WHEN I ASK A FRIEND WHO LIVED IN YELLOWKNIFE for many years about wood bison, his recollections all involve driving: a first sighting in the gloaming of a late-summer evening in 1989, naught but a dark outline and two glowing retina by the side of the road; regular highway cruises to spot them after the NWT government cleared roadside forest for safety reasons in the early 1990s, creating a subsidized, all-you-can-graze buffet for bison; taking his visiting mother on one tour and seeing so many of the shaggy, hulking creatures that spotting a porcupine was a surprise. “Bison are the second-best sight in the NWT after the northern lights,” my friend enthused. “It just never gets old.”

For bison, roads mean ease of movement, the pleasure of mowing verges to scrub, even snoozing on the pavement while the wind keeps the flies at bay. As with their smaller plains-dwelling cousins in places such as Yellowstone National Park, these uncanny creatures are obstinate and unmoving because they can be. And while drivers on Highway 3 between Fort Providence and Yellowknife experience similar bison-related slowdowns to those at Yellowstone, at least there are no carnival-like traffic jams caused by naïfs attempting dangerous selfies with creatures whose males can stand two metres at the shoulder and weigh close to a tonne. Still, seeing North America’s largest land animal—a remnant of Pleistocene megafauna that once included mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses—is a symbolic welcome for visitors to the North, where it often seems the last ice age has only recently departed.

Given their predilection for thoroughfares, collisions are inevitable. That adds yet another challenge to a species at risk already reduced to small, widely separated populations also facing threats from disease, genetic stagnation, climate change and dwindling habitat. The Nordquist herd, for example, habituated to a stretch of the Alaska Highway straddling the B.C.-Yukon border, conservatively loses an estimated one in every five members to vehicle collision—a 20-per-cent attrition rate well in excess of the long-term annual average of just more than half a per cent for the NWT’s most traffic-involved population.

Long-standing conservation efforts have wrested from the brink this animal that can shape its own habitat and that of other species. And because bison also have both cultural and sustenance value to many (more than a dozen different names exist for bison in NWT Indigenous languages), their loss from the landscape would rupture both ecological and community connections. But large population fluctuations raise concerns over the long-term stability of bison in the NWT among wildlife managers, communities and people who enjoy seeing them from the comfort of a car—or would like to.

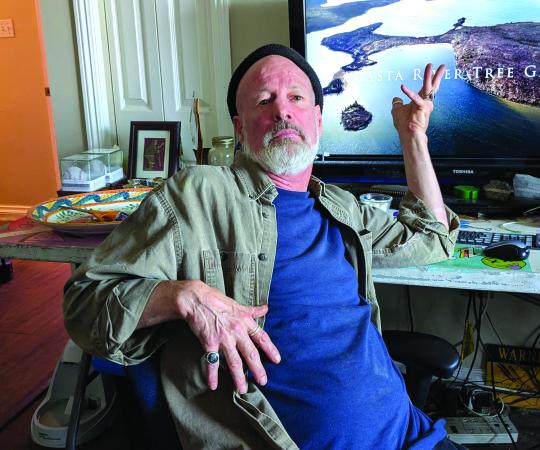

Photo courtesy of Colin Field/NWTT

Photo courtesy of Colin Field/NWTT

WHAT USUALLY STRIKES people first about bison is how big they are. “It isn’t clear until you’re close that they’re absolutely huge,” says Terry Armstrong, a veteran bison ecologist for the NWT government. Working with animals that are so much larger and more powerful than other wildlife requires special caution. “You need a different mindset,” he says. “They look docile when they’re lying around chewing cud—kind of like wild, furry cattle—but they’re far more agile and can be running at full speed in an instant.”

Yet wood bison impress with more than mere size; their entire mien screams biodiversity icon. Dark brown to near black, the enormous head, prominent shoulder hump and forelegs host a characteristic mane of soft hair. Both genders feature short, dark horns, males’ curving inward. Bison are considered ecosystem engineers because their grazing and bioturbation (churning of the soil with their hooves or the “herd effect”) benefits plants and creates trails and wallows used by other wildlife. As the largest herbivore on the landscape, they also cycle a significant amount of nutrients through their droppings and when they’re predated or scavenged.

Denizens of the boreal forest, wood bison once ranged over half of northern British Columbia, all of northern Alberta into western Saskatchewan and a vast swath of Alaska, Yukon and the NWT to the Arctic Coast. Combined with the stress of habitat shifts and severe winters in the 1800s, profligate hunting drove them to the edge of extinction, their numbers plummeting from about 168,000 in the early part of the century to a few hundred by its close. Indeed, the species persists in Canada only by dint of isolated reintroductions now comprising nine free-ranging populations, several of which cross provincial or territorial borders. The Yukon’s only full-time population is the Aishihik, while three call the NWT home: the Nahanni, Mackenzie and Slave River Lowlands populations—the latter a subset of the Greater Wood Buffalo metapopulation (several herds that interact with each other) shared with the eponymous national park and Alberta.

This “pittance” of its historic range—as Yukon senior wildlife biologist Thomas Jung calls it—along with relatively small populations, ongoing declines and other threats, led to the species’ listing as threatened under species-at-risk legislation in both the NWT (2016) and Canada (2018). Management of NWT populations is guided by a 2019 recovery strategy developed by the Conference of Management Authorities (CMA) in partnership with the Tłı̨chǫ Government, wildlife and resource management boards and community stakeholders. The CMA’s Progress Report on the Recovery of Wood Bison in the Northwest Territories (2020-2024), released in April, makes the challenges of conservation initiatives clear. That starts with the need for individual strategies to cover each population, whose geographic separation means several things, including variable food sources in differing habitats. Though bison are generalists that mostly graze on whatever is freshest and most nutritious—usually grasses, sedges or forbs—they may also nibble on lichen in fall or browse young willow in summer. “But even then, only in some places,” Armstrong says, “like along the Liard River where there’s heavy new growth on sandbars every year.”

Another reason for bespoke recovery strategies relates to each population’s unique origin and the effect this has had on both its genetic and general health. The history of the Greater Wood Buffalo metapopulation, for example—which includes the Slave River Lowlands’ herds—is fraught. One of Canada’s last outposts for wood bison, whose numbers bottomed out to fewer than 250 in 1896, the population rebounded over the next two decades.

After the 1922 creation of Wood Buffalo National Park (WBNP) to protect habitat and prevent backtracking toward extinction, almost 6,700 plains bison from Alberta were introduced to mix with their wood-dwelling cousins. These reinforcements and ensuing crossbreeding resulted in a high of about 12,000 bison roaming the park by 1934 and a welcome increase in genetic diversity that persists to this day.

Of the NWT’s three populations, long-term fluctuations are greatest in the Slave River Lowlands. Bison disappeared from this area in the late 1800s only to recolonize in the 1940s. Thriving in lush sedge meadows, they reached about 1,700 by the 1970s before decades of see-sawing; numbers had returned to early-’70s levels by 2009 only to plunge again to some 256 animals in 2024.

Bison movement between the NWT, Alberta and WBNP could play a role, but biologists aren’t sure what caused these wild swings. “A number of potential factors come to mind, but we don’t know which are dominant and which are less important,” says Armstrong. “And in my opinion, the bigger the animal, the harder that is.”

The Mackenzie population represents the first reestablished from scratch. In 1963, 16 animals from an isolated corner of WBNP were released into the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary, a new protected wildlife reserve of over 10,000 square kilometres stretching south to Great Slave Lake from Highway 3 between Fort Providence and Behchokǫ̀.

By 1989, the population had increased to about 2,400 before a slow decline began, accelerating in a 2012 anthrax outbreak. It now appears to be on the rebound, extending its range both eastward toward Yellowknife on Highway 3 and northward on Highway 9.

The success of the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary inspired the release of 40 wood bison from Alberta’s Elk Island National Park near Nahanni Butte in the 1980s and then another 59 north of Fort Liard in 1998. Though this Nahanni population now ranges throughout the Liard River Valley, its 2021 estimate of 544 animals is just more than half the 2017 count.

These numbers represent critical knowledge because reliable census of bison, which require both population estimates and classification counts (bull, cow, yearling, calf) isn’t easy. “WBNP is larger than some countries at 44,741 square kilometres, making comprehensive surveys time-consuming, costly and labour-intensive,” says Pinette Robinson, bison project manager for Parks Canada, whose population estimates date to the 1940s with classification counts added in the 1970s. Even with support from community members and multiple planes flying, it can take several weeks to survey the entire park.

Classification counts once involved dropping biologists on the ground to ogle herds with binoculars. But new technology and the bison habit of spending time in the open mean these can now be done by air. “We have a pretty good camera and can fly around herds photographing, then go back to the office where a tech sorts through the shots,” says Armstrong, who also enthuses over GPS collars whose continuous location feed can aid counts, help identify herd affiliations, provide conflict-related information such as time spent on roads or in communities and track habitat usage.

After the 2023 WBNP wildfires, aerial surveys, observations and GPS-collar data showed no evidence of fire-related mortality. Indeed, bison returned to burned areas only weeks after the fires—open landscapes that now facilitated movement and new vegetation. “Recent surveys show healthy calf numbers and stable population trends,” says Robinson, “suggesting wildfires may have

had a neutral or even beneficial effect on herds.”

Still, though the bison roller-coaster remains hard to decipher let alone stabilize, at least one contributing threat is clear: pathogens that can make animals vulnerable to everything else.

Photo by Peter Mather

THREE BACTERIAL DISEASES hinder the management of wood bison: bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis, both derived from cattle, and naturally occurring anthrax. The Wood Buffalo metapopulation became infected with the former two through the plains bison introduction in the 1920s. Although both are now endemic in the Slave River Lowlands and adjacent subpopulations, communities in these areas support the presence of bison despite the challenges posed to both management and harvesting.

While infected bison can experience lower winter survival, reduced breeding success and increased susceptibility to predation, direct mortality is low. Advanced tuberculosis causes only four to six per cent annual mortality in WBNP. Part of this may have to do with infection rates. In the ’80s and ’90s, 25 to 31 per cent of WBNP bison were positive for brucellosis and 21 to 49 per cent for tuberculosis, suggesting that, even within affected herds, a significant portion of animals remains disease-free.

Nevertheless, chronic diseases are most certainly detrimental, resulting in extensive efforts to contain them. Since 1987, a Bison Control Area—basically a large, bison-free buffer zone—has reduced the risk of disease spreading from the Wood Buffalo metapopulation to the disease-free Mackenzie and Nahanni populations. Unfortunately, wildlife personnel destroy any bison found in the control area and test them for disease. All three animals removed in 2024 tested negative.

The third affliction, anthrax, is more notorious due to its acute nature, high mortality rate and greater risk to humans. Bison and other ungulates are exposed to anthrax spores through wallowing and feeding. The NWT’s Environment and Climate Change department, which manages outbreaks in the Slave River Lowlands and Mackenzie populations, conducts routine aerial anthrax surveillance—essentially a search for carcasses—from June through August each year; Parks Canada manages anthrax in WBNP.

Outbreaks occurred in the Slave River Lowlands in 2023 and WBNP in 2022–2023, but anthrax hasn’t been reported in the Mackenzie population since the 2012 outbreak and never detected in the Nahanni population. The Anthrax Emergency Response Plan, triggered in 2023 for the Slave River Lowlands outbreak, works to minimize release of anthrax spores into the soil and protect both bison and public health through monitoring, reporting and carcass disposal.

Though it has so far proved useful, the Bison Control Area and other disease-management actions continue to limit species recovery. For instance, if they weren’t disease vectors, individuals from the genetically diverse Wood Buffalo metapopulation could be used as breeding stock to augment the low genetic diversity of disease-free populations. Help on that front, however, may be on the way.

In 2022, Genome Canada announced $5.1 million to fund the Bison Integrated Genomics project, a national, multi-agency

effort involving the innovative use of genomic sequencing. The primary objectives are: the development of diagnostic field tools to detect brucellosis and tuberculosis; a wood bison vaccine for both diseases; means to rapidly identify genetic composition of bison herds; and the ability to transfer disease-free eggs and sperm among wood bison populations to ensure greater genetic diversity.

Armstrong, who works with the group, believes the prospects for achieving these goals are “reasonably good—but over the long term, possibly decades.”

The objectives of the project closely fit with the government’s goal of recovering broadly distributed, free-ranging, genetically diverse and healthy wood bison populations that can sustain ongoing harvest. Scientists will know that this strategy is working when the populations increase or stabilize, the herd distribution expands, the at-risk status improves and more communities support management objectives.

Oh, and probably if there’s less roadkill. Despite awareness campaigns designed to reduce collisions and human-bison conflicts, biologists worry that more bison will die by car. About 89 per cent of the NWT’s long-term average of 12 collisions per year involve the Mackenzie population, whose range is creeping toward Yellowknife’s higher speeds, volume of traffic and increased highway maintenance, increasing risk for both people and bison.

It’s not hard to understand the latter’s affinity for asphalt—roadside plants provide excellent forage. As a result, they use adjacent areas for feeding, wallowing and, sometimes, even calving. Is there an irony in a species at risk developing an attraction to one of our most deadly creations?

Of course. Which is why the efforts to ensure roads don’t become a major threat to wood bison recovery are so important. But Armstrong doesn’t believe it’s realistic or even desirable to expect individual populations not to fluctuate—as long as the numbers across the animal’s range remain stable or increase. “The boreal forest is a very dynamic ecosystem,” he says. “But when it comes to bison, the reality is we don’t know what’s normal.”