IN 1930, Philip and Jean Godsell left the North for a well-earned early retirement in Calgary. Philip held the lofty position of inspector for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s western district. Often accompanied by his wife, he travelled extensively throughout the Mackenzie Valley and the western Arctic islands, auditing account records at trading posts. Philip had a reputation for digging deep and uncovering inconsistencies and sometimes fraud. His work got a lot of employees fired and brought the struggling fur trade operations of the company back from the brink of bankruptcy.

Jean developed a reputation that was very different from her husband’s. In isolated fur trade posts throughout the North, while Philip was poring over accounts, Jean was busy making friends, and a few enemies, among the female population.

Jean Walker was born in 1895 in Glasgow, Scotland. At age 11, her family moved to Canada and settled in Winnipeg, where the Hudson’s Bay Company ran its network of fur trading posts and department stores in western and northern Canada. Jean joined the company in 1919 as a secretary and was soon brushing shoulders with many of the seasoned veterans of isolated northern fur trading posts. That’s when she met Philip Godsell, who was well on his way to becoming one of those seasoned veterans whose tales Jean found so fascinating. After a brief courtship, Philip proposed marriage.

Jean and Philip were married in the autumn of 1921 and immediately packed their bags and headed north. Philip’s work was headquartered at Fort Fitzgerald, and the only way to get there was by train to Fort McMurray and then by boat on the Slave River, which was beginning to freeze over. There was no time for a honeymoon.

Fort Fitzgerald sits in northern Alberta, a short distance south of the boundary with the NWT and the community of Fort Smith. The two communities are separated by major rapids, which are the only substantial barrier to river navigation over thousands of kilometres to the Arctic coast. The portage between Fort Fitzgerald and Fort Smith is long and difficult. In the 1920s, it was the only way to carry freight into the North and the only way to bring furs out.

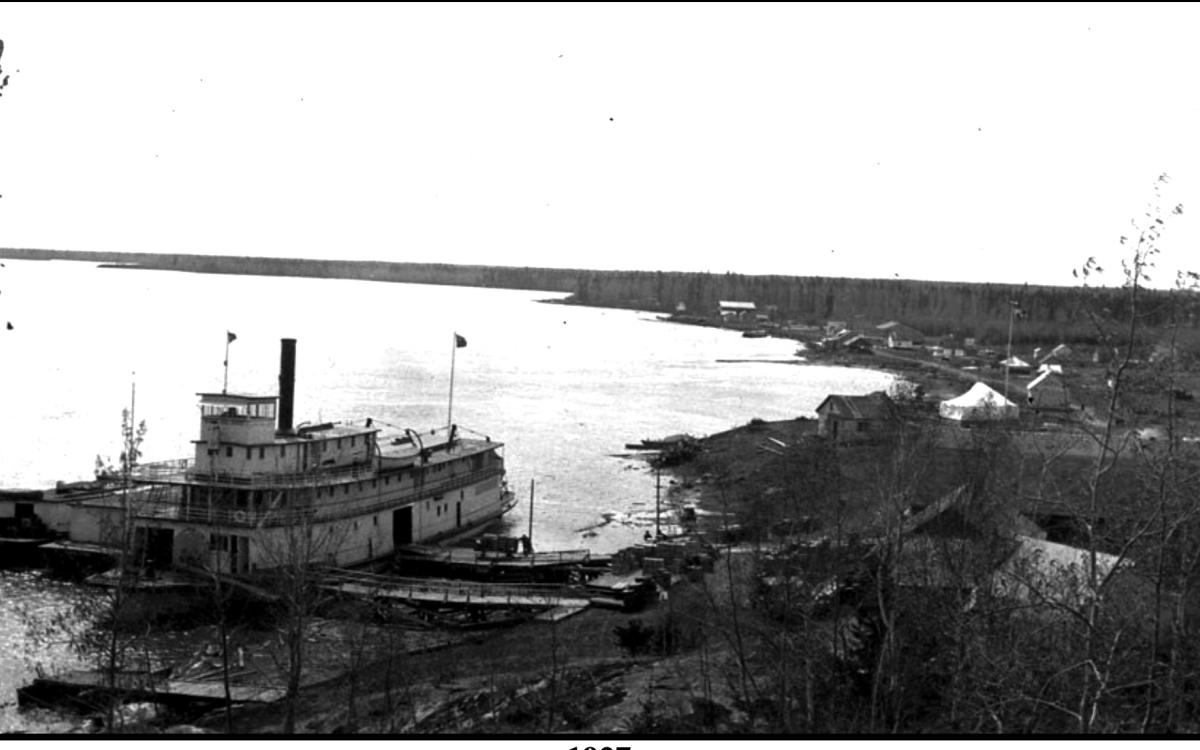

Today, Fort Fitzgerald is little more than a dot on the map. The most recent municipal census puts the population at six residents. In the 1920s, however, it was home to hundreds and had large warehouses full of trade goods and furs, an RCMP barracks, a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, the trading posts of rival fur-trading firms and a very busy waterfront.

Jean’s first impression of the community that would be her home for the next few years, and maybe longer, was not positive. When she stepped off the boat, all she saw was a “squalid trading post” with a “long, muddy waterfront littered with up-rooted trees, broken scows, rotting canoes and other rubbish.”

It took a few weeks for Jean to realize the rubbish on the waterfront was only a minor problem. Fort Fitzgerald was not a happy place. The community was split down the middle with most residents divided into two feuding camps, one centred on the RCMP and the other on the Hudson’s Bay Company.

When introduced to the head of the RCMP, a man who appears in the records only as Inspector Percival, and his wife, Constance, Jean took an instant dislike to the couple. She had heard that “the Inspector reigned in arrogant and lofty languor… deeming the rest of the small community beneath his notice.” Constance was “the very personification of the typical English governess… surrounding herself with frigid austerity.”

The feud began years earlier when the Hudson’s Bay Company claimed to own the land on which the RCMP had built its barracks. As the years went by the feud grew as the police clamped down on what they said were violations of trapping regulations.

During that first winter, Jean didn’t have much opportunity for social interaction with the other residents of Fort Fitzgerald. Philip, sick with typhoid fever, was confined to bed and required constant care. Jean’s first real glimpse of just how bad the feuding was between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the police came when Philip’s doctor ordered that he drink three glasses of fresh milk each day. The problem was the only source of fresh milk in the community was from a cow owned by the Percivals. They refused to give any to the Godsells, even when they were told that Philip might not survive if he didn’t have it.

Philip survived with the help of Fort Fitzgerald residents who smuggled milk from the Percivals’ cow to him. By next spring he was strong enough to travel with Jean on a long journey onboard the paddlewheeler SS Mackenzie River north to Aklavik. This was the North Jean had dreamed of, but her fond thoughts quickly faded on the couple’s return to Fort Fitzgerald in the fall. Someone in the community had spent the summer spreading scandalous rumours about the Godsells, and Jean now had a job to do.

It took her months, but Jean was eventually able to trace the source of these vicious rumours to the wife of one of the police constables, a woman named Bella. Since the Godsells returned to Fort Fitzgerald, Bella had been sticking close to home, so it wasn’t until one November afternoon in 1922 that Jean was able to confront her concerning these false rumours.

Their discussion—nose to nose on Fort Fitzgerald’s main waterfront street—soon escalated and, as a curious crowd gathered, fists began to fly. Jean, as she was to write nearly 35 years later, “thrashed the trembling, snivelling creature within an inch of her life and sent her crawling and moaning back to the barracks.”

When the police attempted to arrest Jean, most of the community rallied around her, congratulating her on putting Bella in her place and refusing to cooperate with the police. This was the first time in years that the people of Fort Fitzgerald had been united. The scandalous rumours about Jean and her husband came to an abrupt halt only to be replaced by stories, told and retold throughout the North, of that day in 1922 when Jean beat up Bella.