At first, it was just another shooting star. But as it moved past the constellations, behind ribbons of aurora, it became larger, brighter. It was heading for Earth. A few prehistoric creatures, swimming through the water on an Arctic bay that would one day be named for a British nobleman and cricketer, might have looked skyward, with the impression that something was off. But it was likely too late. When the meteorite hit Earth, the impact was so strong it summoned up a ring of magma from beneath the planet’s crust.

That’s a theory. Maybe none of that happened. Right now no one knows exactly what caused an anomaly that makes compasses spin wildly and affects the very gravity of the area. Or what it is. We know it’s big. The blip in gravity right by Paulatuk, NWT, hints at dense rock, and the magnetic disruption hints at iron—symptoms of nickel-copper-platinum mineralisation. Looking at similar anomalies around the world—like the Sudbury Basin in Ontario or the Olympic Dam in Australia—it might signal the biggest mineral treasure trove Canada’s North has ever seen.

The year is 1954. Marilyn Monroe and Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio tie the knot in San Francisco. Edward R. Murrow and his news crew release a prime-time special going after Senator Joseph McCarthy. And over the tundra coast of the Arctic Ocean, a man named Hank Vuori sits in a Husky aircraft watching a compass go haywire. This is the first hint of something big in Darnley Bay.

In 1969, year of the Manson murders and Woodstock, the Geological Survey of Canada confirms the presence of a massive geological anomaly. Yet today, in the age of the iPhone, a drill still hasn’t touched whatever it is that’s under there.

The Sudbury Basin in Ontario (which is generally accepted as caused by a comet impact) has produced over $120 billion worth of nickel, copper and platinum group metals over the last 100 years, according to CaNickel Mining Ltd. It’s 27 kilometres wide, 60 long and 15 deep. At 40 by 80 kilometres in surface area, Darnley Bay could be host to the same minerals (plus some diamonds, indicated by nearby kimberlites), but in much larger quantities. It could be huge.

Leon La Prairie, who worked for Vuori back in the day, founded Darnley Bay Resources Ltd. Between 1993 and 1997, they negotiated exploration permits and staking rights, and today they hold exclusive mineral rights to every part of the anomaly that’s not under the Inuvialuit community of Paulatuk, NWT, or off the Arctic coast.

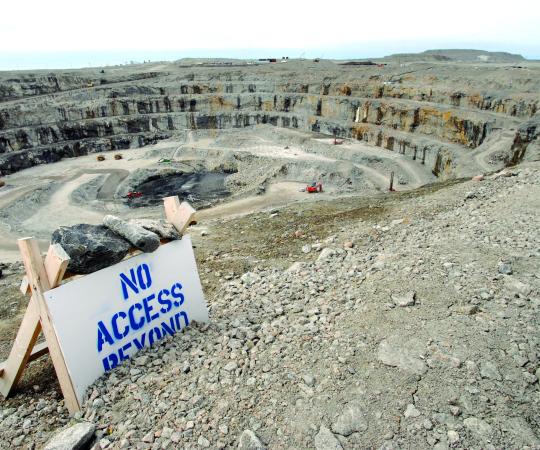

But it’s expensive to get there, expensive to operate there, and the anomaly is an expensive structure to explore. They got a drill close to the anomaly in 2011, but, according to Stephen Reford, the company’s chief technical officer, the instability of the permafrost they were drilling through forced them to stop.

The company conducted a magnetotelluric survey in 2013—measuring electric and magnetic fields—and that was the last work it’s done up there, says Reford. “And since then, the market has just been horrible so it’s really hard for junior companies.” But they putter on, the prize never too far out of sight. The company has been acquiring smaller nickel projects in Quebec, hoping they can make a bit of profit to then invest back up North. When they finally drill into the Darnley Bay anomaly and solve a generations-old mystery, they hope it will exceed even their wildest dreams.