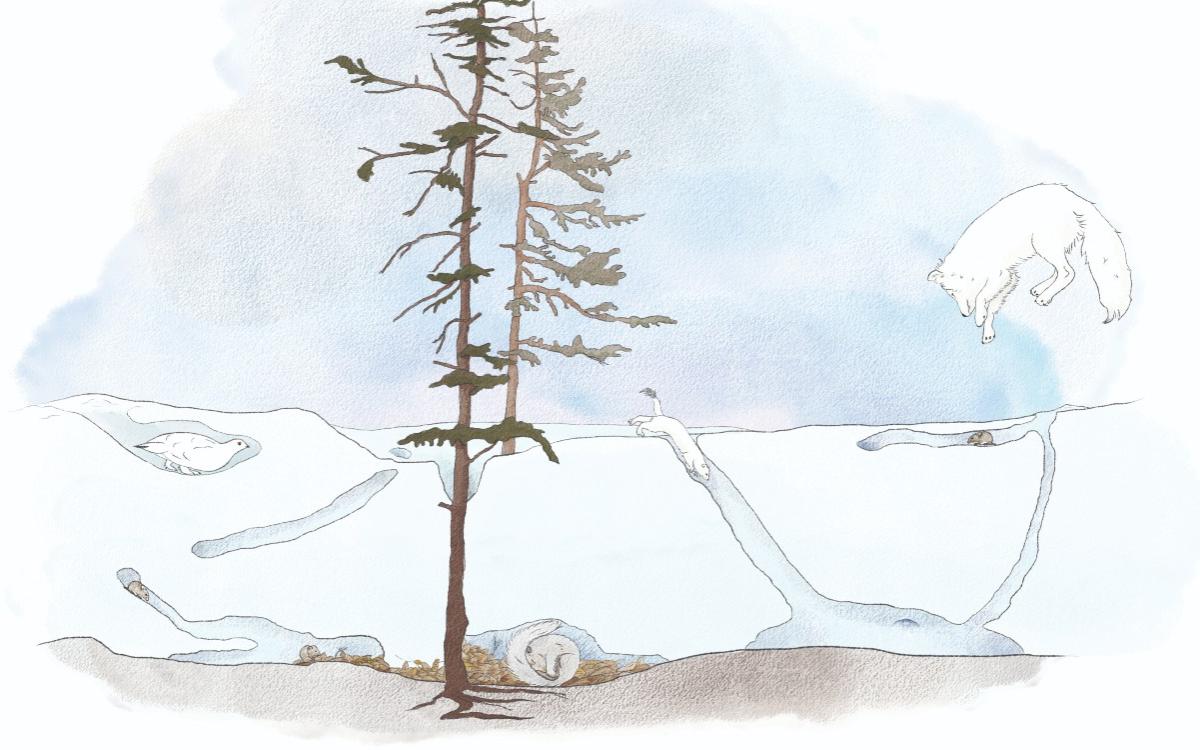

A white blanket stretches across an opening in the boreal forest, surrounded by black spruce trees, willows and alders. The snow lies about two feet deep in the opening. Beneath the blanket of snow there are squeaks, soft chittering and rustles. If we could peer down into its depths, it would be dark, but not nearly as cold as on top of the snow.

Well-cleared tunnels run through the remnants of summer grasses and around the stems of plants and the trunks of small trees. The tunnels are clear of frost spicules and detritus, obviously a place of life and activity. Meadow voles run rapidly along the sub-snow tunnels or nibble at the remnants of the green bases of the grasses or on the bark of willow bushes.

Above arches the great cold abyss of the subarctic winter, where the aurora paints the sky and stars scintillate against velvet. Beneath the snow, breaths of the voles fog the tunnels, but in the blackness, they cannot see, trusting to their whiskers to guide them through the web of tunnels. Carbon dioxide from their exhalations builds up, and it becomes harder to breathe. This triggers intense activity among the resident voles and the chittering increases. Voles run rapidly through the tunnels, nervous, hyperactive, fearful.

The chittering and squeaks drift up though the snow cover. A red fox trots delicately out of the trees and onto the meadow, his feet sinking only slightly into the powder snow to the more solid layer beneath. He stops, tilts his head, pricks his ears, and looks down at the snow, listening to the sounds beneath. His bushy tail lifts, floating. He tenses and moves his head and ears, searching, peering. He freezes, ears tight pricked…

Suddenly he rises up on his hind legs and arcs into the air, jumping high off the ground and arcing into a dive into the snow, front legs braced, face following the arc of his jump. His legs, head, and face disappear into the whiteness and he rocks back, pulling out with a vole grasped in his teeth, leaving a crater in the snow. Fresh air rushes into the hole left in the snow and refreshes the air in the tunnels below. Through the death of one resident, others have renewed oxygen to breathe.

The tunnels quiet and life goes on.

From the boreal forest to the tundra, a hidden world lies beneath the white blanket of snow that carpets the ground from November to April or May. Life continues throughout the northern winter in this twilight world, unseen and for the most part unnoticed even by those who live here.

This subnivean (“sub” = below; “nivean” = snow) environment is vitally important to many of the smaller animals who live in its shelter, and to predators who have learned how to use it as their hunting ground.

The snow carpet provides a much more stable environment than the world on top of the snow. There are no sweeping and desiccating winds. Temperatures vary only a little once the snow cover is established. The activities of animals are hidden from view. Humidity is almost constant, and much higher than on top of the snow. Life continues throughout the year for many animals.

As the snow falls and accumulates, different changes happen which contribute to the development of a “subnivean” environment. Snowflakes drift to the ground and begin to deteriorate, becoming rounded ice grains in the snowpack. Each coalesces with others and are compressed by wind packing and the weight of the accumulating snow. The snowpack “sets” within hours of the snowfall. Then, changes occur in the structure of the snowpack. Due to what can be an extreme temperature gradient—very cold on top where exposed to the air, and relatively warm on the bottom where it is in contact with the warmer ground surface—the chances of survival for warm-blooded animals are much greater when protected by this insulating cover. The humidity is greater as well – above the snow, all water turns to ice, and is essentially unavailable to most animals, but below the surface, humidity rises with the ambient temperature. Close to the ground the humidity is higher and the chance of an animal dehydrating becomes much less.

Distinct layers develop in the snow cover, light fresh snow on top (absent in most arctic environments where the snow is hard packed almost at once since it is delivered by strong winds). In the boreal forest, this fresh snow layer gives way to packed snow which has become harder through the evolution of snow crystals and settling. Under that is often a layer of hoarfrost, crystalline snow in which crystals grow over time, interlocking due to temperature changes. Under that is often a lens of harder snow from previous earlier snowfalls, and then a layer of “depth hoar” with metamorphosis due to heat radiated from the ground itself. The snow coalesces into crystalline curtains, shrinking back and allowing animals to live below its blanket and to travel underneath, against the ground. It is in this layer that most small mammals live.

In the depth hoar they are able to excavate tunnels and chambers (many lined with soft grasses or leaves), and are able to move about in relative safety and secrecy, protected somewhat from predators from above. Some amount of “almost green” vegetation survives and is fed upon by voles and lemmings. Deer mice feed on stored seeds, and red squirrels cache pine seeds in middens which serve as food sources in winter, often sleeping near or in these middens. Many insects overwinter in the leaf litter of the forest floor, and several species of shrews hunt for small mammals as well as invertebrates.

Although they might sink into torpor in very cold weather, few of these small mammals hibernate; their bodies are too small and retain heat too inefficiently to allow them to survive the deep chill. They must eat throughout the cold months to fuel their internal furnaces. The shrews in particular, are hard-pressed to survive, with almost 90 percent of their population sometimes dying in a cold winter. Their hearts beat close to 800-1,000 per minute; their metabolism is the highest of any North American mammal, and they must eat constantly to survive, sometimes eating more than three times their body weight per day, and sleeping only sporadically, spending most of their time hunting. Those that emerge onto the surface of the snow and cannot regain their protected subnivean environment often die of hypothermia and starvation in a short time. They forage relentlessly in the subnivean world, hunting anything capable of supplying nutrients to their small bodies.

Small mammals are particularly vulnerable to cold as their size does not provide much protection. They MUST shelter in the snow cover. Voles, lemmings, deer mice, and shrews are active all winter, but mostly live entirely beneath the snow blanket. They build robust communal nests of grasses, lining the natal nests with hair plucked from their bellies for insulation. These are connected by meandering runs, sometimes several layers deep, helping them access fresh vegetation while remaining protected. Deer mice cache seeds and nuts, and then create nests beside the caches where they take shelter and can feed at leisure. Red squirrels open spruce and pine cones and remove the seeds, which they cache in middens against the base of larger trees. Snow covers the middens and provides insulation. The squirrels create entrances to these storage areas and can come and go up and down the trees, visiting the middens to feed and sometimes sleep, protected from the cold.

Even some larger mammals take advantage of the insulating qualities of snow. Snowshoe hares burrow into the softer snow at the base of trees, not living there full time but taking shelter in blizzards and during deep cold. They create short burrows under the snow to get access to the bark of willows and other vegetation, and feed under the protection of the snowpack.