting at the foot of the Yellowknife control tower. The plane was late. There was no response to radio calls. At 8 pm, the alert was given. The search would last over three weeks, in temperatures ranging from -20 to -30°C. The pilot, Marten Hartwell, 47, was from West Germany. He had flown a little in the Luftwaffe towards the end of the war, but his Canadian licenses were recent. He had just over 2,000 hours of flight time, including about 30 hours in the twin-engine Beech 18 aircraft, and only knew the Canadian Arctic regions where he had flown over the last two summers. He had no instrument rating and little night flight experience.

The aircraft had just over six hours of autonomy at 250 kilometres per hour, but was not certified for instrument flight and was not equipped with a wing de-icer. It had only basic navigation instruments: a gyrocompass which, like all giros, precesses over time; two radio compasses; and a magnetic compass that was of no use so close to the pole. A “C4 compass” corrected for precession would have enabled the pilot to steer a steady course for several hours, and should really have been onboard all aircraft flying in the Arctic, at least during the winter. However, this type of reliable compass had only been installed in one or two Gateway Aviation planes, and not on this Beech 18.

In Cambridge Bay, where the medical evacuation began, nurse Judy Hill was a 27-year-old English woman who had just spent a year in the Inuit village of Spence Bay (now Taloyoak). She was travelling with her two Inuit patients who urgently needed to be hospitalized: a 25-year-old woman, Néemée Nulliayok, who was about to give birth, was suffering from serious complications. The 14-year-old boy, David Kootook, was believed to be having an acute appendicitis attack.

That evening, two Gateway Aviation pilots just happened to be in Cambridge Bay. Marten Hartwell, with his old Beech 18, CF-RLD, had been trying to get to Swan Lake near the Arctic coast – not far from the Perry River – for two days in a row, but could not reach the camp due to bad weather. Ed Logozar, an instrument-rated pilot with a very modern Twin Otter fitted with wing de-icers and a C4 compass to compensate for precession, had also arrived from Yellowknife, but had to leave the next day for Coppermine with two Water Resources men and all of their gear. It was Ed who’d gone to Spence Bay to pick up the two Inuit patients and their nurse Judy Hill. Marten and Ed spent a while discussing which one of them would make the trip to Yellowknife, and Marten eventually decided to do it himself despite his lack of qualification and the poor equipment of the Beech 18 for a night flight in wintertime. One of the deciding factors was that Marten was stuck in Cambridge Bay anyway because of the bad weather around Swan Lake, and could therefore use his plane to go elsewhere that night, whereas Ed was scheduled to fly to Coppermine the next day with no weather restrictions. Another reason was that the Twin Otter only had a 1,000 km range, enough to reach Yellowknife by day and in visual flight conditions, but not sufficient for instrument flying with a requirement to provide for an alternate field and an additional fuel reserve sufficient for 45 minutes of flying.

Between Cambridge Bay and Yellowknife, the only landmark along the way was the small radio beacon by Contwoyto Lake. Its transmission signal was very weak and could only be picked up by a modern and sensitive radio compass and only within a fairly close distance. I had on occasions actually seen this small radio beacon by Contwoyto Lake before my radio compass even picked it up. Moreover, at night and especially in the evening, radio compasses become unreliable because of electromagnetic disturbances in the upper atmosphere.

The Beech 18 that Marten Hartwell was flying should also have carried two survival kits, but only the remains of one of them were found. Each kit contained six 200g cans of corned beef, four packet-soups, 12 stock-cubes, 350g of rice, the equivalent of five or six powdered potatoes, glucose pills, and a dozen small packets of raisins – enough for four people to survive in the cold for ten days or so. A small battery-powered emergency transmitter automatically activated in the event of an impact and transmitted signals on the distress frequencies, assuming the pilot had activated it before take-off. The transmitter could also be switched on and off manually.

One might wonder why such a long flight, at night and in known icy weather conditions, was undertaken in the first place. The answer is simple: the passengers’ condition was critical, and somebody had to fly the patients to a hospital. Marten Hartwell’s mistake was to accept the flight when he had little night flying experience, no instrument rating, and was flying an aircraft that was not equipped for night flight, let alone for instrument flight. The passengers should have been taken to Yellowknife by Ed Logozar in the Twin Otter, despite the plane’s slightly short range. But above all, the Cambridge Bay clinic should have checked for alternative solutions. On that day, a DC3 from Yellowknife on a regular weekly flight was scheduled to arrive in Cambridge Bay three hours later: it could have taken the nurse and her two patients south without any problem.

As the Beech 18 from Cambridge Bay expected by the ambulance in Yellowknife had not arrived and couldn’t be reached by radio, a search was initiated that very evening, on 8 November. A military Hercules began an overnight electronic reconnaissance flight along the planned route: flying at 7,000 metres over eight hours, it did several trips between Cambridge Bay and Yellowknife, following a parallel route every time, at 30-kilometre intervals. No signal from the emergency transmitter was picked up. The next day, other Hercules continued the electronic reconnaissance mission. The weather was atrocious: freezing rain, snow, fog and blizzard.

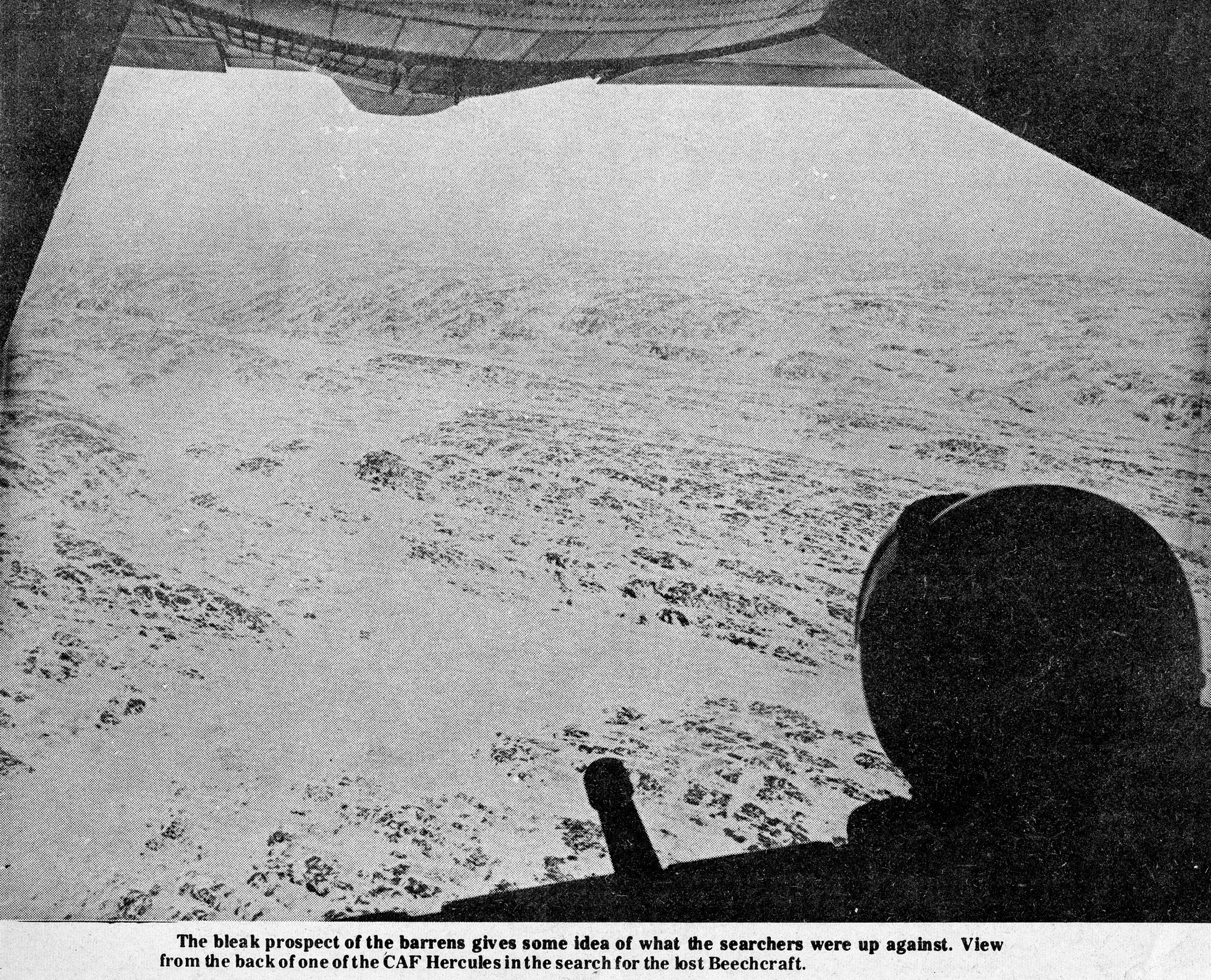

Later, the weather improved and a visual search began, along parallel 10-kilometre-wide strips at night at an altitude of 1,500 metres, in search of rocket flares or fires; and along 1.5-kilometre-wide strips during the day, at an altitude of 150 metres.

The search was initially concentrated along the direct route that the aircraft was to follow, within a narrow but widening sector with Yellowknife at the bottom and Cambridge Bay at the top. This was the “primary” area where the probability of finding the aircraft was highest. A fire was spotted at night in this area but, the next day, it was found that it had been lit by a small group of Inuit who were caribou hunting. Once the primary area had been screened, at the end of the first week, the search shifted to a wider strip, into the secondary and then tertiary areas. This took another week. The search team then initiated a more detailed examination of specific areas and then began looking for the wreckage in the hills along the Arctic coast, as well as exploring the forest near Yellowknife. Five Hercules, five Twin Otters and many civil aircraft took part in the search. Helicopters were on standby in Yellowknife.

Every day, some 50 civilian volunteers were employed as observers. In the Hercules cockpit, next to the two pilots, one observer would look to the left and the other to the right, up to about one kilometre away from the aircraft. In the back, lying on mattresses with their heads hanging out of the plane, three other observers would look below. They were secured with a harness, as the cargo door was wide open. I know this because I spent a whole day on my belly looking for my colleague Marten and his passengers with my wife, our heads out in the air. The pilots, mechanics, navigators and observers were all connected through an intercom system. Observers took turns every 20 minutes then rested for 40 minutes, during the eight hours of each flight. Paratroopers aboard the Hercules were ready to jump with rescue equipment.

Public interest, as always in these cases, was periodically revived by unconfirmed discoveries. On the third day of the search, for example, three Hercules in the Contwoyto area picked up distress signals. The signals, heard at 9:48am, lasted one second. At 1pm, further signals were heard for five seconds. Once again there was hope. But the emissions were too short to establish a position. Laboratories in the south identified five possible sources based on the position of the aircraft that picked up the signals, but the Beech 18 was nowhere to be found. After that, no further signal was picked up. Often, an aircraft would think it had seen something, but it was just a reflection on bright ice, or the shadow of a rock. Two psychics called from England, but their kind advice did not help find the plane.

On November 27, the search was called off after 19 days and 950 flight hours. Two hundred thousand square kilometres of tundra and forest had been covered. The government had spent about $2 million on the rescue mission. Meanwhile, Gateway Aviation had purchased a new light twin-engine plane, with the compliments of the insurance company.

The Ministry of Transport needed answers: who was to blame for this accident? There was probably shared responsibility: did the nurses and doctor in Cambridge Bay lead the pilots into believing that it would be criminal to abandon two critical patients? They claimed not. And one could hardly blame them for having only a faint idea of the issues surrounding air navigation in the Arctic in winter and at night. The Beech 18 had landed in Cambridge Bay from Yellowknife that morning and was there by chance. On the face of it, there was therefore no reason why that same plane couldn’t make the trip back a few hours later.

So, who’s responsible in these cases? Certainly not the airlines, which are essentially only in charge of maintaining the aircraft: if a pilot violates rules of the air at the request of his company or passengers, or if he makes a pilot error due to fatigue or to the stress of a particularly dangerous flight, he is responsible: he risks his licence, his job, and legal proceedings if there are victims. When he takes off with the intention of carrying out the planned flight, the pilot accepts the aircraft as it is, and confirms that everything is up to standard: the airframe, engines, instruments, radios, and cargo. It is also his responsibility, prior to departure, to ensure that all aircraft documents are up to date, and that the mandatory mechanical inspections every 50 or 100 flight hours have been recorded in the logbook which, incidentally, is no guarantee that they have actually been carried out. He accepts take-off runways that are too short or badly paved, engines that are known to occasionally run rough or break down, instruments that fail or freeze, and radios that don’t work. He also accepts the weather conditions expected during the flight, and the landing strip on arrival: a sandbank on a river, a more or less frozen lake, the crest of a moraine of large rocks, or dull grey tundra covered in snow, with no shadows and therefore no visible relief.

The pilot always has a right to refuse or interrupt the flight, but if he does this too often, he risks losing his job and being replaced by a young innocent and enthusiastic volunteer. At the beginning of my career, when I was looking for work as a pilot, I was thus offered a job regularly transporting dynamite and passengers for a mine in the Brazilian jungle. When I asked why the previous pilot was no longer flying, I was told that he and his passengers had been blown to smithereens when the 500kg of dynamite he was carrying exploded. It was put down to the local heat and humidity causing the nitro-glycerine to ooze from the dynamite sticks. I was prepared to take the job, but found another one in the meantime in Yellowknife: if I was going to be transporting dynamite, which I did many times, I would ultimately rather do so in the coolness of the Great North.

Responsibility for an accident therefore almost always falls on the pilot, and almost never on the company. It’s very unfair, and it’s inconceivable that a charter company could send pilots and passengers to their deaths without suffering the wrath of the Department of Transport, on the grounds that pilots are solely responsible when they accept the plane and the flight. During the inquiry that followed Marten Hartwell’s accident, Gateway Aviation, as always, explained that it had done nothing wrong: no one had forced the pilot to accept the flight; on the contrary. The managing director of the company, Doug Rae, clearly explained that he had just recently reminded the pilot to “be careful and only do visual flights in the daytime”. In the Arctic and in winter? That would mean staying grounded for six months without pay, or rather getting fired after a week! Just before Marten Hartwell, the company had hired an Australian pilot. He had killed himself and his passengers in a Beaver after three months, when he crashed into a hill on a bad weather day about 100 kilometres from Yellowknife. Again, it was the pilot’s fault: he had been asked to make the flight, but he should simply have refused.

I myself suffered 13 engine failures in November and December 1969 on scheduled flights between Yellowknife and Fort Smith with that same airplane, or one of the others of similar models operated by the same company, due to carburettor icing in one or the other of the engines while flying near Great Slave Lake. I had to cross the lake in both directions while it was not yet completely frozen, with about ten passengers every time. I eventually decided to cut one of these flights short when I lost the first engine ten minutes before arriving in Fort Smith. We landed normally with one engine. After the stopover, both engines started again without any problem, but I then lost the second engine shortly after take-off. With engine failures having occurred on both sides, things were getting risky, so I promptly turned around and returned to Fort Smith. During the return trip, the first engine also decided to stop. We glided down silently right onto the runway centre line, and the landing was actually very pleasant for everyone as there was no turbulence and the flight was very quiet. The passengers were delighted, though they regretted that the flight had to end there, and no one asked any questions.

Once we were on the runway with both propellers stopped, I had to wait ten minutes for the ice in the carburettors to melt before I could start the engines again to clear the runway and taxi to the ramp. The mechanic and the manager of the Yellowknife base I had come from were fully aware of the problem, which had been going on for weeks. But without a hangar, go try fixing an engine at night in minus 40ºC weather! Had we crashed in the forest or into Great Bear Lake, I would have been solely responsible: no one had forced me to fly.

On another regular winter flight with a Gateway Beech 18, the windshield de-icer worked only on the right and only slightly, clearing a tiny vertical ellipse in front of the co-pilot seat. I could see nothing through my windshield. When we were trying to land on the gravel runway at Fort Resolution, on the south shore of Great Slave Lake, I was directed by the cooperating passenger on my right, who was happy to be of service. He was leaning forward, peeking through the small hole: “a little to the left…”, “a little to the right…”, “about 800 metres…”, “a bit more to the right…”, “400 metres…”. I kept the altitude at about 15 metres above the fir trees by looking down to the left side window, in front of the wing, until I saw the edge of the airport pass by. Had we hit a fir tree, I would have been solely responsible.

Marten Hartwell was flying in similar conditions, with the same type of aircraft from the same company, but he had much less experience. Shortly after the search was called off, his adventure took a spectacular twist. At the insistence of an indigenous organization, friends of Marten Hartwell and, most importantly, the father of his friend Susan Hayley, the search resumed after a few days. On December 7, a military aircraft on a regular flight from Inuvik to Yellowknife that was totally unrelated to the search picked up a distress beacon signal. The Hercules changed course to better determine its origin, but the signal quickly stopped. The next day, two Hercules from the new search team flew around the region, completely outside all previous search areas, but heard no signals. On the third day, December 9, a Hercules picked up the signal again, sustained for longer this time, and eventually spotted Marten Hartwell waving a red flare in front of his tent next to the wreckage of his plane, south-east of Great Bear Lake, 300 kilometres away from the direct route from Cambridge Bay to Yellowknife. Another Hercules immediately dropped paratroopers in a small nearby clearing. It took them an hour wading through the deep snow to reach the wreckage of the Beech 18.

Marten was the only survivor. He told his story: Nurse Judy Hill, who was sitting in the co-pilot seat, had been killed on impact. The Inuit woman who was about to give birth died within a few hours. The 14-year-old Inuit boy, David, had some bruises but was not injured. As for Marten Hartwell, both his ankles and one of his knees were broken, which completely immobilised him.

Under Marten's direction, David, the young Inuit, had built a tent structure with pieces of fir tree, and covered it with the tarpaulins used to protect the engines. They had five sleeping bags on board. David starved to death after three weeks; Marten survived from the nurse's flesh. As he had a poor understanding of his distress beacon’s functioning and how to operate it – he in fact had additional batteries –, he’d only activated it for brief moments, and only on the rare occasions when he heard an aircraft in the distance.

During the flight, he was unable to pick up the very weak Contwoyto Lake beacon, and the Yellowknife beacon was far too distant, so he’d decided to descend from 1,200 metres to 700 metres above sea level to “better pick up the signal”. Instead, he should have gained altitude. Off-course towards his right and close to Great Bear Lake, he hit the top of a hill.

This story made headlines all over the world. It was around the same time that an F27 crashed in the Andes, on a flight from Montevideo to Santiago, with a rugby team and their friends and families on board. Of the 45 passengers, 16 were recovered after 72 days. They too had survived by consuming the flesh of the passengers who’d died in the accident.

Marten’s rescue was followed by an inquiry that began on December 11 in a hangar at Yellowknife Airport, was put on hold, and resumed on February 26 after further delays. Along with the men in charge of the judicial inquiry itself, several representatives from different branches of government were present: the Mounted Police, The Department of Transport, the Government of the Northwest Territories, and the federal Department of Justice. There were also representatives from the Inuit Tapirisat. The inquiry was led by Walter England, and the jury was comprised of six local men, five of whom had ties to aviation, including several pilots such as Rocky Parsons, Bob O'Connor and Dunc Grant. Marten Harwell was represented by lawyer Brian Purdy from Yellowknife.

The jury concluded that Marten was not qualified for the flight and should have turned it down, and that the aircraft did not have the mandatory navigation and communication instruments or that they were not functioning. The jury also recommended, among other points, that the small beacon on Contwoyto Lake, halfway between Cambridge Bay and Yellowknife, be more than doubled in power, from 400 to 1,000 watts. This beacon was of virtually no use: small commercial aircraft on wheels, skis and floats operating at relatively low altitudes barely picked up signals from the beacons within a 10km radius.

Naturally, Marten should have refused the flight, and the patients should have been sent to Yellowknife that very evening, either in the Twin Otter that was already in Cambridge Bay or in the DC3 operating NWT Air’s scheduled flights a few hours later. He should also have gained altitude to better pick up the signal from the Yellowknife beacon. With that being said, he was certainly influenced by insidious factors. First, at such high latitudes, gyrocompasses theoretically precess by a dozen degrees to the right every hour on a southbound (or northbound) flight, so that after three hours of flight his gyrocompass would have been steering him nearly 30 or 40 degrees to the right of his route. Second, the setting sun was just below the horizon to the west, and the sky was therefore relatively light to his right; conversely, everything was dark to his left. The appeal of light is very powerful, and a worried and stressed pilot would naturally tend to turn at least slightly to the side of brighter skies. What’s more, the tundra, pitch-dark at night and offering no landmarks from above, was to his left, whereas the forest, above which it’s much easier to navigate because one can identify the white lakes from the dark forest, was to his right. A pilot will obviously tend to drift towards an area where he can find his bearings, even if it means correcting the trajectory later on. I’d actually shared these suggestions with the search leader, who, accordingly sent out a Hercules the next day to spend eight hours west of the direct route, but nothing was found. It should have searched even further.

Marten recovered soon enough, after a few sessions of surgery to break his legs and straighten them back into shape. He got his license back, and started flying again less than two years later in Fort Norman on the Mackenzie River, west of Great Bear Lake. He was well accepted and respected by all, especially the indigenous Dene people, as he sometimes took risks to help them when they were stranded in the forest. In October 1987, in the snow and in very bad weather, the pontoons of his floatplane hit a fir tree as he was returning to Fort Norman after taking fresh supplies to a trapper. He was only slightly injured and was picked up after walking in the forest for two days. His return to Fort Norman was a joyous celebration.

Dominique Prinet flew for Gateway Aviation in Yellowknife from 1966 to 1971 with Beavers, Otters and Beach 18s on floats, wheels and skiis. Between flights he obtained an engineering degree from UBC and an MBA from McGill. Dominique became VP of Nordair (Montreal) in the 1970s and joined Canadian Airlines (Vancouver) as VP Marketing in 1987, followed by a stint in Africa. He retired in Vancouver, published several books on Coastal and Celestial Navigation and obtained his helicopter licence at age 70. In 2021 He published Flying to Extremes (Hancock House) describing his adventures as a bush pilot in the Arctic during the late 1960s.