A shopping bag of beer in one hand, I tear at the starter cord of my boat motor with the other. My life jacket zipped up—yes, mom, all the way to the top—and throttling away from the dock, I wind my way through the houseboats of Yellowknife Bay. It’s Scrabble night and I’m heading to the mainland for a game.

I belong to a tight-knit gang of past-middle-age Scrabble players. A nearly-dead poet’s society. We have no special handshake, but our secret association does resemble the Freemasons in other ways: we are exclusively male, pretty darned white and quite hush-hush about our goings-on. What happens at Scrabble, stays at Scrabble. Until now.

Pulling up to shore, I disembark from my barque before opening the door to our lodge. A billowy fog of cigarette smoke pours out into the night, stinging my eyes and nose. I love Scrabble and the sound of the thin wooden tiles clicking like tiny castanets in the bag. I love hanging with these fellow word-nerds. Old school. Old guys. Old Town YK.

Our weekly games are about camaraderie, but also competition. We record scores and every word played in a well-worn notebook. We rely on the official Scrabble Dictionary as an arbiter to challenge one another when bull gets shit (unless the bullshit is in the Dictionary).

I didn’t always love the rules. When I first joined the group, I was aghast at the kind of sanctioned Scrabble vocab that passed for English—za, slang for pizza; aa, a Hawaiian borrow-word for lava; and seemingly the entire Hebrew alphabet. I rankled at this twisted, deformed excuse for Shakespeare’s language. But my thinking has evolved over the years. I now recognize that arguing for the inviolability of English is like Frankenstein in reverse: making a corpse of an assorted, living thing. And rules were made to be broken.

English is a mongrel language born of a centuries-long coupling of French, Latin, Norse and German. It continues to grow, gathering new words and phrases like burrs as it passes through and settles in different lands. Dictionaries of Caribbean, Newfoundland and South African English document respective Englishes, infused with local colour and character. Different ‘spokes’ for different folks. Similarly, the Scrabble Dictionary represents Scrabble English. It is less a lexicon than it is a rulebook, so, I suggested to the others, let’s make up our own house rules.

I wanted Scrabble to be less American and more Northern, reflecting the uniqueness of where we live. I wanted to Indigenize it by introducing Dene words to the game—to breathe new life into the Scrabble monster. I pitched the idea to the team.

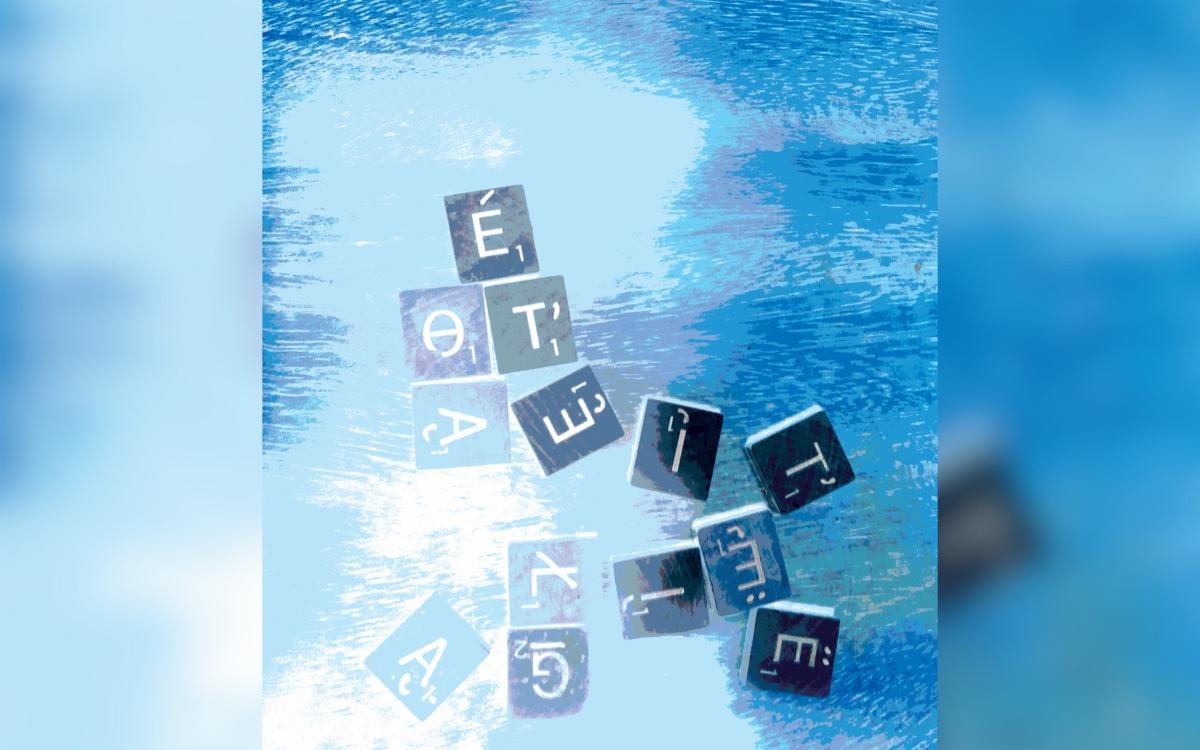

Some of the players were interested, if unfamiliar with Dene words—a consequence of the cultural solitudes that can be Yellowknife. Others though, have longstanding personal connections with Yellowknives Dene, Tłı̨chǫ and Dëne Sųłıné communities. More than keen to give it a whirl, one particular word-gamer emptied tiles out of his pockets, hand-painted with Dene accents that transformed L into Ł, O into ǫ̀ and K into K': “Those are diacritics, not accents,” we were reminded. Um, yeah? The guys brought enthusiasm and experience to the experiment.

In the early 1900s, French—not English—was the dominant colonial language in the Northwest Territories, introduced by fur trade merchants, Oblate priests and francized Métis who settled in the region. Sousi Beaulieu was a Métis guide at the time. He spoke a soupy kind of French, described not as a ragout, but as a suit of many colours, by his one-time employer, E.T. Seton:

”…the garment of his thought is like Joseph’s coat. Ethnologically speaking, its breath and substance are French, but bears patches of English, with flowers and frills and strophs and classical allusions of Cree and Chipewyan.”

That Sousi’s dialect was embellished with the “five different languages of the country” says that his was a Northernized French, a quilted language that matched— was reconciled with—the cultural makeup of the day. As a translator, it was part of Sousi’s job to understand—and be understood by—lots of people. If he spoke a bespoke French back then, how about a Northern English today?

I’m enthralled by Dene language, its cadence and complexity. And the possibility of reconciliation was not lost on me. Maybe introducing Tłı̨chǫ and Dëne Sųłıné words to our Scrabble Dictionary would help, in a small way, to northernize English and to pay some mind to the people and languages that were literally born of this place. It might also be fun.

In Dene languages, diacritics are special markings or glyphs that indicate a different tone entirely and change the sound of the letter. Ł (a breathy ‘kl’) sounds very little like L (‘el’). Our Scrabble group didn’t end up using the hand-painted tiles because we couldn’t figure out how to build English words off the Dene ones. Also, we accepted that this is how loan words work. Foreign words get flattened when they are anglicized. Cafe, doppelganger, and sushi are all written differently in French, German and Japanese. A Dene loaner like k’ı (meaning ‘birch’) ends up looking like ki, which is already a Scrabble variation of qi (Chinese life force). That’s too bad, because k’ı is a nice word and a root for compound words like k’ıkw’à (birch plate), k’ıelà (birch bark canoe) and k’ıtì (birch syrup). This textured frill gets crushed by mercenary game play; the first wrinkle in our technicolour suit.

Our secret society has messed with the official rules before. We all have access to a cheat-sheet of every Scrabble-sanctioned two-letter word in the dictionary. It’s a socialist leveler that allows new players to keep up with the old. (The dog-eared list is also scorched on one corner—evidence of an attempted burning by a conservative and slightly intoxicated gamer).

Hoping to encourage uptake of Dene vocabulary, diacritic-free amendments to the two-letter list included le (actually łe, flour), ke (moccasin), sa (sun) and xe (pus/boil). Longer-lettered additions made it too: xato (xat’ǫ̀, fall), x0ke (xok’e, winter), zah (snow), hozii (hozı̀ı, barrenlands) and kwetii (‘white people’ or ‘settlers’—literally ‘rock people’), all in hopes that higher-valued ‘k’,’w’,’x’,’y’ and ‘z’ would incentivize their use.

As self-appointed list curator, I then added recognizable words visible around Yellowknife. Niike (seen as nı̀ı̨kè bilingual stop signs), detoncho (det’ǫcho, ‘eagle’, and the name of Yellowknives Dene’s development corporation), tindi (‘big lake,’ and the name of local air charter company) and ko (like in Yellowknife’s Birchwood Coffee Kǫ̀). These words stood a good chance of recall.

Scrabble is better than cards because it doesn’t demand hawkish attention to the game. It allowed us time to talk about the Dene additions. We deconstructed some of the new words, which led to a few ‘aha’ moments. Who knew the Tłı̨chǫ word for the number five—sı̨làı—literally translates as ‘my (sı̨) hand (làı)’? Well, besides the more than 2,200 Tłı̨chǫ speakers, that is. What an extraordinary language that fills cold, hard numbers with the warm blood of a five-fingered hand.

Our little group of curious kwet’ı̨ı̨̨̀ got a glimpse at the sense within and behind Dene language. Words enfold stories, histories, places, worldviews and logic, just begging to be unwrapped. Imagine all the layers of meaning that could be revealed if only a Dene speaker had been there, at our Scrabble game, to tell us.

It got me thinking: Was it appropriate that we should muddle our way through these discoveries? Was it cultural appropriation to try?

Anishnaabeg broadcaster and author of Unreconciled, Jesse Wente disputes that reconciliation is what’s required in modern-day Canada. The ‘re’ in reconciliation, he says, suggests mending a broken relationship. What we need, instead, is conciliation, as a relationship has never existed in the first place. It’s why a land acknowledgement in a room of non-Indigenous people tends to ring so hollow. Or why a small, homogenous knot of guys deforming and playing with Dene language wasn’t going to address centuries of ignorance, disrespect and abuse. If adding a few words to one’s vocabulary were all it took to reconcile, things would have been fixed long ago.

Behchokǫ̀ elder and educator Rosa Mantla thinks about how to teach Tłı̨chǫ language, even in retirement. When I tell her about our language experiment over tea at the Walmart McDonald’s, she seems to like that we are interested in learning about Dene words. She’s curious to know more about it.

Tłı̨chǫ matriarch Elizabeth Mackenzie is credited with coining the expression ‘strong like two people’ to encourage Dene children to learn the ways of their ancestors and the ways of settler culture. Rosa agrees that kwet’ı̨ı̨̨̀, too, can be strong like two people, including learning Dene language.

Rosa also sees promise in all-Dene Scrabble as an educational tool for schools. We chat about how a school-based game could work with diacritics and how students might use existing dictionaries, flashcards and other resources to help put Dene words into practice. I’m also a teacher, so my mind fires up at the possibility of working to support the revitalization of Dene languages. I love the idea of interacting with Indigenous-language speakers who might reveal more of the stories and histories behind the words.

But, I wondered, is there still value in our group of players learning more Dene? More to the point, is there a role for kwet’ı̨̀ı̨ to play in supporting Dene language learning? I put the questions to Rosa. “Of course,” she answers. “It’s very important for adults to model language learning for youngsters and, yes, we need your help.” With a look somewhere between bemusement and frustration, she turns her eyes to me and asks: “But, why are you asking such silly questions?”

We still play our weekly game and continue to refer to the Dene word list. One rookie player—and the first female to join our ranks—recently used it to rack up big points with nezo (Dëne Sųłıné for ‘good’ or ‘nice’). Proof that Northern Scrabble can teach about Dene language.

Learning about Indigenous language is just the tip of the iceberg, though. It’s an initial step in acknowledging different ways of being, doing and knowing. What starts with new words could lead to new and wider worldviews. But, to truly (re)concile it’ll take connecting people, not just letters.

For now, we’ll Scrabble on, in Korean, French, German, Japanese, English and now Dene.