Last year, residents of São Paulo, Brazil, drilled holes through their basement floors trying to drum up groundwater. Out of the estimated 800 million residents of Africa, 300 million live with water scarcity. California’s drought has put it in a formal state of emergency.

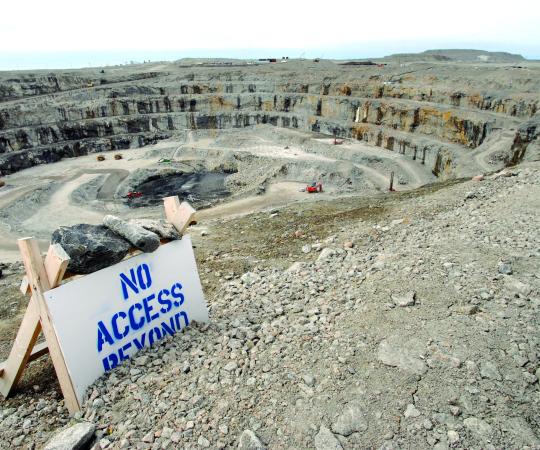

Meanwhile creeks appear out of nothing in the Yukon’s Kluane National Park, as glaciers thaw in the mid-day summer sun, and I can walk down to Great Slave Lake from my Yellowknife home and dip my cup right into the water. Northern business headlines have all centred on the mineral and petroleum industries—the mineral commodities market is in shambles, and the global oil glut has made development of remote Northern reserves in the near future a laughable prospect. Somehow, no one is talking about exporting our clean, fresh Northern water to the rest of the world. But it’s only a matter of time.

Former Manitoba premier Gary Doer, more recently Canadian ambassador to the United States, has been telling anyone who will listen that water will be the biggest issue between the two North American neighbours in the long run. And despite it not being a major item in the news, if you start looking at the numbers you suddenly begin to see there’s an elephant in the room.

Nearly 70 percent of the world’s surface is covered by water, but only 2.5 percent of that is fresh water. And less than half of that is really accessible—the rest is locked in glaciers or snowfields. Canada holds close to one-fifth of the world’s fresh water—but only 7 percent is renewable, or not locked in underground aquifers, frozen in glaciers or stored in lakes unconnected to the larger water cycle. And about half that renewable Canadian water flows north to the Arctic Ocean and Hudson Bay, making it completely unavailable to 85 percent of our country’s population. When the conversation eventually turns to bulk water exports from Canada, it’s inevitably going to mean bulk exports from Canada’s North.

Our water would no longer be just ours by right, and public outcry might not be able to stop its export without international economic consequences.

Now, you’ll hear that water is a renewable resource. And it is—water is not destroyed by human use and the Earth is a closed system—but it’s also not quite that simple. Water falls from the atmosphere to the ground and runs off into rivers and lakes that drain into the ocean. There, water is evaporated by the Sun, rises to the atmosphere, then falls back to the ground as rain or snow. Generally, this is a one-year cycle, though in some places this water sinks into underground aquifers and reservoirs and stays there. If a climate changes from humid to arid (as has happened throughout the world’s history), these underground reservoirs can’t be considered renewable—they’re all the water that region will get for generations.

And fresh water isn’t just for drinking, bathing and brushing your teeth. In fact, that accounts for just eight percent of global use, while 22 percent is used for industrial purposes and a whopping 70 percent is used in agriculture.

Like global warming before it, the murmurs are beginning, hidden at the bottom of an interview with Doer, or in academic papers, such as one by Arizona State University law professor Rhett Larson last August, The Case of Canadian Bulk Water Exports. Larson argues Canada can responsibly export its water with three reforms: making it a “good” as defined by international trade treaties, which he says would help people better value water and waste less; distinguishing between intra-basin water transfers (between Canada and the U.S. within shared watersheds) and inter-basin (exports governed by international trade agreements we could restrict in case of critical shortage); and accounting for the water exported in products like produce, to give us a more accurate picture of what’s leaving the country. (This accounting of what water is going where could also help us figure out what regions are becoming too dependent on our water exports.)

The very premise of Larson’s argument has frightening implications. To make water a commodity rather than a human right would subject it to the same corporate and international trade laws that govern the rest of the resources Canada exports. Our water would no longer be just ours by right, and public outcry might not be able to stop its export without international economic consequences. If we’re going to export water, how else could we do it but as a product? It’s unlikely job-insecure Canadians would be okay with just giving it away without compensation. British Columbia has been experimenting with a middle ground in its limited dealings with a Nestlé water plant to export some water under the same scheme as other industrial water uses. And residents are already disgusted with the province’s sliver of that pie: about $2.25 per million litres, in access fees. The government stands by treating water differently than other resources. “What would happen,” asked B.C. Environment Minister Mary Polak, apparently rhetorically, to media, “if you start to generate a profit, start to generate revenue from water? What behaviour does that create in government?”

Arguments in favour of exporting Canada’s water could be made by the moralist and the profiteer, and they will. Can we sleep at night surrounded by pristine water while more than two billion people struggle to live for lack of clean, fresh water? If Canada’s resource-based economy takes more hits and the numbers of jobless citizens grows, will the temptation of this lucrative export—and its pipeline construction—prove too great? This conversation is going to happen, first in Ottawa, then in the North. And it’s going to shake our whole system. Aboriginal groups who’ve been asserting their treaty rights on land and water are going to be confronted with an even greater threat to the traditional lifestyle—and natural world—they’re trying to defend. Other Canadians, who largely define themselves as outdoors people, are going to see their canoe routes and fishing spots under siege.

These statements are dramatic, sure. But water sustains everything. Life can’t exist without it. And while the water won’t disappear, commoditizing it irresponsibly could alter our landscape in ways that won’t recover for generations—and cause internal strife at a level the country’s not yet seen. But if we hold it close and don’t share, the faces looking in at us from outside may grow emaciated, desperate and angry.