We were teenagers.

It was 1968 and fresh from surviving the dismal and stifling Grollier Hall in Inuvik we found ourselves at Grandin College in Fort Smith.

Set on the banks of the Slave River, the high school residence was a breath of redemptive air. True, Grandin was still run by the same Catholic Church that was trying to commit cultural genocide in government-approved institutions of ‘learning’ across the country. But our director, father Jean Pochat, took a brave step away from the church’s colonial mission. The church wanted him to turn out priests and nuns. Pochat knew we needed leaders.

At Grandin, the assembled Dene, Métis, and Inuvialuit students were made to feel like we mattered. We could wear our hair long. We could speak our own language. We were treated like human beings and told we could actually aspire to serve the North in a meaningful way. Across our different cultures we communicated with each other like family. Out of the seeds that were planted in Grandin came future premiers, politicians, Dene Nation chiefs, and us—an author and a filmmaker.

Father Pochat would often invite exceptional people passing through town to come speak with us students, and that’s how we came to hear the message of George Manuel. We had no idea who the heck he was when Manuel showed up to an assembled Grandin student body. First impressions were not too encouraging. He was short, with a pot belly and a homely face with glasses, but a winning smile.

Manuel, who later went on to lead the National Indian Brotherhood, talked about organizing native people in British Columbia, of the great challenges of breaking the chains of colonialism that kept our people poor and impoverished.

He talked about the racism that our tribes endured in our one-sided relationship with Canada. He looked us in the eye and told us that we, the newly educated youth, needed to work together to reclaim our lands, our language, our culture. With the wisdom and experience of our Elders, combined with our new skills, we made a formidable team.

Our people were on the cusp of a new relationship with Canada. We were the first generation who ‘came out of the bush’ and went to the white man’s schools. We were a generation who could read the treaties our ancestors had been coerced to sign, and challenge them in the courts with our writing. We could take control of our destiny.

The late 1960s was a time for this kind of great change. All over the world there were new sounds, new art, new politics, and new ideas. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, bell-bottom jeans, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, second-wave feminism, Mohammed Ali, Bobby Orr, the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., and the incandescent American Indian Movement. A cultural revolution was taking place. And the North was no exception.

On October 3, 1969, 16 chiefs came together as the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories. The organization was officially incorporated the following year. Over the past 50 years we’ve watched as the Indian Brotherhood grew from its humble beginning, fighting against the exploitation of our lands, to a powerful voice known today worldwide as the Dene Nation.

It was the first time native peoples in Canada stood together and said, ‘No.’ The church, government, and corporations had controlled our lives. They tried to silence us. They tried to fracture us. Instead, we united.

The Dene Nation did for Dene people what George Manuel and father Pochat did for us kids at Grandin. It created the tools to let Dene determine their own future.

We were only a scraggly bunch of rebels back then, living paycheque to paycheque, trying to protect what was ours. Scrappy, crazy kids who knew we were on the right side of justice. But the spark of political awareness had been lit. It was up to each of us to speak out.

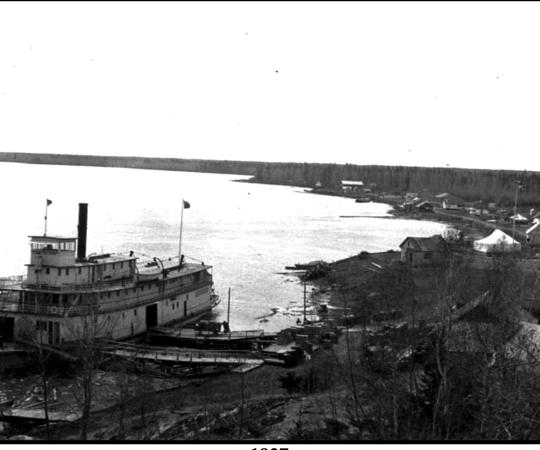

One hundred years ago Imperial Oil arrived uninvited and unannounced in the North. The company came to the NWT with a lust to pull oil from the ground, but no room in those plans for the Dene living on the land. Imperial went as far as occupying three traditional log homes, forcing out the Dene families who’d been living there. The company was “choking us, little by little,” as Joe Blondin, Raymond’s grandfather, once remarked.

It was always about the land, and what the land contained—oil, gold, minerals. Our value to Canada was always weighed against whether we could help or hinder this hunger to exploit our home. The roots of modern colonialism dig deep.

In 1897, gold was found in the Yukon River. The next year, mineral claims were first staked at Pine Point. In 1899, Treaty 8 was signed between the Crown and Dene of the South Slave to clear the way for ‘development.’

When oil was discovered in 1911 around Norman Wells (in an area then known as Fort Norman), it was Catholic bishop Breynat who shipped the first samples down to Edmonton. It was the same year the 60th parallel became the territory’s southern border.

In 1921, the Crown signed Treaty 11 with Dene living north of Great Slave Lake, setting up a still-disputed land transfer and the path to more resource extraction. Before the people who’d lived here for generations realized what was happening, claims from outsiders were being staked to the mineral-rich country under their feet.

“[The signees] wanted the best for the people on their own lands. This was their hope,” says Violet Camsell, a longtime Dene Nation observer from the Tłı̨chǫ and co-founder of the Native Press. “The Government of Canada had different ideas of what signing the Treaty meant.”

It’s unlikely many knew what they were signing. The church and the oil executives and the Crown came with empty promises and deceitful smiles. When you look at individual copies of the signed treaties, they clearly show a single hand marking hundreds of “Xs” signifying Indigenous consent. The same way you’d mark a BINGO card, hoping for the best. At the time Treaty 11 was being signed, oil drills at Norman Wells had already been tapped, ready to start production as soon as the ink dried.

These men enriched themselves to lavish degrees on what they took from our lands. But it still wasn’t enough. They needed to extinguish us.

In 1969, the original Prime Minister Trudeau and Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chretien brought forth the infamous White Paper. Among other policies, the paper called for the abolishment of the protected “Indian” status. Ottawa wanted to wash its hands of a constitutional obligation to Indigenous nations. The Indian Act was racist, yet at least acknowledged our identity. This was identity theft on a national scale.

“The objective was to assimilate Indians, to make them become part of the Canadian society,” Françoise Paulette, Dene leader and co-founder of the Indian Brotherhood of the NWT, said in his biography. “Forget your past, forget your drums, forget your life. That was the turning point for Indigenous people in Canada and I was just 19 years old.”

In these politically perilous times, 16 chiefs, a staff of 25 Indian Brotherhood workers, and 7,000-plus Dene voices mobilized for battle.

Before the Indian Brotherhood, it was difficult to organize. Travel for meetings was expensive. Many didn’t have the awareness or education to understand the decisions being made about their lives in Ottawa’s boardrooms and courthouses. That changed as mass communication came north. Through the Native Press

and its radio broadcasts, as well as years of community-based workshops, the Indian Brotherhood helped bridge the geographical divide.

Meanwhile, educated Dene returned from southern schools ready to put their credentials and street-savvy into play. We were maddened bulls, tortured and maligned, who could only see red. We were the children who had routinely been strapped for daring to speak our language and called savages. One thing you could say the doomed White Paper produced was a great number of Indigenous lawyers ready for a fight.

Our focus was the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline. At stake was a gas pipeline from the Arctic Coast to refineries in the south, cutting through the very heart of Dene lands.

In 1973, Chief Paulette and the rest of the Indian Brotherhood took on the daunting legal task of challenging Treaties 8 and 11, arguing that Dene still held a legal title—a caveat—over the Crown lands of the Mackenzie Valley. Justice William Morrow presided over hearings that introduced case law going all the way back to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, when the British Crown issued a protection of Indigenous lands. Elders, like 90-year-old Julian Yendo of Fort Wrigley, testified that they clearly remembered the original signing of those documents as friendship treaties, and not a transfer of property.

It was a momentous day when Morrow affirmed that, yes, Dene had been coerced into signing. We had never surrendered the rights to our territory, and thus still had caveat over our homelands.

The Supreme Court of Canada would eventually overturn the ruling on appeal by the federal government, but Morrow’s findings on Indigenous rights remained and the Paulette Caveat, as it is now known, prompted Canada to hold public hearings on its pipeline. The Berger Inquiry, presided over by Justice Thomas Berger, heard from Dene, Métis, and Inuvialuit in more than 30 northern communities before concluding, in 1977, with a decision to delay pipeline construction until land claims could be settled.

The years of battles in and out of court put all of our collective energies to the test. The pipeline was a polarizing topic throughout the North, making for a fair share of testy confrontations between Dene and white people. Tensions ran high. We were all under investigation by the RCMP. The Indian Brotherhood office above Harold Glick’s menswear Tog Shop was broken into several times. But we had each other.

Interpreters like Jim Sittichinli, Joe Tobie and Louie Blondin translated the English hearings for CBC so all Dene could listen to what was at stake. There was Herb Norwegian, Jim and Gerry Antoine, and Chief Frank T’Seleie, then only 25, who during the hearings in Fort Good Hope called Foothills Pipelines president Bob Blair a “20th Century General Custer.” They were willing to die for their rights. Some did. Ed Bird, our vice-president, was shot by RCMP in his own home and died in an Edmonton hospital.

This was at a time when many Dene still lived on the land. Many on the Brotherhood’s staff were born on the land. We wanted to protect the pristine northlands we knew of as mother. This attachment to Mother Earth is an abiding one. It made this a fight for our lives. Canada, meanwhile, wanted to honour the spirit of its “Fathers of Confederation.”

A century earlier, in 1864, 23 white men arrived at a conference in Charlottetown, PEI, to invent Canada. By contrast, at the Dene Assembly in Fort Simpson in 1975, more than 300 delegates from all Denendeh communities gathered to discuss a draft version of the Dene Declaration. This was to be our people’s constitution. It was the first time in living memory where we asserted our Dene identity, our “Deneness” to the world.

“We, the Dene of the Northwest Territories, insist on the right to be regarded by ourselves and the world as a nation,” the declaration reads.

That night, when the caribou-skin drums came out, we danced with purpose and joy for our people and all of our Elders and the spirits who came before us. They were smiling down on us.

Georges Erasmus, one of the writers of the declaration, who would go on to become chief of the Dene Nation and the first Dene to become national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, says passing that document was a significant milestone.

“We were fighting all the shackles of colonialism imposed upon us and trying to find our rightful place in our country which did not respect and listen to us... It was a real honour and privilege to serve our people—to put forth our worldview, our values, and principles, which had always served our people well in the past and would do so in the future.”

For the first time we thought of ourselves as a distinct people in the Canadian Constitution. We weren’t Cree. We weren’t Inuit. We were Dene. When the Dene Declaration was published the following year, it loudly said to the whole country, “This is who we are.”

The victories were monumental, but there were also great losses. The failure to negotiate a comprehensive land claim in the ’80s caused a massive shift in the Dene Nation’s identity.

For nearly a decade the Dene Nation had been negotiating with the federal government for a comprehensive agreement that would cover all Dene lands in the NWT. A final version of that agreement was close to passing in 1990, but fell apart after a contentious vote at a joint Dene/Métis Assembly.

After that, Canada said it would only negotiate with the regional governments. Soon after the Gwich’in and Sahtu regions broke away to sign their own land agreements. The Tłı̨chǫ were the next to take control of their resources and future. Only the Akaitcho and Dehcho have yet to sign a land-use agreement.

The regional governments could clearly stand up and speak for themselves. So what was left for the Dene Nation to do?

“It’s been largely decapitated,” Stephen Kakfwi, former Dene Nation chief told CBC in 2018. “Two, now three regions, have no need for it. The Dene Nation has basically done nothing since 1987.”

It was also in 2018 that Norman Yakeleya (Raymond’s brother) was elected as national chief of the Dene Nation. Taking over from longtime leader Bill Erasmus, Yakeleya was the first new national chief in 30 years, and he campaigned on a platform of rebuilding and refocusing the waning Dene Nation.

“Right now, we have some strong local and regional governments but we are still too fragmented and uncoordinated as a collective,” he says. “This leaves us at the mercy of both the territorial and the federal governments.”

The Dene Nation has largely moved from political activism to cultural advocacy over the last couple of decades, but it can still speak for Dene globally, says Yakeleya. All Dene, in the NWT and across the world.

We are the largest First Nation on North American soil in terms of both population and land. There are 80 odd tribes stretching from Alaska to Mexico, all facing a similar loss of language, culture, and a fight for their homes. There are Dene in California, Washington state, and Alaska, in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, the Yukon, and even in Siberia.

The first International Dene Gathering was held in Calgary by the Tsuu T’ina Nation in 2004. Thirteen tribes answered the call. There was a feeling of family at the event. We knew we were with our lost relatives. Now, we could see and talk to each other. On the last day of the gathering, when it was time to say goodbye, the Elders cried and hugged each other as they knew they might never see each other again. It was a sad and proud moment, but told us we had much more work to do in bringing our people together.

The Dene Nation can be that beacon, calling out to Dene across the world. It can act as a watchdog, uniting our voices to remind local and international governments about the promises they agreed to. Just like the original Indian Brotherhood of the NWT did back in 1969.

Outside of our territory, we can go to Washington, D.C., or the United Nations to defend our lands from mineral exploration. Inside our Dene borders, such a singular authoritative voice isn’t needed anymore. The regions and communities are now more empowered to speak for themselves.

Perhaps, that is the Dene Nation’s ultimate legacy—autonomy for its people.

Back in Grandin College in the late ’60s, Raymond Yakeleya was just a normal student. He played hockey and joined the photography club. After graduation, he started working for Imperial Oil in Norman Wells—the same company that evicted his family from their homes in the ’20s and stole the oil under their land. But he always kept an eye and an ear on what was going on with the Dene Nation. It was during a 1975 public hearing in Norman Wells that he stood up and very publicly quit his job. It was his turn to fight.

For some, the Dene Nation was a path to political action—the legal battles to secure basic rights stolen from Dene communities. But the impact of the Dene Nation, and the rebellious era it came from, also had subtler effects. After quitting his oil job, Raymond didn’t get involved in politics or activism. He went back to school to learn photography. He discovered filmmaking at the Banff School of Fine Arts and University of Southern California’s School of Cinema. He became the first Dene filmmaker, ever. With that knowledge, he’s made a career as a documentary director, telling our stories, for our people.

From national legal battles to one man’s career in film, it all started from the same spark. It all comes from Dene wanting to speak for themselves. And that is why the organization’s spirit will never die, according to former Dene Nation vice-president Herb Norwegian.

“They will never take over our rights and take away our children again,” he says. “We must be like our Elders in spirit. Keeping our moccasins on the ground will keep us powerful as we go into the future… Stand firm on land and water and this will take us to the stars.”

Fifty years is not a long time. The relatively short journey of our people over these past five decades is one from a free life of hunting, trapping and fishing on our vast country to a sedentary change and more urban lifestyle. Like most of the Indigenous world, we’ve somehow shown the resiliency to keep, nurture, and carry forth our Indigenous traditions even as others sought to wipe them out. We changed the image of Dene in the world. We’ve inspired hearts and minds. We fought for, and won, the rights to our land.

Auntie Julie Lennie of Tulít’a once said that Dene lands are our life, and our life is our land. “If you would know our land, you would know our life. If you would know our life, you would know our land.”

The Dene Nation inspired a scraggly bunch of rebels in the ’60s to protect that life and that land. Hopefully, the next generation will be inspired to continue our fight.

The authors would like to thank Billy, Georges, François, Ted, Violet, Herb, Norman, Gerry, and all those who shared their memories with us for this story. This is a tribute to former chiefs, leaders, workers of the Dene Nation, and those, like father Pochat, who fought for our people—those who we need to honour. The list is very long but we all know who they are. Mahsi.