If you were to scan the headlines over the past few years for news of northern mining, you’d see a lot of coverage of gold. That would be the case for two of the territories, at least. The Yukon has experienced a gold rush that has driven GDP growth projections as high as 7.8 per cent for the next five years. Nunavut, meanwhile, has witnessed the opening of two new gold projects, the rescue of a third, and sees a fourth on the horizon.

The story is different in the NWT, a jurisdiction with a deep history as a producer of the precious metal. Gold may be the top exploration story in the territory—but where’s the buzz? Companies such as Gold Terra Resource Corp. and Nighthawk Corp. have made significant advances. There are also encouraging developments from smaller projects by companies such as Rover Metals Corp. and Sixty North Gold Mining Ltd. Yet the NWT just doesn’t seem to attract the attention its territorial neighbours currently enjoy.

The numbers tell a grim story. In 2021, the NWT attracted a slender $66 million in exploration investment, well behind $123 million in Nunavut and $139 million in the Yukon. With gold prices at US$1,8000—a 50 per cent increase since 2018—one might expect investment in the NWT to be somewhat stronger. Yet only a handful of companies are active, compared to more than a dozen in the Yukon and several more in Nunavut.

Why?

The answer to that question is layered and subject to various interpretations. One of the first things to bear in mind is that two companies have major advanced exploration projects in the NWT—Gold Terra and Nighthawk. Gold is also a substantial part of the metals mix at Fortune Minerals Ltd.’s NICO property—about one million ounces—although the project is better known for its reserves of critical minerals used in green-energy technology and is still working on financing to start production.

Despite the potential of these projects and others, the NWT seems to lack the narrative that drives the excitement around developments in the Yukon and Nunavut. In the Yukon, especially, that story has all the elements of a blockbuster mining tale.

In the first decade of the 2000s, a self-taught geologist and prospector named Shawn Ryan began staking claims in the region around Dawson City. His goal sounded like a fantasy: to discover the motherlode that fed the creeks and streams that, more than a century ago, inspired the historic Klondike Gold Rush. By the time Ryan located the White Gold deposit, his first major discovery, junior exploration companies were already following in his footsteps. By 2010, the Yukon was experiencing a proper rush. In 2009, mineral explorers set a record, staking just shy of 80,000 claims. They smashed through that in 2010, staking 110,000 claims in the first seven months of the year alone.

A softening of gold prices around 2012 cooled the fervor, but it wouldn’t last. By 2016, the rush was back on form. This time, major miners such as Goldcorp Inc., Newmont Mining Corp., and Barrick Gold were on the scene, investing hundreds of millions of dollars to acquire advancing projects. In 2020, Victoria Gold Corp. put its Eagle project, the largest gold mine in Yukon history, into production. More mines are almost certain to follow.

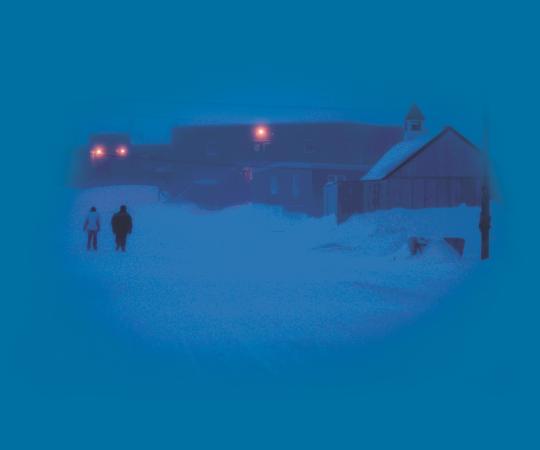

While exploration companies were setting records and making deals in the Yukon, Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd. was advancing its Meliadine gold project near Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, to production. With a mineral reserve of four-million ounces, that project is scheduled to remain in production to 2032. Agnico Eagle was also developing its 2.9-million-ounce Amaruq project, a satellite of the company’s Meadowbank mine, and generating more positive news. The company made further headlines in 2021 when it stepped up to buy the financially troubled TMAC Resources Inc. and breathe new life into the Hope Bay mine.

Given the developments, it is a small wonder that Nunavut and the Yukon dominate the northern mining headlines. And exciting stories help generate interest in the investment potential of a region. “You need to see splashy headlines,” says Dave Webb, president and CEO of Sixty North Gold. “Quebec has made these discoveries. Red Lake has ‘x’ number of claims and the largest undeveloped gold deposit…. You need that kind of news coming out.”

The NWT does have positive news. Lots of it, in fact. Webb’s company, for example, is putting its Mon property near Yellowknife into production, although the scale of its operations—for the moment, at least—is small enough to be described as almost “artisanal.” (Sixty North has a known gold deposit and is in the fortunate position of being able to economically mine and process ore in small volumes while it explores the formation in greater depth.)

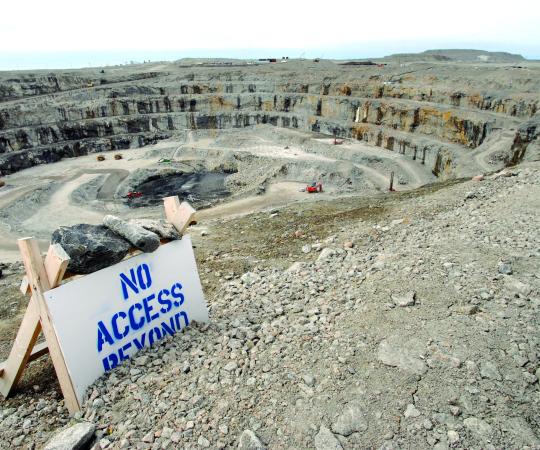

Before Christmas, Gold Terra also made headlines in the NWT, announcing a deal under which it received an option to acquire the old Con Mine from its current owner, Newmont. The property, on the outskirts of Yellowknife, produced more than five million ounces of gold during its 65-year life. It also covers part of the formations that Gold Terra has been exploring, developing probable resource estimates of 1.2-million ounces. Senior company officials have even speculated about the potential of reopening Con Mine’s Robertson shaft, although its landmark red-capped headframe, a symbol of the city to many Yellowknifers, is long gone. Nighthawk, meanwhile, has continued to add to its probable resource estimates at its Indin Lake property, which now stand at more than 2.2 million ounces. Last year, it also raised $27 million to fund exploration.

This is all good news and should be a stronger theme in the NWT gold story. But perceptions are tricky things. Webb wryly notes that television programs like “Ice Road Truckers” and “Ice Pilots” may be great for promoting adventure tourism—COVID-19 notwithstanding—but they can create challenges for other sectors. “They make it look like it’s a very tough place to work and only real men and women can make things work,” Webb says.

That’s an interesting observation. The larger issue, however, is the actual nature of the projects across the territories. The Yukon has had a rush that is leading to new mines. Nunavut is celebrating the opening of new mines, too. In the NWT, the story is still about exploration. “Slogging through exploration is generally not a headline generator for the public, unless they are investors,” says Tom Hoefer, executive director of the NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines. “Yukon had a staking rush… We haven’t since diamonds [in the 1990s.]”

In the big picture, exploration investment drives discovery, and discoveries generate attention, often leading to more exploration. But when it comes to NWT—as well as the Yukon and Nunavut to varying degrees—there are challenges to attracting that investment that must be overcome: a lack of infrastructure, especially roads, unsettled land claims, and a regulatory system that potential investors tend to regard as difficult.

There is also a sense among some observers that the current NWT government hasn’t made a priority of mining. The previous legislature, in 2019, passed a new Mineral Resources Act, outlining how exploration and development are to occur going forward. But the Act won’t come into force until the nuts and bolts of the process are laid out in regulations, which the mining industry is still waiting for. That’s earned the government some criticism, notably from current and former NWT politicians, although, in fairness, COVID-19 has laid waste to many schedules.

Nevertheless, the NWT has suffered a weakening of its reputation as an investment destination beyond current circumstances. The trend in exploration spending noted above is only part of the evidence. According to the Fraser Institute, for example, the NWT’s position has been falling on the Vancouver-based think-tank’s annual ranking of industry perceptions of mining jurisdictions in recent years.

The availability of access to land for exploration is one of the factors leading to the weakening perceptions. More than two-thirds of executives in one of the Fraser Institute’s surveys cited a degree of concern over the amount of NWT land being withdrawn from exploration to create protected areas or set aside pending the outcome of land-claim negotiations. That attitude was also noted in the “2020 NWT Environmental Audit: Technical Report,” a legally mandated independent review of the territory’s regulatory regimes that takes place every five years. The report’s authors said that industry raised concerns over land withdrawals during consultations, especially withdrawals made outside of broader land-use planning processes.

The audit also described a “disconnect” between industry perceptions of the NWT’s regulatory regimes and efforts by regulatory boards to clarify and bring certainty to the process. In particular, it singled out the burden placed on small, low-impact projects, which can be required to undergo the same levels of permitting as much larger advanced projects. “Despite the efforts of [land and water boards], small exploration companies continue both to struggle with the application process and to meet its requirements,” the report’s authors wrote. “If allowed to persist, this disconnect between industry and regulators will continue to affect exploration activity in the territory which, in turn, affect the NWT’s socio-economic environment.”

Gloomy as all that may sound, it’s not reason for pessimism. The mineral potential of the NWT remains widely recognized. And the challenges to attracting investment are substantially around policy issues—issues where industry, communities, and political leaders have the potential to find common ground or compromise.

Also, some would question how perceptions are evaluated. Among them is Caroline Wawzonek, the NWT’s minister of industry, tourism, and investment. “There has been a lagging in terms of our exploration activity for a while. But specifically with the gold industry, I think there’s a question of how we measure it,” she says. “We do not currently have active gold mines. Compared to our neighbours, however, there is actually a lot of activity and some of that, I do feel, is happening under the radar.”

Looking forward, Wawzonek says she expects the territorial government’s Mineral Resource Act and the Public Land Act, also passed in 2019, will benefit the mining industry once regulations are developed and the laws come into force. She also notes that the NWT is at the forefront of trends in ESG—environment, social, and governance—benchmarks that have become leading considerations in investment decision-making.

She also disagrees with those who argue the current government hasn’t been supportive of mining. “I’d say there’s a lot of enthusiasm. I think overall, certainly cabinet is very strong in supporting economic development, but in supporting economic development that puts us… on the leaderboard for the kind of development that [reflects] where investors are going.”

In other words, the story of NWT gold is not simply about drilling programs and strike zones. Those are important, but the territory hasn’t yet hit the production decisions that will grab the headlines and generate the kind of buzz seen in the Yukon and Nunavut. Based on the determined exploration that’s already in the field, however, that day may well come. Until then, there’s a story to promote in the NWT’s record on ESG. And there may also be a story on regulatory developments to assuage industry concerns. Let’s just hope that happens sooner rather than later.