Mark Brown’s weathered face lights up as he clutches a baseball-sized chunk of grey-brown granite. It’s an ordinary rock known as Acasta gneiss, and Brown, a frail man, admits it isn’t much to look at. But he sees more than the stone in his hand. Until recently, Acasta gneiss (pronounced “nice”) was believed to be the planet’s oldest known rock. Since 2015, Brown’s generated a steady income from selling samples in polished spheres and silver jewelry to rockhounds, collectors and scientists worldwide. But he sees much more than a curio.

“When you put this rock in your hand and I tell you it’s the oldest, what do you ask?” Brown says. The answer to the obvious question—the rock’s age—is 4.031 billion years, only a billion or so years after the Big Bang created the universe. Brown, however, has a bigger question. “It’s important to know where you came from, as a human person on this little blue planet, floating around on the cosmos. You think, ‘Oh, I’ll have a coffee at the Gold Range.’ But where are you from?”

Honestly, it’s easier to ask where the rock comes from. It’s named for the Acasta River, located about 300 kilometres north of Yellowknife, where local prospectors Walt Humphries and Brian Weir discovered an outcrop in the 1980s.

Since then, Yellowknife has claimed a small bragging right that’s often shared with visitors and in tourism guides. In June, however, a team of academic geochronologists reported finding a 4.16-billion-year-old basalt in Nunavik—129 million years older than Acasta.

That’s a blip on the geological timescale, but it’s enough to undermine the NWT’s claim as home to the oldest rock on Earth. The stakes are probably higher for Brown, who built a career as a driller’s helper in exploration camps across the Arctic. He’s paid a price for decades of hoisting drill steel and core boxes with painful shoulder and spinal injuries that ended a career he loved. But the Acasta story put him on a different path.

Thinking that selling this odd, old rock could augment his modest disability allowance, he scraped together enough money to stake an adjoining claim and harvest a few hundred kilograms. Knowing little about geology and even less about marketing, he then sought professional guidance and created his Rock of Ages brand to take his vision to the world.

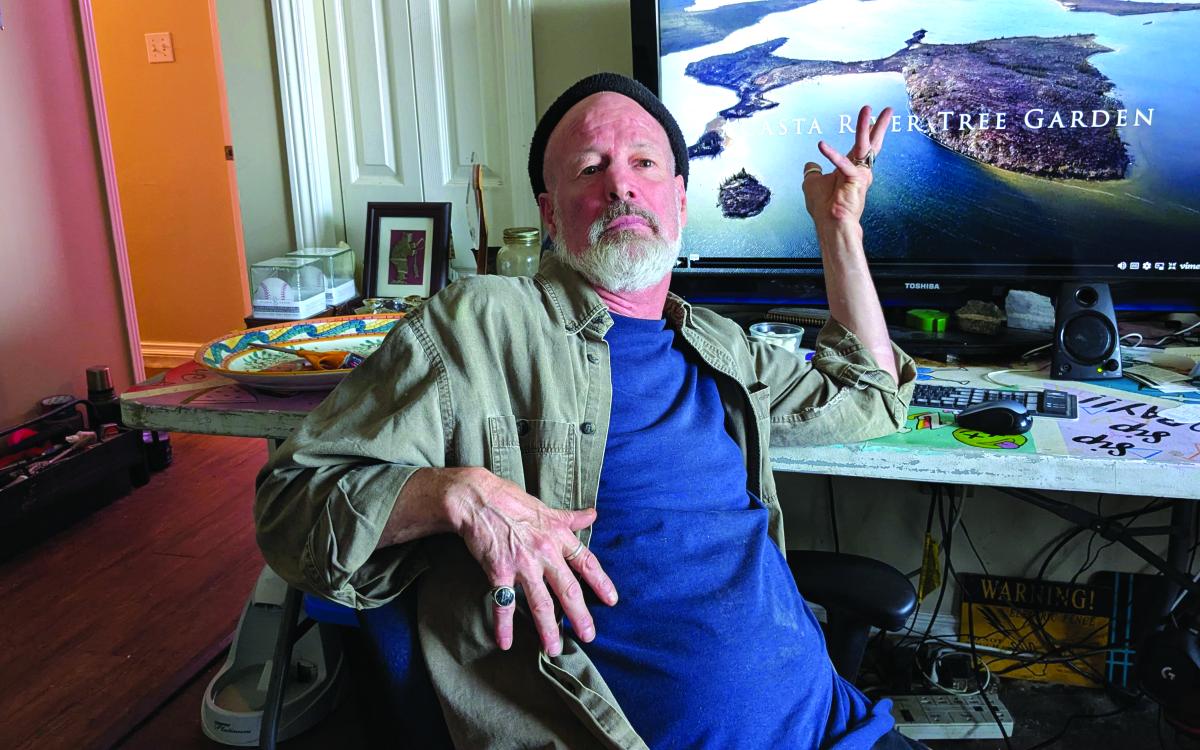

Photo by Bill Braden

“My whole heart, my whole mind is all about this,” says Brown, who lives with his cat, Cookie, in a fourth-floor walkup cluttered with rock samples, claim maps and the “Captain’s Chair,” a wheelchair that helps him endure his injuries. “I’ve sold thousands of items and specimens around the world… I can’t sell second-best.”

Business is only part of the blow to Brown. Acasta gneiss has created the world he now inhabits. It introduced him to ecologist David Suzuki and astronaut Chris Hadfield. It landed him on the front page of the Globe and Mail and on the CBC’s Dragons’ Den. The story so impressed the Smithsonian Institution that it hauled a 3.5-tonne sample to Washington, D.C., and put it on display.

Most of all, it stirred his sense of wonder. “What we’re talking here is the metaphysical,” Brown says. “We’re talking spiritual in comparison to the geological.”

Geology, in fact, may come to his rescue. Scientists used different testing methods to determine the ages of the Acasta gneiss and the Nunavik basalt. Brown holds on to a hope that a consistent dating method for both rocks may preserve the faith he’s put into the Acasta gneiss.

“I am the voice of the rock,” he says. “Where did it come from? God? The Creator? Whoever your spiritual person is, think about that… You are holding the origin of planet Earth. Now how freakin’ cool is that?”