IN 2017, Brandon Macdonald had a fateful encounter with a geo- logical engineer named George Gorzynski at a Vancouver coffee shop. Gorzynksi was the executive vice-president of Fireweed Zinc Corp., a junior mining company that he and a partner had founded in 2015. Fire- weed had just acquired a promising zinc-lead-silver property in the south- east Yukon and was looking for someone to assume the reins of CEO.

Macdonald, whose background includes working as an exploration ge- ologist, a mining camp manager, and a mining analyst, as well as a stint in investment banking, had been recommended to Gorzynski by his boss, Rob McLeod, the CEO of IDM Mining Ltd., a Vancouver-based gold development and exploration company.

Early in their chat, Gorzynski asked Macdonald if he happened to know anybody from Ross River, a predominantly First Nations com- munity of 300 people that is the closest settlement to Fireweed’s remote exploration site. Gorzynski was more than a little surprised when Mac- donald informed him that he was born and partially raised in Ross River. Macdonald’s parents moved there in the late 1960s to run an expediting company at a time when the region was hopping due to the development of the Faro mine.

Macdonald’s familiarity with the Yukon and the local community, coupled with his mining experience and financial literacy, land- ed him the post. Today, he can’t help but mar- vel at the synchronicity of it all. “This job has radically changed the trajectory of my career,” Macdonald says. “I would never have thought that having Ross River as my hometown would be a deciding factor in changing that trajectory because it’s such a random factor... On the face of it, it wouldn’t make a difference on any other project. So, it was a happy coincidence for sure. It seems that the stars were aligned for me on this.”

The bearded, 45-year-old CEO is seated at his desk high above downtown Vancouver with the blinds drawn to block the blazing afternoon sun. The compact room is patterned in basic grey and devoid of frills, much like Macdonald, who is dressed casually in a short sleeve shirt, stretchy trousers, and sneakers.

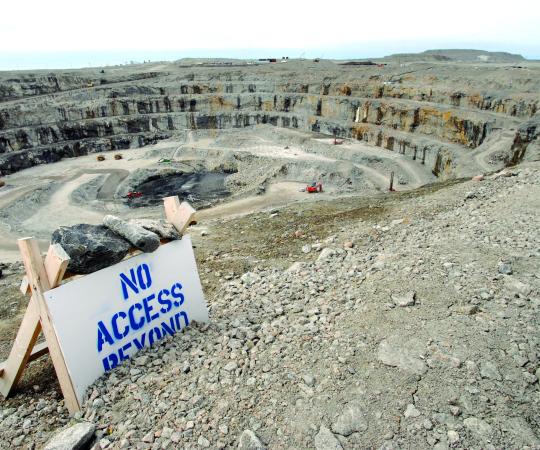

If the CEO cuts a casual figure, the Yukon project that fate has propelled into his orbit is anything but. Fireweed’s core property is a 940-square kilometre tract of land, accessible via airstrip and a three-kilometre road from the North Canol Road.

The parcel, known as the Macmillan Pass project, is home to four known zinc-lead depos- its and its development is essentially the story of Fireweed. The company’s origins involve the acquisition of two deposits—known as Jason and Tom—from Hudbay Minerals Inc. for a mere $1 million and a 16 per cent stock share in 2017, the year it launched on TSX Venture Exchange.

“Hudbay was looking to diversify into cop- per and had no real desire to set up operations there,” Macdonald says. “We saw what we call an ‘orphaned asset.” They had a project in their portfolio with no real intent to advance.” That first acquisition gave Fireweed a 54-square-ki- lometre parcel of land. A series of subsequent deals brought the Macmillan Pass project to its current district-scale—the first time the entire area has been assembled under one company.

Fireweed now owns all four known large zinc mineralized systems in the region—Tom, Jason, Boundary Zone, and End Zone—as well as many other zinc exploration targets, including the entire highly prospective “fertile corridor” that extends from Tom to Boundary Zone and beyond. More intriguing, only a small proportion of the vast land package has been explored using modern techniques.

Historical records for Tom and Jason show near-surface deposits with indicated resources of 6.4 million tonnes grading at 6.33 per cent zinc—a high grade— 5.05 per cent lead, and 56.55 grams per tonne silver. Four diamond drilling rigs were turning on the property through this fall’s drill program,

two at Boundary Zone, and two at Tom West. Nineteen drill holes were completed by mid-September, totalling 5,234 metres, while more than 8,315 metres of core were successfully scanned using state- of-the-art sensors. “All of the known depos- its are mineralized outcrops that are located near the surface,” Macdonald says. “The un- answered question is how many other depos- its are there that are 50 to 100 to 400 metres below that have no surface expression, that you need to find by geophysics or some type of advanced structural modelling?”

The Boundary Zone deposit also has significant thickness as well as a high grade. “There are intersections that are hundreds of metres thick. It makes mining significantly easier,” Macdonald says. “We have the po- tential to be one of the top 15 or 20 zinc and lead mines in the world, and new discoveries in Boundary and Boundary West could cata- pult us further up the chart.”

The Macdonald family moved to Victoria in 1982. The Yukon, however, was never far from Brandon’s mind. He returned each sum- mer to work with his father, who ran an outfit that handled the logistics for mining compa- nies, arranging the tents, the cookshacks, the fuel, and the supplies for the workers. Many of his co-workers were members of the local First Nations group. “Brandon’s father is a family friend of the chief,” Fireweed’s execu- tive chairman John Robins noted in a 2019 Northern Miner article. “Establishing a social licence is absolutely critical in a project like this. If you get off on the wrong foot and alien- ate the First Nations, you’re done.”

Despite that background, Macdonald didn’t go directly from mining camps to the executive suite. After earning a degree in geology from the University of British Columbia, there was a period of wandering. Feeling listless and unsure of his future in his late 20s, Macdonald applied for and was accepted into the MBA program at Oxford University. After graduating he took a job structuring project financings and invest- ments for the Macquarie Bank in London, England. He entered the field because he felt it would be an interesting change of pace. But he didn’t thrive there. “It’s a very competitive and ruthless world. You really need to have a thirst for the game that I didn’t have. I like doing my job well and succeeding, but I’m not a hustler.”

Macdonald returned to Canada and the mining realm, working in various roles, but pri- marily as a consultant. “I was never a principal with a company until Fireweed,” he admits. He also sharpened his hustle. Assembling that Yu- kon land package was only a start.

The drills have been turning at Macmil- lan Pass ever since, and Fireweed has been active on new fronts. In May 2022, the junior purchased the rights to a 12- square-kilometre parcel of land in the Northwest Territories’ Mackenzie Mountains that contains the critical metals zinc, gallium, and germanium, in addi- tion to lead and silver.

Situated 180 kilometres north of Macmil- lan, the Gayna River project was originally de- veloped in the 1970s by Rio Tinto. More than 28,000 metres of drilling outlined a large target with mineralization potential of approximately 51 million tonnes of five per cent combined zinc and lead. But Rio Tinto allowed its claims to lapse, believing there was low potential for a high-grade deposit. As a result, Fireweed was able to acquire 100 per cent of the Gayna River project at a modest cost by staking an area of 12,875 hectares.

“We staked a claim because there was a pa- per published that suggested there might be a deposit there of a type that Rio Tinto wasn’t looking for,” Macdonald explains. “Ivanhoe Mines has a zinc-copper deposit in the Congo that is unique for its high grade. The geological conditions there are very similar to what you see at Gayna River.” Fireweed’s approach here is similar to what the company is following at Macmillan Pass, building upon historic explo- ration by employing modern scientific tools and understanding to unlock a previously undiscov- ered mineralization.

As mineral exploration techniques and technologies continue to improve, the advances enable geologists to find things that might have been invisible to previous generations of ex- plorers. “Today’s geophysical surveys produce complex data sets which need computers to process,” Macdon ald says. “When Rio was exploring for zinc in the Gayna River in the 1970s, computers had a power that was a tiny fraction of your mobile phone, let alone a true server. We’re able to do machine learning now that allows us to massage that data and interpret it in ways that they couldn’t before.”

A month after the Gayna River transac- tion, Fireweed cut a deal with the Northwest Territories government to purchase a dor- mant tungsten mineral exploration project straddling the N.W.T.-Yukon border. The Mactung claim hosts an estimated 33 mil- lion metric tons of ore averaging 0.88 per- cent tungsten trioxide, making it one of the largest-known tungsten deposits outside of China, the main player in the market. The property was once owned by Vancouver- based North American Tungsten, but it was forced to shut down its operation in 2015 due to low commodity prices and heavy debts. The territorial government then stepped up to buy Mactung for $4.5 million.

The Mactung property was set to be sold in tandem with another mining property — the former Cantung mine, which the Cana- dian government has responsibility for, but Fireweed would only agree to buy the unde- veloped property. Under the signed agree- ment, Fireweed will pay as much as $15 mil- lion to the NWT government if the project advances to the mine decision stage.

Macdonald admits that Fireweed wasn’t shopping for a tungsten mine, but the prop- erty’s location, just 13 kilometres north of the Macmillan Pass project, was hard to resist.

“Our Tom deposit is closer to Mactung than it is to Boundary and both sites are accessed by the same road,” Macdonald says. “We have the potential to share the same power plant or the same power spur from the main grid. So, there’s a lot of synergy in terms of develop- ment. We also know there are concerns about cumulative effects. We believe you can handle this concern more effectively by having one proponent for each project. It allows you to do things that you can’t do with separate entities, like sharing an airstrip or sharing a camp or other types of infrastructure.”

Tungsten is used primarily for harden- ing steel for tools such as mining excavators. Since it has the highest melting point of any metal it is featured in the aerospace indus- try and certain electronics. It also has de- fence applications. The current demand for the metal, however, is tiny, less than one per- cent of the market for zinc, and there is not a single tungsten mine operating in North America. What makes its future value as a critical metal intriguing though, is that 85 per cent of the world’s tungsten supply comes from China. “This sort of monopoly makes a lot of western governments nervous to be so reliant on a government that they have an uneasy relationship with,” Macdonald says.

After adding the Gayna River and Mac- tung projects to its portfolio, Fireweed Zinc changed its name to Fireweed Metals, an in- dication it was moving into the field of criti- cal metals. A critical mineral is defined as a metallic or non-metallic element that has two characteristics: it is essential for the function- ing of modern technologies, economies or national security and there is a risk that its supply chains could be disrupted.

“With zinc and tungsten now designated as critical minerals by Canada, the U.S. and the EU, Fireweed is positioned to be a significant critical min- erals player on the world stage and help enable the transition to a sustainable low- carbon economy,” Macdonald says.

Even so, he stresses that the company’s major focus is still its flagship property at Macmillan Pass. “We’re following the path to develop a mine. Our intent is to de-risk it and obtain permitting and go on to construction and operation. If along the way someone wants to team up with us or purchase us, we are certainly willing to entertain it.”

Macdonald finds his job as CEO of a junior mining company to be all-consuming. He works long hours, and they start early. “This job takes a lot out of you. The first thing I do in the morning, before I even get out of bed, is check my phone to see if there are any emails that necessitate me responding immediately because we are dealing with so many different time zones. As the CEO of a public company, you often feel like your share price is your re- port card and that the grade on the card is constantly being updated every minute over the course of the work week.”

Despite the demands. Macdonald is primed for the challenge. “This is my first time in the big chair, but I find that I really enjoy this. I have worked for bigger companies but I’m more com- fortable in a small company. I’ve always said that I would rather be the head of a chicken than the tail of a bull. In this setting, I feel that I am more the master of my own destiny.”